Berkeley, California

City of Berkeley | |

|---|---|

Berkeley as seen from the Claremont Canyon Regional Preserve. | |

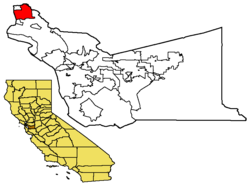

The City of Berkeley highlighted within Alameda County. | |

| Country State County | United States California Alameda |

| Incorporated | April 4, 1878 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tom Bates |

| Elevation | Formatting error: invalid input when rounding m (0 to 1,320 ft) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 102,743 |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Website | http://www.ci.berkeley.ca.us |

Berkeley is a city on the east shore of San Francisco Bay in northern California, in the United States. Its neighbors to the south are the cities of Oakland, California and Emeryville, California. To the north is the city of Albany and the unincorporated Kensington. The eastern city limits coincide with the county line (bordering on Contra Costa County) which generally follows the ridgeline of the Berkeley Hills. Berkeley is located in Alameda County.

Berkeley is the site of the University of California, Berkeley, the flagship campus of the University of California, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Lawrence Hall of Science, Space Sciences Laboratory, and Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, which are on the campus grounds. Adjacent to the University campus is the Graduate Theological Union.

History

The site of today's City of Berkeley was the territory of the Chochen/Huichin band of the Ohlone people when the first Europeans arrived. Remnants of their existence in the area include pits in various rock formations which were used to grind acorns from native oak trees, and a shellmound now mostly leveled and covered up along the shoreline of San Francisco Bay at the mouth of Strawberry Creek. Other artifacts were discovered in the 1950s in the downtown area during the remodeling of a commercial building, near the course of the same Strawberry Creek.

The first people of European ancestry (most of whom were actually of mixed ancestry and born in America) arrived with the De Anza Expedition of 1776, which is today noted by signage on U.S. Interstate 80 which runs along the San Francisco Bay shoreline of Berkeley. The De Anza Expedition resulted in the establishment of the Spanish Presidio of San Francisco at the entrance to San Francisco Bay (the "Golden Gate") which is due west of Berkeley. Among the soldiers serving at the Presidio was one Luís Peralta. For his services to the King of Spain, he was granted a vast extent of land on the east shore of San Francisco Bay (the "contra costa") for a ranch, including that portion which now comprises the City of Berkeley.

Luis Peralta named his holding "Rancho San Antonio". The primary activity of the ranch was the raising of cattle for meat and hides, but hunting and farming were also pursued. Eventually, he gave portions of his ranch to each of his four sons. Most of the portion that is now Berkeley was the domain of his son Domingo, the rest being held by his son Vicente. No artifact survives of the ranches of Domingo or Vicente, although their names have been preserved in the naming of Berkeley streets (Vicente, Domingo, and Peralta). However, the legal title to all land in the City of Berkeley remains based on the original Peralta land grant.

The Peraltas' Rancho San Antonio continued after Alta California passed from Spanish to Mexican sovereignty as a result of the Mexican War of Independence. However, the advent of U.S. sovereignty as a result of the Mexican War, and especially, the Gold Rush, saw the Peralta's lands quickly encroached on by squatters and diminished by dubious legal proceedings. The lands of the brothers Domingo and Vicente were quickly reduced to reservations close to their respective ranch homes. The rest of the land was surveyed and parceled out to various American claimants.

Politically, the area that became Berkeley was initially part of a vast Contra Costa County, but shortly, Alameda County was created by division of Contra Costa County.

The area of Berkeley was at this period mostly a mix of open land, farms and ranches, with a small though busy wharf by the Bay. It was not yet "Berkeley", but merely the northern part of the "Oakland Township" subdivision of Alameda County.

In 1866, the private College of California located in the city of Oakland sought out a new site. They picked a location north of Oakland along the foot of the Contra Costa Hills (later called the Berkeley Hills) astride Strawberry Creek, and at about an elevation of 500 feet above the Bay, commanding a fantastic view of the Bay Area and the Pacific Ocean through the Golden Gate.

According to the Centennial Record of the University of California, "In 1866…at Founders' Rock, a group of College of California men were watching two ships standing out to sea through the Golden Gate. One of them, Frederick Billings, was reminded of the lines of Bishop Berkeley, 'westward the course of empire takes its way,' and suggested that the town and college site be named for the eighteenth-century British philosopher and poet."

