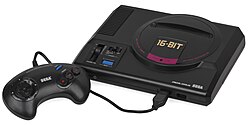

Sega Genesis

European/Australasian logo | |

Top: Original Japanese Mega Drive Bottom: Sega Genesis Model 2 Other variations are pictured under Variations below | |

| Manufacturer | Sega |

|---|---|

| Type | Video game console |

| Generation | Fourth generation |

| Units sold | Estimated from 37.4 to over 41.4 million[s 1] |

| Media | ROM cartridge |

| CPU | Motorola 68000 and Zilog Z80 |

| Online services | Sega Net Work System, Sega Channel, XBAND |

| Best-selling game | Sonic the Hedgehog (pack-in), 15 million[7] Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (pack-in), 6 million[8] Aladdin, 4 million[9] |

| Predecessor | Sega Master System |

| Successor | Sega Saturn |

The Sega Genesis is a 16-bit video game console that was released in 1988 by Sega in Japan (as the Mega Drive (メガドライブ, Mega Doraibu)), 1989 in North America, and 1990 in Europe, Australasia, and Brazil, under the name Mega Drive. In South Korea it was distributed by Samsung and was first known as the Super Gam*Boy and later as the Super Aladdin Boy. The Genesis is Sega's third console and the successor to the Sega Master System with which it has backward compatibility via a peripheral. Based on Sega's System 16 arcade board, the Genesis was the first of its generation to achieve notable market share in continental Europe and North America, where it competed against a wide range of platforms, including dedicated gaming consoles and home computer systems. Two years later, Nintendo released the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), and the competition between the two would dominate the 16-bit era of video gaming. Although sales estimates vary; the Genesis was Sega's most successful console.[sn 1]

In Japan, the Mega Drive initially did not fare well against its two main competitors, Nintendo's Famicom and NEC's PC-Engine. However, it achieved much greater success in North America (where it was rebranded as the Sega Genesis) and in Europe, capturing the majority of the market share. Contributing to its success were its library of arcade-game conversions, the success of Sonic the Hedgehog, and aggressive advertisement that positioned it as the "cool" console for mature gamers. The Genesis and Mega Drive also benefited from numerous peripherals and several network services, as well as multiple third-party variations of the console that focused on extending its functionality. Though Sega dominated the market in North America and Europe for several years, the release of the SNES posed serious competition, and the console and several of its highest-profile games gained significant legal scrutiny on matters involving reverse engineering and video game violence.

The console and its games continue to be popular among fans, collectors, video game music fans, and emulation enthusiasts. Licensed third party re-releases of the console are still being produced, and several indie game developers are producing games for it. Many games have also been re-released in compilations for newer consoles and offered for download on various online services, such as Wii Virtual Console, Xbox Live Arcade, PlayStation Network and Steam.

History

In the early 1980s, Sega Enterprises, Inc., then a subsidiary of Gulf & Western, was one of the top five arcade game manufacturers active in the United States as company revenues rose to $214 million.[21] A downturn in the arcade business starting in 1982 seriously hurt the company, however, leading Gulf & Western to sell its North American arcade manufacturing organization and the licensing rights for its arcade games to Bally Manufacturing.[22] The company retained Sega's North American R&D operation, however, as well as its Japanese subsidiary, Sega of Japan. Gulf & Western executives then turned to Sega of Japan's president, Hayao Nakayama, for advice on how to proceed. Nakayama advocated that the company leverage its hardware expertise gained through years working in the arcade industry to move into the home console market in Japan, which was in its infancy at the time.[23] Nakayama received the go ahead for this project, leading to the release of Sega's first home video game system, the SG-1000, in July 1983. The SG-1000 was not successful, however, and was replaced by the Sega Mark III within two years.[24] In the meantime, Gulf & Western began to divest itself of its non-core businesses after the death of company founder Charles Bludhorn,[25] so Nakayama and former Sega CEO David Rosen arranged a management buyout of the Japanese subsidiary in 1984 with financial backing from CSK Corporation, a prominent Japanese software company. Nakayama was then installed as CEO of the new Sega Enterprises, Ltd.[26]

In 1986, Sega redesigned the Mark III for release in North America as the Sega Master System. This was followed by a European release the next year. Although the Master System was a success in Europe, and later also Brazil, it failed to ignite much interest in the Japanese or North American markets, which, by the mid-to-late 1980s, were both dominated by Nintendo.[27][28][29] Furthermore, the release of NEC's PC-Engine tightened the window in which Sega would have to release a new console to keep from having to compete with them as well as Nintendo.[30] Since the Sega System 16 had become a success in the arcades, Nakayama decided to make its new home system utilize a similar 16-bit architecture.[31]

During development, the new console was offered to Atari Corporation, which did not have a 16-bit system. David Rosen made the proposal to Atari CEO Jack Tramiel and the president of Atari's Entertainment Electronics Division, Michael Katz. However, Tramiel decided that the deal to acquire the new console would be too expensive, instead opting to focus on the Atari ST. Without Atari's support for the console, Sega continued to develop it on its own. First announced in June 1988 in Beep!, a Japanese gaming magazine, the developing console was referred to as the "Mark V", but at Sega's discretion, the company sought a stronger title for the system. After reviewing over 300 proposals, Sega settled on "Mega Drive" as the console's name. In North America, however, the name of the console was changed to "Genesis". The reason for this change is not known, but it may have been due to a trademark dispute.[31]

Launch

Sega released the Mega Drive in Japan on October 29, 1988. The launch was overshadowed by Nintendo's release of Super Mario Bros. 3 a week earlier. Positive coverage from magazines Famitsu and Beep! helped to establish a following, but Sega only managed to ship 400,000 units in the first year. In order to increase sales, Sega released various peripherals and games, including an online banking system and answering machine called the Sega Mega Anser.[31] Despite this, the Mega Drive was unable to overtake the Famicom,[32] and remained a distant third in Japan behind Nintendo's Super Famicom and NEC's PC-Engine throughout the 16-bit era.[33]

Sega announced a North American release date for the system on January 9, 1989.[34] After not being able to complete a distribution deal with Atari, Sega was not able to meet the initial release date and US sales eventually began on August 14, 1989 in New York City and Los Angeles. The Sega Genesis was released in the rest of North America later that year.[35] The European release, as the Mega Drive, was on November 30, 1990. Following on from the European success of the Sega Master System, the Mega Drive became a very popular console in Europe. Unlike in other regions where the Famicom/NES had been the dominant platform, the Sega Master System was the most popular console in Europe at the time. Since the Mega Drive was already two years old at the release in Europe, more games were available at launch compared to the launches in other regions. The ports of arcade titles like Altered Beast, Golden Axe and Ghouls 'n Ghosts, available in stores at launch, provided a strong image of the console's power to deliver an arcade-like experience.[36]

In Brazil, the Mega Drive was released by Tec Toy in 1990,[37] only a year after the Brazilian release of the Sega Master System. Tec Toy also produced games exclusively for the Brazilian market and began a network service for the system called Sega Meganet in 1995.[38] In India, Sega entered a distribution deal with Shaw Wallace in Spring 1995, with each unit selling for INR₹18,000.[39] Sega entered the partnership in order to circumvent an 80% import tariff.[40] Samsung handled sales and distribution of the console in Korea, where it was renamed the "Super Gam*Boy" and retained the Mega Drive logo alongside the Samsung name.[41] It was later renamed as "Super Aladdin Boy".[42]

Aggressive marketing

For the North American market, former Atari Corporation Entertainment Electronics Division president and new Sega of America CEO Michael Katz instituted a two-part approach to build sales in the region. The first part involved a marketing campaign to challenge Nintendo head-on and emphasize the more arcade-like experience available on the Genesis,[43] summarized by the slogans including "Genesis does what Nintendon't".[31] Since Nintendo owned the console rights to most arcade games of the time, the second part involved creating a library of instantly-recognizable titles which used the names and likenesses of celebrities and athletes such as Pat Riley Basketball, Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf, James 'Buster' Douglas Knockout Boxing, Joe Montana Football, Tommy Lasorda Baseball, Mario Lemieux Hockey and Michael Jackson's Moonwalker.[44][30] Nonetheless, it had a hard time overcoming Nintendo's ubiquitous presence in the consumer's home.[45] Tasked by Nakayama to sell one million units within the first year, Katz and Sega of America managed only to sell 500,000 units.[31]

In mid-1990, Nakayama hired Tom Kalinske to replace Katz as CEO of Sega of America. Although Kalinske initially knew little about the video game market, he surrounded himself with industry-savvy advisors. A believer in the razor and blades business model, he developed a four-point plan: cut the price of the console; create a US-based team to develop games targeted at the American market; continue and expand the aggressive advertising campaigns; and replace the bundled game, Altered Beast, with a new title, Sonic the Hedgehog.[45] The Japanese board of directors initially disapproved of the plan[46] but all four points were approved by Nakayama, who told Kalinske, "I hired you to make the decisions for Europe and the Americas, so go ahead and do it."[31] Magazines praised Sonic as one of the greatest games yet made and Sega's console finally took off as customers who had been waiting for the SNES decided to purchase a Genesis instead.[45] Nintendo's console debuted against an established competitor, while NEC's TurboGrafx-16 failed to gain traction and NEC soon pulled out of the market.[47]

Due to the Genesis' head start, a larger library of games when compared to the SNES at its release, and a lower price point,[48] Sega was able to secure an estimated 60% of the American 16-bit console market by June 1992.[49] Sega's advertising continued to position the Genesis as the "cooler" console,[48] and at one point in its campaign, it used the term "blast processing" (the origin of which is an obscure programming trick on the console's graphics hardware[50]) to suggest that the processing capabilities of the Genesis were far greater than those of the SNES.[51] A Sony focus group found that teenage boys would not admit to owning a Super NES rather than a Genesis.[52] Even with the Genesis often outselling the Super NES at a ratio of 2:1,[53] neither console could maintain a definitive lead in market share for several years, with Nintendo's share of the 16-bit machine business dipping down from 60% at the end of 1992 to 37% at the end of 1993,[54] Sega accounting for 55% of all 16-bit hardware sales during 1994,[55] and Donkey Kong Country paving the way for the Super NES to win a handful of the waning years of the 16-bit generation.[20][18][56] According to a 2004 study of NPD sales data, the Sega Genesis was able to maintain its lead over the Super NES in the American 16-bit console market.[57]

Sonic the Hedgehog

While Sega was seeking a flagship series to compete with Nintendo's Mario series along with a character to serve as a company mascot, several character designs were submitted by its Sega AM8 research and development department. Many results came forth from their experiments with character design, including an armadillo (who later developed into Mighty the Armadillo), a dog, a Theodore Roosevelt look-alike in pajamas (who would later be the basis of Dr. Robotnik/Eggman's design), and a rabbit (who would use its extendible ears to collect objects, an aspect later incorporated in Ristar).[7][58] Eventually, Naoto Ōshima's spiky teal hedgehog, initially codenamed "Mr. Needlemouse", was chosen as the new mascot.[51]

Sonic's blue pigmentation was chosen to match Sega's cobalt blue logo, and his shoes were a concept evolved from a design inspired by Michael Jackson's boots with the addition of the color red, which was inspired by both Santa Claus and the contrast of those colors on Jackson's 1987 album Bad; his personality was based on Bill Clinton's "Get it done" attitude.[7][59][60][61] A group of fifteen people started working on the first Sonic the Hedgehog game, and renamed themselves Sonic Team.[62]

Though Katz disliked the idea of Sonic, certain that most American kids would not catch on with it,[30] Kalinske's strategy to place Sonic the Hedgehog as the pack-in title paid off.[63][36] Featuring speedy gameplay, Sonic the Hedgehog greatly increased the popularity of the Sega Genesis in North America.[51] Bundling Sonic the Hedgehog with the Sega Genesis is credited with helping Sega gain 65% of the market share against Nintendo.[7] In large part due to the popularity of this game, the Sega Genesis outsold the Super Nintendo in the United States nearly two to one during the 1991 holiday season. This success led to Sega overtaking Nintendo in January 1992 with control of 65% of the 16-bit console market, making it the first time Nintendo was not the console leader since December 1985.[64]

Trademark Security System and Sega v. Accolade

After the release of the Sega Genesis in 1989, video game publisher Accolade began exploring options to release some of their PC game titles onto the console. At the time, however, Sega had a licensing deal in place for third-party developers that increased the costs to the developer. According to Accolade co-founder Alan Miller, "One pays them between $10 and $15 per cartridge on top of the real hardware manufacturing costs, so it about doubles the cost of goods to the independent publisher."[65] In addition to this, Sega required that it would be the exclusive publisher of Accolade's games if Accolade were to be licensed, preventing Accolade from releasing its games to other systems.[66][67] To get around licensing, Accolade chose to seek an alternative way to bring their games to the Genesis by purchasing one in order to decompile the executable code of three Genesis games and use it to program their new Genesis cartridges in a way that would allow them to disable the security lockouts on the Genesis that prevented unlicensed games from being able to be played.[66][68] This was done successfully to bring Ishido: The Way of Stones to the Genesis in 1990.[69] In doing so, Accolade had also copied Sega's copyrighted game code multiple times in order to reverse engineer the software of Sega's licensed Genesis games.[67][70]

As a result of the piracy and unlicensed development issues, Sega incorporated a technical protection mechanism into a new edition of the Genesis released in 1990, referred to as the Genesis III. This new variation of the Genesis included a code known as the Trademark Security System (TMSS), which, when a game cartridge was inserted into the console, would check for the presence of the string "SEGA" at a particular point in the memory contained in the cartridge. If and only if the string was present, the console would run the game, and would briefly display the message: "Produced by or under license from Sega Enterprises, Ltd."[66] This system had a twofold effect: it added extra protection against unlicensed developers and software piracy, and it forced the Sega trademark to display when the game was powered up, making a lawsuit for trademark infringement possible if unlicensed software were to be developed.[68][70] Accolade learned of this development at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January 1991, at which Sega showed the new Genesis III and demonstrated it screening and rejecting an Ishido game cartridge.[68] With more games planned for the following year, Accolade successfully identified the TMSS file. They later added this file to the games HardBall!, Star Control, Mike Ditka Power Football, and Turrican.[68]