The College of California's "College Homestead Association" laid out a plat and street grid which became the basis of Berkeley's modern street plan. Their plans to raise funds though fell far short of their desires, and collaboration was then begun with the State of California, culminating in 1868 with the creation of the public University of California.

As construction began on the new site, more residences began to be constructed in the vicinity of the new campus. At the same time, a settlement of residences, saloons, and various industries had also been growing up around the wharf on the bayshore called "Ocean View".

By the 1870s the Transcontinental Railroad had reached its terminus in Oakland. In 1876, a branch line of the Central Pacific Railroad was laid from Oakland into what is now downtown Berkeley. That same year, the main line of the transcontinental railroad into Oakland was re-routed, putting the right-of-way along the bayshore through Ocean View.

In 1878, the people of Ocean View and the area around the University campus, together with the local farmers incorporated themselves as the Town of Berkeley. The first elected trustees of the Town were the slate of Dennis Kearney's Workingman's Party who were particularly favored in the working class area of the former Ocean View, now called "West Berkeley". The area near the University became known as "East Berkeley".

The modern age came quickly to Berkeley, no doubt due to the influence of the University. Electric lights were in use by 1888. The telephone had already come to town. Electric streetcars soon replaced the horsecar. A silent film of one of these early streetcars in Berkeley can be seen at the Library of Congress website: "A Trip To Berkeley, California"

Berkeley's slow growth ended abruptly with the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. The town and other parts of the East Bay somehow managed to escape even moderate damage from the massive temblor, and hundreds if not thousands of refugees flowed across the Bay. In 1909, the citizens of Berkeley adopted a new charter, and the Town of Berkeley became the City of Berkeley. Rapid growth continued right up to the Crash of 1929. The Great Depression hit Berkeley hard, but not as hard as many other places in the U.S. thanks in part to the University.

The next big growth occurred with the advent of World War II when large numbers of people moved into the Bay Area to work in the many war industries. One who moved out, but played a big role in the outcome of the War was U.C. Professor and Berkeley resident J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The postwar years saw moderate growth of the City, but events on the U.C. campus began to build up to the recognizable activism of the sixties. In the 1950s, McCarthyism induced the University to demand a loyalty oath from its professors, many of whom refused to sign any such oath on the principle of freedom of thought. In 1960, a U.S. House committee (HUAC) came to San Francisco to investigate the influence of communists in the Bay Area. Their inquisition was met by protestors, including many from the University. Meanwhile, a number of U.C. students became active in support of the Civil Rights Movement. Finally, the University in 1964 provoked a massive student protest by banning the distribution of political literature on campus. This protest became known as the Free Speech Movement. As the Vietnam War rapidly escalated in the ensuing years, so did student activism at the University.

Perhaps the crowning event of the Berkeley Sixties scene was the conflict over a parcel of University property south of the contiguous campus site which came to be called "People's Park".

The battle over the disposition of People's Park resulted in a month-long occupation of Berkeley by the National Guard on orders of then-Governor Ronald Reagan. In the end, the park remained undeveloped, and remains so today. A spin-off "People's Park Annex" was established at the same time by activist citizens of Berkeley on a strip of land above the Bay Area Rapid Transit subway construction along Hearst Avenue northwest of the U.C. campus. The land had also been intended for development, but was peacefully turned over to the City and is now Ohlone Park.

The era of large public protest in Berkeley waned considerably with the end of the Vietnam War in 1974. But activist politics continue. One person who rose in prominence during the late sixties and into the seventies was Ron Dellums, nephew of C.L. Dellums, an African American labor leader. He first served on the Berkeley City Council, and later became a Congressman for the district which includes Berkeley.

The seventies saw a decline in the population of Berkeley. People left for various reasons, some moving to the suburbs, some because of the rising cost of living throughout the Bay Area, and others because of the decline and disappearance of many industries in West Berkeley.

The period from the 1980s right up to the present has been marked by a continuation of rising costs, particularly with respect to housing, especially since the mid-1990s. In 2005–2006, sales of homes appear to finally be slowing, but the price of an average home is still among the highest in the nation.

Although many think of the 1960s as the heyday of Liberalism in Berkeley, it remains one of the most overwhelmingly liberal cities in the United States, with its 2004 presidential vote going more than 90% for John Kerry (54,419 votes) versus only 6.7% for George W. Bush (4,010 votes).