In response to the creation of these unlicensed games, Sega filed suit against Accolade in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California on October 31, 1991, on charges of trademark infringement and unfair competition, in violation of the Lanham Act. Copyright infringement, a violation of the Copyright Act of 1976, was added a month later to the list of charges. In response, Accolade filed a counterclaim for falsifying the source of its games by displaying the Sega trademark when the game was powered up.[67][71] Although the district court initially ruled for Sega and issued an injunction preventing Accolade from continuing to reverse engineer the Genesis, Accolade appealed the verdict to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.[72]

On August 28, 1992, the Ninth Circuit overturned the district court's verdict and ruled that Accolade's decompilation of the Sega software constituted fair use.[73] The court's written opinion followed on October 20 and noted that the use of the software was non-exploitative, despite being commercial,[66][74] and that the trademark infringement, being required by the TMSS for a Genesis game to run on the system, was inadvertently triggered by a fair use act and the fault of Sega for causing false labeling.[66] As a result of the verdict being overturned, the costs of the appeal were assessed to Sega;[66] however, the injunction remained in force because Sega petitioned the appeals court to rehear the case,[75] which was denied on January 26, 1993.[76]

Sega and Accolade ultimately settled on April 30, 1993. As a part of this settlement, Accolade became an official licensee of Sega, and later developed and released Barkley Shut Up and Jam! while under license.[77] The terms of the licensing, including whether or not any special arrangements or discounts were made to Accolade, were not released to the public.[78] The financial terms of the settlement were also not disclosed, although both companies agreed to pay their own legal costs.[79]

Videogame Rating Council and Congressional hearings on video game violence

In 1993, American media began to focus on the mature content of some video games, with games like Night Trap for the Sega CD, an add-on for the Genesis, receiving unprecedented scrutiny. Issues about Night Trap were also brought up in the United Kingdom, with former Sega of Europe development director Mike Brogan noting that "Night Trap got Sega an awful lot of publicity.... Questions were even raised in the UK Parliament about its suitability. This came at a time when Sega was capitalizing on its image as an edgy company with attitude, and this only served to reinforce that image."[32] However, the most controversial title of the year by far was Midway's Mortal Kombat, ported to the Genesis and SNES by Acclaim. In response to public outcry over the game's graphic violence, Nintendo decided to replace the blood in the game with "sweat" and the arcade's gruesome "fatalities" with less violent finishing moves.[80]

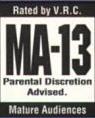

Sega took a different approach, instituting America's first video game ratings system, the Videogame Rating Council (VRC), for all of its current systems. Ratings ranged from the family friendly GA rating to the adults-only ratings of MA-13, and MA-17.[80] This allowed Sega to release its version of Mortal Kombat with a relatively low MA-13 rating, appearing to have removed all of the blood and sweat effects and toning down the finishing moves even more than in the SNES version. However, all of the arcade's blood and uncensored finishing moves could be enabled by entering a "Blood Code".[81] Meanwhile, the tamer SNES version shipped without a rating at all.[81] Despite the ratings system, or perhaps because of it, the Genesis version of Mortal Kombat was well received by gaming press, as well as fans, outselling the SNES version three to one,[80] while Nintendo was criticized for censoring the SNES version of the game.[81] However, executive vice president of Nintendo of America Howard Lincoln was quick to point out at the hearings that Night Trap had no such rating, saying to Senator Joseph Lieberman, "Furthermore, I can’t let you sit here and buy this nonsense that this Sega Night Trap game was somehow only meant for adults. The fact of the matter is this is a copy of the packaging. There was no rating on this game at all when the game was introduced. Small children bought this at Toys “R” Us, and he knows that as well as I do. When they started getting heat about this game, then they adopted the rating system and put ratings on it."[80] In response, Sega of America vice president Bill White responded by showing a videotape of violent video games on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and stressed the importance of rating video games. At the end of the hearing, Lieberman called for another hearing in February of 1994 to check progress toward a rating system for video game violence.[80]

As a result of the Congressional hearings, Night Trap started to generate more sales and also released ports to the PC and Sega 32X. According to Digital Pictures founder Tom Zito, "You know, I sold 50,000 units of Night Trap a week after those hearings."[80] Despite the increased sales, Sega decided to recall Night Trap and re-release it with revisions in 1994, due to the Congressional hearings.[82] After the close of these hearings, video game manufacturers came together in 1994 to establish the rating system called for by Lieberman. Initially, Sega proposed the universal adoption of their own system, the Videogame Rating Council. Objections from Nintendo and others, however, prevented the use of the Sega rating system, so Sega took a role in the creation of a new system along with other developers. This would materialize in the form of the Entertainment Software Ratings Board, an independent organization which received praise from Lieberman.[80] With these rating systems in place, Nintendo decided its censorship policies were no longer needed. Consequently, the SNES port of Mortal Kombat II was released uncensored.[81]

32-bit era and beyond

In order to expand the lifetime of the Genesis, Sega released two add-ons to increase the capabilities of the system: a CD-based peripheral known as the Sega CD (Sega Mega-CD in all regions except North America), as well as a 32-bit peripheral known as the Sega 32X.[63] By the end of 1995, Sega was supporting five different consoles: Saturn, Genesis/Mega Drive, Game Gear, Pico, and the Master System, as well as the Sega CD and Sega 32X add-ons. In Japan the Mega Drive had never been successful and the Saturn was beating Sony's PlayStation, so Sega Enterprises CEO Hayao Nakayama decided to force Sega of America to focus on the Saturn, executing a surprise early launch of the Saturn in early summer of 1995. While this made perfect sense for the Japanese market, it was disastrous in North America: the market for Genesis games was much larger than for the Saturn but Sega was left without the inventory or software to meet demand. In comparison, Nintendo concentrated on the 16-bit market, and as a result, Nintendo took in 42 percent of the video game market dollar share despite a continued reliance on the SNES and no new hardware launches.[83] While Sega was still able to capture 43 percent of the dollar share of the US video game market as a whole,[18] Nakayama's decision undercut the Sega of America executives. CEO Tom Kalinske, who oversaw the rise of the Genesis in 1991, grew uninterested in the business and resigned in mid-1996.[84]

In 1998, Sega licensed the Genesis to Majesco in North America so that it could re-release the console. Majesco began re-selling millions of formerly unsold cartridges at a budget price together with 150,000 units of the second model of the Genesis,[20] until it later released the Sega Genesis 3.[85]

Technical specifications

The main microprocessor of the Genesis is a 16/32-bit Motorola 68000 CPU. The console also includes a Zilog Z80 sub-processor, which controls the sound chips and provides backwards compatibility with the Master System. The system contains 72kB of RAM, as well as 64kB of video RAM, and can display up to 32 colors at once from a palette of 512. The system's games are in ROM cartridge format and are inserted in the top.[86]

The system produces sound by way of an FM synthesizer and a Texas Instruments SN76489 Programmable sound generator, used to play short PCM audio clips. The Z80 processor controls both sound chips directly. The first version of the Japanese Mega Drive contained a Yamaha YM2612 FM synthesis chip and a separate YM7101 to process video; these two chips were integrated into a single custom chip for the North American Genesis and in later versions of the console worldwide.[86]

The back of the Model 1 console provides a radio frequency output port (designed for use with antenna and cable systems) and a specialized A/V Out port, both of which provide video and audio output. Both of these outputs produce monophonic sound, while a headphone jack on the front of the console produces stereo sound.[87] On the Model 2, the custom A/V connector and headphone jack are replaced by standard RCA connectors on the back for composite video and stereo sound.[88] Some Model 1 consoles also have a 9-pin extension port, though this was removed in later production runs and is absent entirely in the Model 2. An edge connector on the bottom-right of the console allows it to be connected to a peripheral.