Population by decade:

- 1890 — 5,101

- 1900 — 13,214

- 1910 — 40,434

- 1920 — 56,036

- 1930 — 82,109

- 1940 — 85,547

- 1950 — 113,805

- 1960 — 111,268

- 1970 — 116,716

- 1980 — 103,328

- 1990 — 102,724

- 2000 — 102,743

Geography

Berkeley is located at 37°52′18″N 122°16′29″W / 37.87167°N 122.27472°WInvalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function (37.871775, -122.274603)Template:GR.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 17.7 mi² (45.9 km²). 10.5 mi² (27.1 km²) of it is land and 7.2 mi² (18.8 km²) of it (40.94%) is water. most of it the adjoining San Francisco Bay.

Berkeley borders the cities of Albany, Oakland, and Emeryville and unincorporated Contra Costa County including Kensington as well as San Francisco Bay.

Geology

Most of Berkeley lies on a rolling sedimentary plain, rising gently from sea level to the base of the Berkeley Hills. From there, the land rises dramatically. The highest peak along the ridgeline above Berkeley is Grizzly Peak, elevation 1,754 feet (535 m). A number of small creeks run from the hills to the Bay through Berkeley: Codornices, Schoolhouse, Marin and Strawberry are the principal streams. Most of these are largely culverted once they reach the plain west of the hills.

The Berkeley Hills are part of the Pacific Coast Ranges, and run in a northwest-southeast alignment. In Berkeley, the hills consist mainly of a soft, crumbly rock with outcroppings of harder material of old (and extinct) volcanic origin. Some of these rhyolite formations can be seen in several city parks and in the yards of a number of private residences. One such park is Indian Rock Park in the northeastern part of Berkeley near the Arlington/Marin Circle.

Berkeley is traversed by the Hayward Fault, a major branch of the San Andreas Fault to the west. No large earthquake has occurred on the Hayward Fault near Berkeley in historic times (except possibly in 1836), but seismologists warn about the geologic record of large temblors several times in the deeper past, and their current assessment is that a quake of 6.5 or greater is imminent, sometime within the next 30 years.

In 1868, a large earthquake did occur on the southern segment of the Hayward Fault in the vicinity of today's city of Hayward (hence, how the fault got its name). This quake destroyed the county seat of Alameda County then located in San Leandro and it was subsequently moved to Oakland. It was strongly felt in San Francisco, causing major damage, and waking up one Samuel Clemens (also known as Mark Twain). It was regarded as the "Great San Francisco Quake" prior to 1906. The quake produced a furrow in the ground along the faultline in Berkeley, across the grounds of the new School for the Blind which was noted by one early University of California professor. Although no significant damage was reported to what few buildings then existed in Berkeley, the 1868 quake did destroy the vulnerable adobe home of Domingo Peralta in north Berkeley.

Today, the Hayward Fault can be seen "creeping" at various locations in Berkeley, although since it cuts across the base of the hills, this creep is typically concealed by and confused with slide activity. Some of this slide activity however is itself the result of the Hayward Fault's slow movement. Springs and sharp perpendicular jogs of streams are another sign of the fault's location and movement.

One notorious segment of the Hayward Fault runs lengthwise right down the middle of Memorial Stadium at the mouth of Strawberry Canyon on the campus of the University of California. Photos and measurements show the movement of the fault through the stadium.

Climate

Berkeley has a Mediterranean climate, with dry summers and wet winters as is typical in the Mediterranean region, but with a cool modification in summer thanks to upwelling ocean currents along the California coast.

Winter is punctuated with rainstorms of varying ferocity and duration, but also produces stretches of bright sunny days and clear cold nights. It does not normally snow, though on rare occasions the hilltops get a dusting of snow.

Spring and fall are transitional and intermediate, with some rainfall and variable temperature. Summer typically brings night and morning fog, followed by sunny, warm days.

The warmest and dryest months are typically June through September, with the highest temperatures occurring in September. Mid-summer (July–August) is often a bit cooler due to the sea breezes and fog which are most strongly developed then.

In the late spring and early fall, strong offshore winds of sinking air typically develop, bringing heat and dryness to the area. In the spring, this is not usually a problem as vegetation is still moist from winter rains, but extreme dryness prevails by the fall, creating a danger of wildfires. In September 1923 a major fire swept through the Northside of Berkeley, stopping just short of downtown. On October 21 1991, gusty hot winds fanned a conflagration along the Berkeley-Oakland border, killing 25 people and injuring 150, as well as destroying 2,449 single-family dwellings and 437 apartment and condominium units. (See "East Bay Hills Firestorm").

Demographics

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 102,743 people, 44,955 households, and 18,656 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,792.5/km² (9,823.3/mi²), one of the highest in California. There were 46,875 housing units at an average density of 1,730.3/km² (4,481.8/mi²). The racial makeup of the city was 59.17% White, 13.63% Black or African American, 0.45% Native American, 16.39% Asian, 0.14% Pacific Islander, 4.64% from other races, and 5.57% from two or more races. 9.73% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 44,955 households out of which 17.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28.9% were married couples living together, 9.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 58.5% were non-families. 38.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the city the population was spread out with 14.1% under the age of 18, 21.6% from 18 to 24, 31.8% from 25 to 44, 22.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 96.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $44,485, and the median income for a family was $70,434. Males had a median income of $50,789 versus $40,623 for females. The per capita income for the city was $30,477. About 8.3% of families and 20.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.4% of those under age 18 and 7.9% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

Berkeley is served by Amtrak, AC Transit, BART (Downtown Berkeley Station, North Berkeley, and Ashby Station) and bus shuttles operated by major employers including UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The only major freeway is an approximately two-mile long stretch of the Interstate 80/Interstate 580 overlap, running along the bay shoreline. Each day there is an influx of thousands of cars into the city by commuting UC faculty, staff and students, making parking for more than a few hours an expensive proposition.

Berkeley has one of the highest rates of bicycle and pedestrian commuting in the nation. In areas around the UC campus, students can often be seen jaywalking, especially on the one-way streets near campus residence halls. Berkeley is the safest city of its size in California for pedestrians and cyclists, when considering the number of injuries per walker and cyclist, rather than per capita.

Berkeley has modified its original grid roadway structure through use of diverters and barriers, moving most traffic out of neighborhoods and onto arterial streets (visitors often find this confusing, because the diverters are not shown on all maps). Berkeley maintains a separate grid of arterial streets for bicycles, called Bicycle Boulevards, with bike lanes and lower amounts of car traffic than the major streets to which they often run parallel.

Berkeley hosts a car sharing network run by City CarShare. Rather than owning (and parking) their own cars, members share a group of cars parked nearby. Online reservation systems keep track of hours and charges. Several "pods" (points of departure where cars are kept) exist throughout the city, in several downtown locations and at the Ashby BART station in South Berkeley.

Berkeley has had recurring problems with parking meters. In 1999, over 2,400 Berkeley meters were jammed, smashed, or sawed apart[1]. Starting in 2005 and continuing into 2006, Berkeley began to phase out mechanical meters in favor of more centralized electronic meters.

Transportation past

The first commuter service to San Francisco was provided by the Central Pacific's Berkeley Branch Railroad, a standard gauge steam railroad which ran from the Oakland ferry pier (Oakland Long Wharf) to downtown Berkeley starting in 1876. This line was extended from Shattuck and University to Vine Street ("Berryman's Station") in 1878. In the 1880s, Southern Pacific assumed operations of the Berkeley Branch. In 1911, Southern Pacific electrified this line and the several others it constructed in Berkeley, creating its East Bay Electric Lines division. The huge and heavy cars specially built for these lines came to be called the "Big Red Trains". The Shattuck line was extended and connected with two other Berkeley lines (the Ninth Street Line and the California Street line) at Solano and Colusa (the "Colusa Wye"). It was at this time that the Northbrae Tunnel and the Rose Street Undercrossing were constructed, both of which still exist (the Rose Street Undercrossing is not accessible to the public, being situated between what is now two backyards). The last Red Trains ran in 1941.

The first electric rail service in Berkeley was provided by several small streetcar companies starting in the late 1800s. Most of these were eventually bought up by the Key System of "Borax" Smith who added lines and improved equipment. The Key System's streetcars were operated by its East Bay Street Railways division. Principal lines in Berkeley ran on Euclid, The Arlington, College, Telegraph, Shattuck, and Grove (today's Martin Luther King Jr. Way). The last streetcars ran in 1948.