Peripherals

The standard Genesis controller features a rounded shape, a directional pad, three main buttons and a "start" button. Sega later released a six-button version in 1993; this pad is slightly smaller and features three additional face buttons, similar to the design of buttons on arcade fighting games. In addition, Sega also released the Remote Arcade System, a set of wireless controllers, in Europe.[89]

The Genesis is also backwards compatible with the Master System. The first peripheral released for the system, the Power Base Converter, allows Master System games to be played on the console.[90] A second model, the Master System Converter 2, was released only in Europe for use with the Mega Drive II.[89]

A number of other peripherals for the console were released that add extra functionality. The Menacer Light Gun, an infrared light gun, was a wireless peripheral used with the Menacer 6-game cartridge.[90] Other third parties also created light gun peripherals for the Genesis, such as the American Laser Games Pistol, as well as the Konami Justifier. Released for art games, the Sega Mega Mouse featured three buttons and was only able to be used for a few games, such as Eye of the Beholder. A foam-covered bat called the BatterUP and the TeeVGolf golf club were released for both the Genesis and SNES.[89]

In 1993, Sega released the Sega Activator, an octagonal device that lies flat on the floor and translates the player's physical movements into game inputs.[89] Several high-profile games, including Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter II: Special Champion Edition, were adapted to support the peripheral. However, the device was a commercial failure, due mainly to its unreliability (consumers dismissed it as "unwieldy and inaccurate") and its high price point.[89][91] IGN editor Craig Harris ranked the Sega Activator the third worst video game controller ever made.[92]

Both Electronic Arts (EA) and Sega released multitaps for the system to allow more than the standard two players to play at once. Initially, EA's version, the 4 Way Play, and Sega's adapter, the Team Player, only supported each publisher's own titles. Later games were created to work on both adapters.[89] Codemasters also developed the J-Cart system, providing two extra ports with no extra hardware, although the technology came late in the console's life and was only featured on a few games.[93]

Network services

In its first foray into online gaming, Sega created the Sega Net Work System, which debuted in Japan on November 3, 1990. Operating through a cartridge and a peripheral called the "MegaModem", this system allowed Mega Drive players to play seventeen games online. (A North American version of this system, dubbed "Tele-Genesis", was announced but never released.[94]) Another phone-based system, the Mega Anser, turned the Japanese Mega Drive into an online banking terminal.[31]

In the United States in 1993, Sega started the Sega Channel, a game distribution system utilizing cable television services Time Warner Cable and TCI. Using a special peripheral, Genesis players could download a title from a library of fifty each month, as well as demos for upcoming games. Games were downloaded to the console's internal memory and were deleted when the console was powered off. The Sega Channel reached 250,000 subscribers at its peak and ran until July 31, 1998, well past the release of the Saturn.[94]

In an effort to compete with Sega, third-party developer Catapult Entertainment created the XBAND, a peripheral which allowed Genesis players to engage in online competitive gaming. Utilizing telephone services to share data, XBAND was initially offered in five U.S. cities in November 1994. The following year, the service was extended to the SNES, and Catapult teamed up with Blockbuster Video to market the service. However, as interest in the service waned, XBAND was discontinued in April 1997.[95]

Game library

The Genesis and Mega Drive library did not initially start out at a substantial size, but eventually contained games that appealed to all types of players. The initial pack-in title was Altered Beast, which was later replaced with Sonic the Hedgehog after Kalinske proposed the change to Nakayama.[31] Sonic the Hedgehog and its sequel, Sonic the Hedgehog 2, would become the Genesis' top sellers, followed by Aladdin.[11] During development for the console, Sega of Japan was focused on developing action games, while Sega of America was tasked with developing sports games. A large part of the appeal of the Genesis library was the arcade-based experienced of their games, as well as more difficult games such as Ecco the Dolphin and sports games such as Joe Montana Football.[31]

Because of the technical limitations the Genesis had when compared to its chief competitor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, developers had to place more effort into Genesis titles in order to develop higher quality results. Notably compared to its competition as well, Sega advertised to a more adult audience by hosting more mature games, including the uncensored version of Mortal Kombat. Also making software development for the Genesis tough were Nintendo's policies, forcing third-party developers to sign agreements not to develop for any systems other than those made by Nintendo. However, such policies also brought developers to the Genesis, including Namco and Electronic Arts.[31] Ultimately, however, the number of bestselling games for the Super Nintendo far outclassed the Genesis, with several SNES games selling more than four million units each.[11]

Sega Virtua Processor

In order to produce more visually appealing graphics, companies began adding special processing chips to their game cartridges to effectively increase the console's capabilities. On the SNES, these included DSP chips and RISC processors, which allowed the console to produce faster and more accurate pseudo-3D graphics. In particular, the Super FX chip was designed to offload complex rendering tasks from the main CPU, enabling it to produce visual effects that it couldn't produce on its own. The chip was first used in Star Fox, which rendered 3D polygons in real time, and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island demonstrated the chip's ability to rotate, scale and stretch individual sprites and manipulate large areas of the screen.

As these enhancements became more commonplace on the SNES, the stock of existing Genesis games began to look outdated in comparison. Sega quickly began work on an enhancement chip to compete with the Super FX, resulting in the Sega Virtua Processor. This chip enabled the Genesis to render polygons in real time and provided an "Axis Transformation" unit that handled scaling and rotation. Virtua Racing, the only game released with this chip, ran at a significantly higher and more stable frame rate than similar games on the SNES. However, the chip was expensive to produce and increased the cost of the games that used it. At US$100, Virtua Racing was the most expensive Genesis cartridge ever produced. Two other games, Virtua Fighter and Daytona USA, were planned for the SVP chip, but were instead moved into the Saturn's launch line-up.[96]

Add-ons

In addition to accessories such as the Power Base Converter, the Sega Genesis also supported two add-ons that each supported their own game libraries. These add-ons were the Sega CD (known as the Mega-CD in all regions except for North America), a compact disc-based peripheral that played its own library of games in CD-ROM format;[97] and the Sega 32X, a 32-bit peripheral which utilized ROM cartridges as a format and served as a pass-through for Genesis games.[98] Both add-ons were officially discontinued in 1996.[97][98]

Sega CD

In 1991, compact discs had already made significant headway as a source of storage media for music and video games. PCs had started to make use of this technology, as did video game companies. NEC had been the first to utilize CD technology in a game console with the release of the TurboGrafx-CD add-on, and Nintendo was making plans to develop its own CD peripheral as well. Seeing the opportunity to gain an advantage over its rivals, Sega partnered with JVC to quickly develop a CD-ROM add-on for the Genesis.[99][100][101] Sega launched the Mega-CD in Japan[100] on December 1, 1991, initially retailing at JP¥49,800.[102], and in Europe in 1993.[102] The CD add-on was launched in North America on October 15, 1992, as the Sega CD, with a retail price of US$299.[100]

In addition to greatly expanding the potential size of its games, this add-on unit also upgraded the graphics and sound capabilities of the console by adding a second, more powerful processor, a larger color palette, more system memory, and hardware-based sprite rotation and scaling capabilities that made the console graphically competitive with the SNES.[100] It also provided battery-backed storage RAM to allow games to save high scores, configuration data, and game progress,[99] and an additional data storage cartridge was sold separately.

Shortly after its launch in North America, Sega began shipping the Sega CD with the pack-in game Sewer Shark, a full motion video (FMV) game developed by Digital Pictures, a company that became an important partner for Sega.[100] Touting the benefits of the CD's comparatively vast storage space, Sega and its third-party developers produced a number of games for the add-on that utilized digital video in their gameplay or as bonus content, as well as re-releasing several cartridge-based games with high-fidelity audio tracks.[99][97]

In 1993, Sega released the Sega CD 2, a smaller and lighter version of the add-on designed for the Genesis II, at a reduced price compared to the original.[97] A limited number of games were also later developed that utilized both the Sega CD and the Sega 32X add-ons, the latter of which was released in November 1994.[103]

Despite the great promise of this new add-on, sales of the Mega CD fell well below expectations during its first year in Japan, selling only 100,000 units. While many consumers blamed the add-on's high launch price, the add-on also suffered from a tiny software library, with only two titles being available at launch. This was due in part to Sega taking a long time to make its software development kit available to third-party developers.[102] Sales of the add-on were more successful in North America and Europe, though the novelty of FMV and CD-enhanced games quickly wore off as many of the system's later games were met with lukewarm or negative reviews. Finally, in 1995, Sega announced a shift in focus to its new console, the Saturn, and discontinued all advertising for Genesis hardware, including the Sega CD. The add-on itself was officially discontinued in 1996[97], and final sales estimates vary between 1.5 million[103] and 6 million units worldwide,[99][104] including one estimate of 2.7 million units.[6]

Sega 32X

Despite the success of the Sega Genesis, in 1994 the console was starting to lag in its capabilities when compared to its main rival, the SNES, and its newer games, Donkey Kong Country and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island. With the release of the Sega Saturn due for 1995, Sega began to develop a stop-gap solution that would bridge the gap between the Genesis and the Saturn, and would serve as a less expensive entry into the 32-bit era.[105]

Initially, the 32X began as "Project Jupiter", an entirely new independent console concept being developed by Sega of Japan. Project Jupiter was initially slated to be a new version of the Genesis, with an upgraded color palette and a lower cost than the upcoming Saturn. However, the concept did not go over well with executives at Sega of America. When presented with a demonstration of Project Jupiter, Sega of America research and development head Joe Miller said, "Oh, that's just a horrible idea. If all you're going to do is enhance the system, you should make it an add-on. If it's a new system with legitimate new software, great. But if the only thing it does is double the colors..."[106] At his suggestion, Sega reformatted the 32X into a peripheral for the existing Genesis, which became Project Mars, and expanded its power with two 32-bit processors. Although the new unit was a stronger console than was originally proposed, it was not compatible with Saturn games.[106] This was justified by Sega's statement that both platforms would run at the same time, and that the 32X would be aimed at players who could not afford the more expensive Saturn.[98]

The 32X was released in November 1994, in time for the holiday season that year. Demand among retailers was high, and Sega could not keep up orders for the system.[106] Over 1,000,000 orders had been placed for 32X units, but Sega had only managed to ship 600,000 units by January 1995.[98] Launching at about the same price as a Genesis console, the price of the 32X was less than half of what the Saturn's price would be at launch.[105] Despite the lower price console's positioning as an inexpensive entry into 32-bit gaming, Sega had a difficult time convincing third-party developers to create games for the new system. After an early run on the peripheral, news soon spread to the public of the upcoming release of the Sega Saturn, which would not support the 32X's games. This, in turn, caused developers to further shy away from the console and created doubt about the library for the 32X, despite assurances from Sega that there would be a large amount of games developed for the system. In early 1996, Sega finally conceded that they had promised too much out of the 32X and decided to stop producing the system in order to focus on the Saturn.[98] Prices for the 32X dropped to $99, then were ultimately cleared out of stores at $19.95.[106]

Variations

The Sega Genesis and Mega Drive have received many licensed variations. In addition to models made by Sega, several alternate models were made by other companies, such as Majesco, AtGames, JVC, Pioneer Corporation, Amstrad, and Aiwa. Furthermore, a number of bootleg clones were also created during its lifespan.[31]

First-party models

|

|

|

|

In 1993, Sega introduced a smaller, lighter version of the console[86], naming it the Genesis II in North America and the Mega Drive II everywhere else. This version removed the headphone jack in the front, replaced the A/V-out connector on the back with standard RCA outputs for video and stereo sound, and provided a simpler, less expensive mainboard that required less power.[107] This model also contained a number of cosmetic changes and included an upgraded memory controller that fixed a known bug, breaking a small number of games that worked on the original version.[citation needed]

Sega also released a combined, semi-portable Genesis/Sega CD unit called the Sega Genesis CDX (Sega Multi-Mega in Japan and Europe). This unit retailed at a lower price than the individual Genesis and Sega CD units put together, but was incompatible with some games and could not work with the Sega 32X due to overheating and electrical shock issues. The CDX featured a small LCD screen that, when the unit was used to play audio CDs, displayed the current track being played.[108]

Late in the 16-bit era, Sega released a handheld version of the console called the Sega Nomad (Genesis Nomad in North America), which was based on the Mega Jet, a Mega Drive portable unit used on airplane flights in Japan. It served as the successor to the Game Gear and operated on 6 AA batteries, displaying its graphics on a 3.25-inch (8.25-mm) LCD screen. The Nomad supported the entire Genesis/Mega Drive library at launch, but could not be used with the Sega 32X, the Sega CD, or the Power Base Converter.[109]

Exclusive to the Japanese market was the TeraDrive, a Mega Drive combined with a computer. Sega also produced three arcade system boards based on the Mega Drive: the System C-2, the MegaTech, and the MegaPlay, which supported approximately 80 games combined.[31]