The first electric commuter interurban-type trains to San Francisco from Berkeley were put in operation by the Key System in 1903, several years before the Southern Pacific electrified its steam commuter lines. Like the SP, Key trains ran to a pier serviced by the Key's own fleet of ferryboats which also docked at the Ferry Building in San Francisco. After the Bay Bridge was built, the Key trains ran to the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco, sharing tracks on the lower deck of the Bay Bridge with the SP's red trains and the Sacramento Northern Railroad. It was at this time that the Key trains acquired their letter designations, which were later preserved by Key's public successor, AC Transit. Today's F bus is the successor of the F train. Likewise, the E, G and the H. Before the Bridge, these lines were simply the Shattuck Avenue Line, the Claremont Line, the Westbrae Line, and the Sacramento Street Line, respectively.

After the Southern Pacific abandoned transbay service in 1941, the Key System acquired the rights to use its tracks and overhead on Shattuck north of University and through the Northbrae Tunnel to The Alameda for the F-train, and also the tracks along Monterey Avenue as far as Colusa for the H-train. The Key System trains stopped running in April of 1958.

The Northbrae Tunnel was opened to auto traffic five years later in 1963 [2].

Places

Streets

Main streets include: Shattuck Avenue, home to the downtown business district; Telegraph Avenue; University Avenue, which runs from the bayshore to the University campus; San Pablo Avenue (Highway 123); Ashby Avenue (Highway 13) which also runs from the bayshore to the hills, connecting with the Warren Freeway and Highway 24 leading to the Caldecott Tunnel; College Avenue; Martin Luther King Junior Way; Sacramento Street; Marin Avenue; and Solano Avenue. The Eastshore Freeway (I-80 & I-580) runs along Berkeley's bayshore with ramps at Ashby, University and Gilman.

Bicycle and pedestrian paths

- Ohlone Greenway

- San Francisco Bay Trail

- I-80 Bridge — opened in 2002, a green, arch-suspension bridge spanning Interstate 80, for bikes and pedestrians only, giving access from the city at the foot of Addison Street to the San Francisco Bay Trail and the Berkeley Marina.

- Berkeley's Network of Historic Pathways — Berkeley has a network of historic pathways that link the winding neighborhoods found in the hills and offer panoramic lookouts over the East Bay. A complete guide to the pathways may be found at Berkeley Path Wanderers Association

Neighborhoods

While Berkeley is a relatively small city, a number of distinct neighborhoods have developed.

Surrounding the University of California campus are the most densely populated parts of the city. West of the campus is Downtown Berkeley, the city's traditional commercial core; home of the civic center, the city's only public high school, the busiest BART station in Berkeley, as well as a major transfer point for AC Transit buses. South of the campus is the Southside neighborhood, mainly a student ghetto, where much of the university's student housing is located. The busiest stretch of Telegraph Avenue is in this neighborhood. North of the campus is the quieter Northside neighborhood, the location of the Graduate Theological Union.

Further from the university campus, the influence of the University quickly becomes less visible. Most of Berkeley's neighborhoods are primarily made up of detached houses, often with separate in-law units in the rear, although larger apartment buildings are also common in many neighborhoods. Commercial activities are concentrated along the major avenues and at important intersections. In the southeastern corner of the city is the Claremont District, home to the Claremont Hotel; and the Elmwood District, with a small shopping area on College Avenue. West of Elmwood is South Berkeley, known for its weekend flea market at the Ashby BART station. West of (and including) San Pablo Avenue is West Berkeley, the former unincorporated town of Ocean View. West Berkeley contains the remnants of Berkeley's industrial area, much of which has been replaced by retail and office uses with the decline of manufacturing in the United States. Along the shoreline of San Francisco Bay at the foot of University Avenue is the Berkeley Marina. Nearby is Berkeley's Aquatic Park, featuring an artificial linear lagoon of San Francisco Bay. North of Downtown is the North Berkeley neighborhood, which has been nicknamed the "Gourmet Ghetto" because of the concentration of well-known restaurants and other food-related businesses. Further north are Northbrae, a master-planned subdivision from the early 20th Century, and Thousand Oaks. Above these last three neighborhoods, in the northeastern part of Berkeley, is the Berkeley Hills. The neighborhoods of the Berkeley Hills such as Cragmont and La Loma Park are notable for their dramatic views, winding streets, and numerous public stairways and paths.

Points of interest

- Berkeley Repertory Theatre

- Cloyne Court Hotel, a member of the University Students' Cooperative Association

- Hearst Greek Theatre

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

- Regional Parks Botanic Garden

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of California Botanical Garden

- Berkeley Rose Garden

Other notable places include:

- The Campanile belltower (Sather Tower) in the University of California, Berkeley campus.

- Telegraph Avenue, along with People's Park, known as a center of counterculture activity during the 1960s–70s.

- Chez Panisse, the birthplace of California cuisine.

- The Claremont Resort, originally, the Claremont Hotel. (Claims a Berkeley mailing address although the property is located almost entirely with the Oakland city limits.)

- Berkeley High School (the city's only public high school), is considered a Landmark.

- The Berkeley Community Theatre, a well-known concert hall.

- 924 Gilman, an all-ages punk rock music club where Berkeley natives Operation Ivy, Pansy Division, Green Day, Rancid and AFI started out.

- The Freight and Salvage, a folk, traditional, and world music club in West Berkeley.

- The Cheese Board, a collective bakery, cheese shop, and pizzeria.

Landmarks and Historic Districts

165 buildings in Berkeley are designated as local landmarks or local structures of merit. Of these, 49 are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including:

- Berkeley Women’s City Club, now Berkeley City Club — Julia Morgan (1929–30)

- First Church of Christ, Scientist — Bernard Maybeck (1910)

- St. John’s Presbyterian Church, now Julia Morgan Center for the Arts — Julia Morgan (1908, 1910)

- William R. Thorsen House, now Sigma Phi Society Chapter House — Charles Sumner Greene & Henry Mather Greene (1908–10)

Historic Districts listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

- Berkeley Historic Civic Center District — Roughly bounded by McKinney Avenue, Addison Street, Shattuck Avenue, and Kittredge Street (99 acres, 7 buildings, 1 structure; added 1998).

- George C. Edwards Stadium — Located at intersection of Bancroft Way and Fulton Street on University of California, Berkeley campus (80 acres, 3 buildings, 4 structures, 3 objects; added 1993).

- Panoramic Hill, also known as University Terrace — Located at Panoramic Way, Canyon Road, Mosswood Road, Orchard Lane, and Arden Road (123 acres, 61 buildings, 16 structures, 1 object; added 2005).

- State Asylum for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind, also known as California Schools for the Deaf and Blind, now Clark Kerr Campus — Bounded by Dwight Way, the City line, Derby Street, and Warring Street (500 acres, 20 buildings; added 1982).

See List of Berkeley Landmarks, Structures of Merit, and Historic Districts

Mayors

City of Berkeley Mayor's Office

- Tom Bates, Mayor of Berkeley (elected 2002), former long-time California State Assemblymember, married to California State Assemblymember and former Berkeley Mayor Loni Hancock

- Past Mayors

- (Mr.) Beverly Lacy Hodghead (Republican) 1909–1911

- Jackson Stitt Wilson (Socialist) 1911–1913

- Charles D. Heywood 1913–1915

- Samuel C. Irving (Republican) 1915–1919

- Louis Bartlett (Republican) 1919–1923

- Frank D. Stringham (Republican) 1923–1927

- Michael B. Driver (Republican) 1927–1930

- Thomas E. Caldecott (Republican) 1930–1932

- Edward N. Ament (Republican) 1932–1939

- Frank S. Gaines (Republican) 1939–1943

- Fitch Robertson (Republican) 1943–1946

- Carrie Hoyt (Republican) 1947 (Jan–Apr)

- Laurance L. Cross (Republican) 1947–1955

- Claude B. Hutchinson (Republican) 1955–1963

- Wallace Johnson (Republican) 1963–1971

- Warren Widener (Democrat) 1971–1979

- Gus Newport (Berkeley Citizens Action) 1979–1986

- Loni Hancock, (Berkeley Citizens Action) 1986–1994

- Jeffrey Shattuck Leiter, 1994 (Mar–Dec)

- Shirley Dean, (Berkeley Democrat Club) 1994–2002

- Presidents, Town Board of Trustees (1878–1909)

- Abel Whitton (Workingman's Party) 1878–1881

- Samuel Heywood 1882-1884

- William H. Marston 1902–1906

Sister cities

Berkeley has declared the following sister city relationships:

- Blackfeet Nation, California, United States

- Blackfeet Nation, California, United States - Haidian District, Beijing, China

- Haidian District, Beijing, China - Jena, Thueringen, Germany

- Jena, Thueringen, Germany - Ulan-Ude, Buryatiya (Ulan-Ude), Russia

- Ulan-Ude, Buryatiya (Ulan-Ude), Russia - Yurok Tribe, California, United States

- Yurok Tribe, California, United States - Uma-Bawang, Malaysia

- Uma-Bawang, Malaysia - Sakai, Osaka, Japan

- Sakai, Osaka, Japan - San Antonio Los Ranchos, Chalatenango, El Salvador

- San Antonio Los Ranchos, Chalatenango, El Salvador - Oukasie, South Africa

- Oukasie, South Africa - Yondó, Antioquia, Colombia

- Yondó, Antioquia, Colombia - Palma Soriano, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba

- Palma Soriano, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba - Leon, Nicaragua

- Leon, Nicaragua

Notable Berkeley residents past and present

- Ben Affleck — actor

- Billie Joe Armstrong — Guitarist/Vocalist of Green Day

- Tim Armstrong — member of punk rock bands Rancid and Operation Ivy

- Les Blank — documentary filmmaker

- David Brower — environmentalist

- Michael Chabon — author

- Daniel Clowes — cartoonist

- Francis Ford Coppola — filmmaker and vintner

- Robert Crumb — cartoonist

- Robert Culp — actor

- Richard Diebenkorn — painter

- Philip K. Dick — author

- Mike Dirnt — bassist of Green Day

- Adam Duritz — singer/songwriter, Counting Crows

- Dave Eggers — writer

- Daniel Ellsberg — military analyst

- John Fogerty — singer/songwriter

- C.S. Forester — author, Horatio Hornblower series and The African Queen

- Matt Freeman — member of punk rock bands Rancid and Operation Ivy

- Terry Garthwaite — singer/songwriter and founding member of folk-rock band Joy of Cooking

- Richard Gere — actor

- Allen Ginsberg — poet

- Whoopi Goldberg — actress and comedian

- Wavy Gravy — activist and 1960s counterculture icon

- Davey Havok — singer for AFI

- Patty Hearst — newspaper heiress and kidnap victim

- Gregory Hoblit — film and television director

- Ken Hom — chef

- David Horowitz — 1960s radical turned conservative activist

- Charlie Hunter — jazz musician

- David Immerglück — guitarist, Counting Crows

- Ishi — last of the Yahi

- Candido Jacuzzi — inventor of submersible pump

- Pauline Kael — movie critic

- Theodore Kaczynski — aka the Unabomber

- Ursula K. Le Guin — author

- Marion Zimmer Bradley — author

- Jack LaLanne — health enthusiast

- Timothy Leary — LSD enthusiast

- Phil Lesh — former Grateful Dead bassist

- George Lucas — filmmaker

- Billy Martin — baseball player and manager

- Andrew Martinez — social activist

- Country Joe McDonald — Singer/Songwriter

- Roger Montgomery — urban designer, architect, Dean University of California, Berkeley

- Norman Mineta — U.S. Transportation Secretary

- Gordon Moore — co-founder of Intel

- Charles Muscatine — UC Professor, challenged loyalty oath

- Huey P. Newton — Black Panther Party

- Adm. Chester Nimitz — WWII commander of U.S. Pacific forces

- Joaquin Nin-Culmell — UC Professor (emeritis), composer, brother of Anais Nin

- Frank Norris — author of The Octopus

- Robert Oppenheimer — scientist and head of the Manhattan Project

- Lenny Pickett — SNL band leader, saxophone player

- Joshua Redman — jazz musician

- Janet Ritz — author, musician, environmental activist

- Rosalie Ritz — courtroom artist, reporter

- John Linton Roberson — underground writer/cartoonist

- Rebecca Romijn — model, actress

- Freddie Roulette — blues guitarist, lap steel

- Andy Samberg — SNL comedian

- Mario Savio — 1960s Free Speech Movement icon

- Adam Sessler — host of G4tv's Xplay

- George R. Stewart — author of the novels Earth Abides and Storm

- Edward Teller — nuclear physicist, thermonuclear weapons

- Lars Ulrich — Metallica drummer

- Alice Waters — restaurateur

- Thornton Wilder — playwright (Our Town, etc.)