Third-party models

|

| |

Working with Sega of Japan, JVC released the Wondermega on April 1, 1992, in Japan. The system was later redesigned by JVC and released as the X'Eye in North America in September of 1994. Designed by JVC to be a Genesis and Sega CD combination with high quality audio, the Wondermega's high price kept it out of the hands of average consumers.[110] The same was true of the Pioneer LaserActive, which was also an add-on that required an attachment developed by Sega, known as the Mega-LD pack, in order to play Genesis and Sega CD games. Though the LaserActive was lined up to compete with the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, the combined price of the system and the Mega-LD pack made it a prohibitively expensive option for Sega CD players.[111] Aiwa also released the CSD-GM1, a combination Genesis/Sega CD unit built into a boombox. Several companies added the Mega Drive to personal computers, mimicking the design of Sega's TeraDrive. These included the MSX models AX-330 and AX-990, distributed in Kuwait and Yemen, and the Amstrad Mega PC, distributed in Europe and Australia.[31]

After the Genesis was discontinued, Majesco Entertainment released the Genesis 3 as a budget version of the console in 1998.[112] In 2009, AtGames began producing two new variations: the Firecore, which could play original Genesis cartridges as well as preloaded games, and a handheld console preloaded with 20 Genesis games.[113] Numerous companies have also released various compilations of Genesis and Mega Drive games in "plug-and-play" packages resembling the system's iconic controller.

Legacy and revival

The Sega Genesis and Mega Drive has often been considered among the best video game consoles ever produced. In 2009, IGN named the Sega Genesis the fifth best video game console, citing its edge in sports games, the better home version of Mortal Kombat, and stating "what some consider to be the greatest controller ever created: the six button".[114] In 2007, GameTrailers named the Sega Genesis as the sixth best console of all time in their list of top ten consoles that "left their mark on the history of gaming", noting its great games, a solid controller, and the "glory days" of Sonic The Hedgehog.[115] In January 2008 technology columnist Don Reisinger proclaimed that the Sega Genesis "created the industry's best console war to date", citing Sonic The Hedgehog, superior sports games, and backwards compatibility with the Sega Master System.[116] GamingExcellence also gave the Sega Genesis sixth place in 2008, declaring "one can truly see the Genesis for the gaming milestone it was".[117] At the same time, GameDaily rated it ninth of ten for its memorable games.[118]

Re-releases and emulation

A number of Genesis and Mega Drive emulators have been produced, including GenEM, KGen, Genecyst, VGen, St0rm,[119] and Gens.[120] The GameTap subscription gaming service included a Mega Drive emulator and had several dozen licensed Mega Drive games in its catalog.[121] The Console Classix subscription gaming service also includes an emulator and has several hundred Mega Drive games in its catalog.[122]

A number of Mega Drive games have been released on compilation discs. These include Sonic Mega Collection and Sonic Gems Collection for PS2, Xbox and Nintendo GameCube; Sega Genesis Collection for PS2 and PSP and most recently Sonic's Ultimate Genesis Collection (known as the Sega Mega Drive Ultimate Collection in PAL territories) for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360.[123][124]

During his keynote speech at the 2006 Game Developers Conference, Nintendo president Satoru Iwata announced that Sega was going to make a number of Genesis/Mega Drive titles available to download on the Wii's Virtual Console.[125] These games are now available along with other systems' titles under the Wii's Virtual Console.[125] There are also select Mega Drive titles available on the Xbox 360 such as Sonic the Hedgehog and Sonic 2.[126]

Later new releases

On May 22, 2006, North American company Super Fighter Team released Beggar Prince, a game translated from a 1996 Chinese original.[127] It was released worldwide and was the first commercial Genesis game release in North America since 1998.[128] Super Fighter Team would later go on to release two more games for the system, Legend of Wukong and Star Odyssey[128] In December 2010, WaterMelon, an American company, released Pier Solar and the Great Architects, the first commercial role-playing video game specifically developed for the console since 1996[129] and also the biggest 16-bit game ever produced at 64Mb.[130] Pier Solar is also as the only cartridge based game to optionally utilize the Sega CD with a special enhanced soundtrack and sound effects disc.[131]

In Brazil the Mega Drive never ceased production, though Tec Toy's current models emulate the original hardware. On December 5, 2007, Tec Toy released a portable version of Mega Drive with twenty built-in games.[132] Another released version of the console, called "Mega Drive Guitar Idol", comes with two six-button joypads and a guitar controller with five fret buttons. The Guitar Idol game contains a mix of Brazilian and international songs. The console has 87 built-in games, including some new ones from Electronic Arts, originally cellphone games: FIFA 2008, Need for Speed Pro Street, The Sims 2 and Sim City.[133]

In 2009 Chinese company AtGames produced a new Mega Drive-compatible console, the Firecore.[113] It features a top-loading cartridge slot and includes two controllers similar to the six-button controller for the original Mega Drive. The console has 15 games built-in, and is region-free, allowing cartridge games to run regardless of their region of origin.[134] ATGames also produces a handheld version of the console.[135] Both machines have been released in Europe by distributing company Blaze Europe.[134]

See also

- List of Sega Mega Drive games

- List of Japanese Sega Mega Drive games

- List of Sega Mega-CD games

- List of Sega 32X games

Sales numbers

- ^ Worldwide sales

1st party: over 35.4 million[sn 1]

3rd party: 4−5 million[sn 2][sn 3]

Sega Nomad: 1 million[3]

Regional sales

North America: over 22.4−23.4 million (over 20.4 million 1st party[sn 1] + 1−2 million 3rd party[sn 2] + 1 million Sega Nomad[3])

Brazil: 3 million[sn 3]

Japan: 3.58 million[4]

Europe: 8 million[5]

Other: 3.42 million[6] (Left over from initial 29 million,[sn 1] may or may not include overlap with Tec Toy's pre 1995 sales)

Total: 37.4 to over 41.4 million

Sales notes

- ^ a b c d Many sources agree that 29 million units were sold worldwide, with 14 million of those in North America.[10][11] However, those statistics outlining the console's performance in the marketplace were originally released in 1995 before its production and sales officially ended.[6]

There is a detailed history of Sega's first party North American sales through 1997 totaling over 20.4 million. A number confirmed by the New York Times' statement "some 20 million 16-bit Genesis consoles in the United States alone".[12]

North American sales history

1989-1990: 1.2 million[13]

1991: 1.6 million[14]

1992: 4.5 million[15]

1993: 5.5 million[16]

1994: over 4 million[17]

1995: 2.1 million[18]

1996: 1.1 million[19]

1997: 400,000[20]

Total: over 20.4 million - ^ a b Majesco sold between 1 and 2 million units of their North American only Genesis 3 by the end of 1998.[1]

- ^ a b Tec Toy has sold over 3 million units of their own Mega Drives in Brazil (as of July 30th, 2012).[2] However, it is unknown if Tec Toy's pre 1995 sales are included in the initial 29 million or not. The Mega Drive is still produced and sold by Tec Toy to this day.

References

- ^ Pettus, Sam (2004-07-07). "Genesis: A New Beginning". Sega-16. Archived from the original on 2010-1-24. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Théo Azevedo (2012-07-30). "Vinte anos depois, Master System e Mega Drive vendem 150 mil unidades por ano no Brasil" (in Portuguese). UOL. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

Base instalada: 5 milhões de Master System; 3 milhões de Mega Drive

- ^ a b Blake Snow (2007-07-30). "The 10 Worst-Selling Handhelds of All Time". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Nintendo Wii almost at 8 million sold". GameZine. 2009-04-01. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Lomas, Ed (November 1996). "Over 1 Million Saturns In Europe By March". CVG. p. 10. Retrieved 2010-010-06.

8 million potential Saturn upgraders!

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Video game market share up to the end of fiscal year 1994". Man!ac Magazine. May, 1995.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Man!ac" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Sonic the Hedgehog GameTap Retrospective Pt. 3/4. GameTap. 2009-02-17. Event occurs at 1:25. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ^ Boutros, Daniel (2006-08-04). "Sonic the Hedgehog 2". Gamasutra. p. 5. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (2006-03-28). "Interview: Dr. Stephen Clarke-Willson". Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ Polsson, Ken. "Chronology of Sega Video Games". Chronology of Video Game Systems. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

Total North American sales in its lifetime: 14 million. Total world sales: 29 million.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c Buchanan, Levi (2009-03-20). "Genesis vs. SNES: By the Numbers". IGN. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ Stephanie Strom (1998-03-14). "Sega Enterprises Pulls Its Saturn Video Console From the U.S. Market". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Hisey, Pete (1991-11-04). "New technology fans video war - 16-bit video games". Discount Store News.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Elrich, David (1992-01-24). "Nintendo and Sega face off on game market at WCES". Video Business.

Sega's 1991 sales figure of 1.6 million

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Reuters (1993-01-10). "Sega Vows 1993 Will Be The Year It Overtakes Nintendo". Buffalo News. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

Sega sold 4.5 million game sets, 16 million game software units, and some 200,000 units of its new CD-ROM accessory in 1992.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Greenstein, Jane (1994-06-17). "Sega values 16-bit blitz at $500 million". Video Business.

Sega expects Genesis hardware sales in 1994 to be the same as last year, 5.5 million units.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ "Sega threepeat as video game leader for Christmas sales; second annual victory; Sega takes No. 1 position for entire digital interactive entertainment industry". Business Wire. 1995-01-06.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b c "Game-System Sales". Newsweek. 1996-01-14. Retrieved 2011-12-02. Cite error: The named reference "sales95" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Sega tops holiday, yearly sales projections; Sega Saturn installed base reaches 1.6 million in U.S., 7 million worldwide". Business Wire. 1997-01-13.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b c "Sega farms out Genesis". Consumer Electronics. 1998-03-02. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- ^ Brandt, Richard; Gross, Neil (1994). "Sega!". Businessweek. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Bottom Line". Miami Herald – via NewsBank (subscription required) . 1983-08-27. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ Battelle, John (1993). "The Next Level: Sega's Plans for World Domination". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kohler, Chris (2009). "Playing the SG-1000, Sega's First Game Machine". Wired Magazine's online site. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "G&W Wins Cheers $1 Billion Spinoff Set". Miami Herald – via NewsBank (subscription required) . 1983-08-16. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Birth of Sega". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 343. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 303, 360. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ a b c Fahs, Travis (2009-04-21). "IGN Presents the History of Sega (page 4)". IGN. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Retro Gamer staff (2006). "Retroinspection: Mega Drive". Retro Gamer (27). Imagine Publishing: 42-47.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b McFerran, Damien (2012-02-22). "The Rise and Fall of Sega Enterprises". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 447. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Sheff, David (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children. New York: Random House. p. 352. ISBN 0-679-40469-4.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 404–405. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b Fahs, Travis (2009-04-21). "IGN Presents the History of Sega (page 5)". IGN. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "Tectoy History". Tectoy. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ^ Tiago Tex Pine (2008-02-26). "How Piracy can Break an Industry - the Brazilian Case". Game Producer Blog. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Zachariah, Reeba. "Game for success." The Times of India. 19 August 2011. Retrieved on 2 November 2011. "At that point Sega was being distributed by Shaw Wallace Electronics , owned by the late liquor baron Manu Chhabria. The products were being sold at Rs 18,000."

- ^ "Screen digest." Screen Digest Ltd., 1995. Retrieved from Google Books on 2 November 2011. "Sega tackles Indian market with local maker From spring 1995, Sega will start manufacturing video games consoles in India with local partner Shaw Wallace. Move will circumvent 80 per cent import tariff on games units which currently[...]"

- ^ "Super Gam*Boy" (in Korean). Gamer'Z Magazine. December 2009: 181.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Super Aladdin Boy" (in Korean). Game Champ Magazine. December 1992: 25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 405. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 406–408. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b c Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 424–431. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 428. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 433, 449. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 434, 448–449. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Pete Hisey (1992-06-01). "16-bit games take a bite out of sales — computer games". Discount Store News.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Damien McFerran. "Retroinspection: Mega-CD". Retro Gamer. 61. London, UK: Imagine Publishing: 84.

During the run-up to the Western launch of Mega-CD ... [Former Sega of America technical director Scot Bayless] mentioned the fact that you could just 'blast data into the DACs'. [The PR guys] loved the word 'blast' and the next thing I knew 'Blast Processing' was born."

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "The Essential 50 Part 28 - Sonic the Hedgehog from 1UP.com". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 449. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ CVG Staff (2013-04-14). "History Lesson: Sega Mega Drive". CVG. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

Granted, the Mega Drive wasn't met with quite the same levels of enthusiasm in Japan, but in the US and Europe the Mega Drive often outsold the SNES at a ratio of 2:1.

- ^ Gross, Neil (1994-02-21). "Nintendo's Yamauchi: No More Playing Around". Business Week.

His first priority is fixing the disaster in the U.S. market, where Nintendo's share of the 16-bit machine business plummeted from 60% at the end of 1992 to 37% a year later

- ^ Greenstein, Jane (1995-01-13). "Game makers dispute who is market leader". Video Business.

Sega said its products accounted for 55% of all 16-bit hardware sales for 1994

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Greenstein, Jane (1997). "Don't expect flood of 16-bit games". Video Business.

1.4 million units sold during 1996

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Matthew T. Clements & Hiroshi Ohashi (October 2004). "Indirect Network Effects and the Product Cycle: Video Games in the U.S., 1994-2002" (PDF). NET Institute. pp. 12, 24. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Sega Visions Interview with Yuji Naka". 1992. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sheffield, Brandon (4 December 2009). "Out of the Blue: Naoto Ohshima Speaks". Gamasutra. UBM plc. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

The original Nights was chiefly made with the Japanese and European audiences in mind -- Sonic, meanwhile, was squarely aimed at the U.S. market.…[Sonic is] a character that I think is suited to America -- or, at least, the image I had of America at the time. … Well, he's blue because that's Sega's more-or-less official company color. His shoes were inspired by the cover to Michael Jackson's Bad, which contrasted heavily between white and red -- that Santa Claus-type color. I also thought that red went well for a character who can run really fast, when his legs are spinning.