- Helen Wills — tennis champion

- Pete Wilson — former governor of California

- Saul Zaentz — film producer

- Zahara Schatz — sculpter, artist

- Markos Moulitsas Zúniga — Daily Kos

See also these lists of notable people associated with the University:

- List of Nobel laureates associated with UC Berkeley

- List of UC Berkeley faculty

- List of UC Berkeley alumni

Trivia

- Due to the generally liberal to radical views of the Berkeley public, the city is sometimes mockingly referred to as the People's Republic of Berkeley (and some even deride it as "Berzerkley"). This reputation, along with its generally temperate weather, high rates of tourism, and large student population, have attracted large numers of transient people, many of whom are homeless.

- Berkeley has an element named for it: berkelium. The element was first synthesized in 1949 at what was then called the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory ("Rad Lab") of the University of California, Berkeley.

- In 1986 Berkeley officially became a Nuclear Free Zone after a local vote, disallowing the operation of nuclear reactors within city limits and preventing work from being done on nuclear weapons within its borders. This is somewhat ironic, given Berkeley's past: the UC Berkeley played a major role in the development of nuclear weapons in the Manhattan Project, and a nuclear research center, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is located in the hills above the city. Street signs posted at the city borders declaring its Nuclear Free Zone status are the most noticeable effect of the measure. The University once housed a small research reactor, which was decommissioned in the 1990s, though the University denies that this had anything to do with the Act.

- Berkeley celebrates "Indigenous People's Day" rather than Columbus Day.

- In 1989, Berkeley banned the use of polystyrene packaging for keeping McDonald's hamburgers warm. This was one of the earliest events in the plastics recycling movement in the U.S.

- Before he served as a general in the American Civil War, William Tecumseh Sherman owned tracts of land in Berkeley, although he did not reside here.

- Berkeley's police department, under its first chief August Vollmer early in the 20th century, was the first in the U.S. to require that officers have a college degree. This department developed the lie detector test, and was one of the first to use fingerprints and radios. In 1973, Berkeley's city council enacted its well-known Berkeley Marijuana Initiative. The act ordered Berkeley police to make "no arrests and issue no citations for violations of marijuana laws."

- The City of Berkeley is home to a number of well-known artists, architects, composers, writers and thinkers: Fritjof Capra, Susan Griffin, Christopher Alexander, Rita Moreno, Michael Parenti, Michael Lerner, Michael Chabon, and others. The city also has more independent publishers per capita than any other city in the country, and more bookstores per capita. Additionally, many famous bands have originated in Berkeley, including Operation Ivy and Green Day. Berkeley, being one of the birthplaces of underground and independent comics, is also noted as a haven for cartoonists, including Dan Clowes and Adrian Tomine.

- Berkeley has become known as a gourmet food center. There are a number of specialty food shops and restaurants, such as the Berkeley Bowl Marketplace, the Chez Panisse restaurant, regarded as the birthplace of California cuisine. Its proprietor, Alice Waters, has been called "the mother of American cooking." Among the shops, The Cheese Board Collective is a well-known, cooperatively-run bakery and cheese shop.

- Since the 1970s, the Bay Area Rapid Transit system (BART), a metro train system, has linked Berkeley to San Francisco and the other cities of the Bay Area. Berkeley has nevertheless maintained its own character. BART planners proposed an above-ground route through Berkeley, but Berkeley residents rejected the plan and voted for a subway instead, whose extra cost was funded by a bond issue. Consequently, BART runs entirely underground through Berkeley, but emerges to run above ground at the borders of the neighboring cities of Albany and Oakland.

- The city is also the birthplace of the nation's first community-funded radio station, KPFA, the flagship station of the Pacifica Radio network.

- Fewer people live in Berkeley today than did 55 years ago. Few other cities in the western United States can make this claim.

- Dick Leonard, the "father of modern rock climbing," and noted environmentalist David Brower, founder of Friends of the Earth, learned rock climbing and developed their mountaineering techniques at Indian Rock Park in Berkeley. Brower used this special knowledge to prepare training manuals during World War II.

- In 1966, the first Peet's Coffee opened in Berkeley, at the corner of Vine and Walnut.

External links

- Official Government Website

- City Of Berkeley, California

- Berkeley Public Library

- Berkeley Landmarks

- California State Assembly District 14

- Berkeley Daily Planet Website

- People's Park

- Homeless Youth Shelter

- Berkeley Firefighters Association

- Photos of Berkeley

- Berkeley Wiki, a local community wiki / visitor's guide