- ^ Yahoo Playback. "Yahoo Playback #94". Yahoo, Inc. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Brian Ashcraft. "Sonic's Shoes Inspired by Michael Jackson". Kotaku. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ "Masato Nakamura interview" (flash). Sonic Central. Retrieved 2006-02-07.

- ^ a b McFerran, Damien "Damo" (2007-03-08). "Hardware Focus - Sega Megadrive / Genesis". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "This Month in Gaming History". Game Informer. 12 (105): 117. 2002.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 381. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ a b c d e f Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc., 977 F.2d 1510 (9th Cir. 1992)

- ^ a b c Graham, Lawrence D. (1999). Legal Battles That Shaped the Computer Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 112–118. ISBN 1-56720-178-4.

- ^ a b c d Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 383. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 382. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ a b Cohen, Julie E. (1995). "Reverse Engineering and the Rise of Electronic Vigilantism: Intellectual Property Implications of "Lock-Out" Programs". Southern California Law Review. 68: 1091–1202.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 384. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 386. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ "Court: Copying Sega's Code Ok an Appeals Court Ruling Protects The Practice of 'Reverse Engineering.'". San Jose Mercury News – via NewsBank (subscription required) . Associated Press. 1992-09-01.

- ^ Stuckey, Kent D. (1996). Internet and Online Law. Law Journal Press. p. 6.37. ISBN 1-58852-074-9.

- ^ "Accolade Gets Boost In Case Against Sega". San Jose Mercury News – via NewsBank (subscription required) . 1993-01-08.

- ^ "Accolade Can Continue Making Genesis Games". San Jose Mercury News – via NewsBank (subscription required) . 1993-01-26. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The Legal Game". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 388. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Cifaldi, Frank (2010-04-30). "This Day in History: Sega and Accolade Settle Their Differences". 1UP.com.

- ^ Langberg, Mike (1993-05-01). "Accolade, Sega Settle 'Reverse Engineering' Case Out of Court". San Jose Mercury News – via NewsBank (subscription required) . Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kent, Steven L. (2001). "Moral Kombat". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b c d Ray Barnholt (2006-08-04). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the Super NES". 1UP.com. p. 4. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ Burgess, John (1994-01-11). "Sega to Withdraw, Revise "Night Trap"". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 508, 531. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 535. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ "Majesco Sales, Inc. - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ a b c Sega Service Manual (Supplement): Genesis II/Mega Drive II. Sega Enterprises, Ltd. 1993.

- ^ Sega Genesis Instruction Manual. Sega Enterprises, Ltd. 1989.

- ^ Sega Genesis Instruction Manual (Model 2). Sega Enterprises, Ltd. 1993.

- ^ a b c d e f Horowitz, Ken (2004-08-03). "Genesis Accessory & Peripheral Guide". Sega-16. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Beuscher, David. "Sega Genesis - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Kimak, Jonathan (2008-06-05). "The 6 Most Ill-Conceived Video Game Accessories Ever". Cracked.com. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Harris, Craig (2006-02-21). "Top 10 Tuesday: Worst Game Controllers". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-01-14. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ "Quadro-Power" (in German). Joker Verlag. 1994-03-30. p. 29.

- ^ a b Redsell, Adam (2012-05-20). "SEGA: A Soothsayer of the Game Industry". IGN. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (2004-11-12). "Xband: Online Gaming's First Big Try". Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Ken (2006-03-17). "Sega's SVP Chip: The Road not Taken?". Sega-16. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c d e Beuscher, David. "Sega CD - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e Beuscher, David. "Sega Genesis 32X - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ^ a b c d Parish, Jeremy (2012-10-16). "20 Years Ago, Sega Gave Us the Sega CD". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ^ a b c d e Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The War". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ "Sega v Nintendo: Sonic Boom". The Economist – via ProQuest (subscription required) . 1992-01-25. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c Birch, Aaron (2005). "Next Level Gaming: Sega Mega-CD" (17). Retro Gamer Magazine: 36–42.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Marriott, Scott Alan. "Sega Genesis 32X CD - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ^ Snow, Blake (2007-07-30). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2007-05-08. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Levi (2008-10-24). "32X Follies". IGN. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ a b c d Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The "Next" Generation (Part 1)". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Sega Service Manual: Genesis II/Mega Drive II. Sega Enterprises, Ltd. 1993.

- ^ Marriott, Scott Alan. "Sega Genesis CDX - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Marriott, Scott Alan. "Sega Genesis Nomad - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Marriott, Scott Alan. "JVC X'Eye - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ^ Marriott, Scott Alan. "Pioneer LaserActive - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ^ Sheffield, Brandon. "A Casual Rebirth: The Remaking of Majesco". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ^ a b "Innex Launches Products Containing Licensed Sega Genesis Titles In Time For Q4 Holiday Season". Innex Inc. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "Top 25 Videogame Consoles of All Time". IGN. 2009-09-04. Archived from the original on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ Top Ten Consoles (Flash video). GameTrailers. 2007-04-19. Event occurs at 4:44. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Reisinger, Don (2008-01-25). "The SNES is the greatest console of all time". CNET Blog Network. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Sztein, Andrew (2008-03-28). "The Top Ten Consoles of All Time". GamingExcellence. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Buffa, Chris (2008-03-05). "Top 10 Greatest Consoles". GameDaily. Archived from the original on 2008-03-09. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ "Genesis Emulators". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ^ Retro Gamer staff (2005). "Retro Coverdisc". Retro Gamer (15). Live Publishing: 105.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ "GameTap Sega Catalogue". GameTap. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ "Console Classix Sega Genesis games". Console Classix. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (2004-11-03). "IGN: Sonic Mega Collection Plus Review". IGN. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ Miller, Greg. "IGN's review of Sonic's Ultimate Genesis Collection". Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ a b Tor Thorsen (2007-10-18). "GDC 06: Revolution to play Genesis, TurboGrafx-16 games". GameSpot. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (2009-06-10). "Sega Vintage Collection 2 games Hit Xbox Live Arcade". Kotaku. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "Beggar Prince". Super Fighter Team. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b McFerran, Damien (2011-07-01). "Interview: Star Odyssey and The Challenge of Bringing Dead Games Back to Life". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Horowitz, Ken (2008-09-05). "Preview: Pier Solar at Sega-16.com". Sega-16. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (2008-10-03). "Independent's Day, Vol. 5: Pier Solar Flares (page 1)". IGN. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (2008-10-03). "Independent's Day, Vol. 5: Pier Solar Flares (page 2)". IGN. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ Melanson, Donald (2007-11-13). "Brazil's TecToy cranks out Mega Drive portable handheld". Engadget. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ "Mega Drive Guitar Idol - 87 jogos". TecToy. Archived from the original on 2009-08-26. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ a b "Cartridge Console With 15 Sega Megadrive Games". Blaze Europe. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ Reed, Kristen (2008-08-24). "SEGA Mega Drive Handheld". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

External links

- Mega Drive at Sega Archives (official website by Sega of Japan) (in Japanese)