French people

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|January 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

- For a specific analysis of the population of France, see Demographics of France. For an analysis on the nationality and identity of France, see French citizenship and identity"

| French nationality/French speaking/French ancestry claimed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:Frchmn.JPG| | |||||||

| French nationals | French speakers | French ancestry claimed | |||||

| France | 55,242,880 [1] | ||||||

| United States of America | 85,010 [2] | 387,915 [3] | 8,309,666 [4] | ||||

| Canada | 44,181 [5] | 6,703,325 [6] | 4,710,580 [7] | ||||

| Switzerland | 116,454 [8] | 1,485,100 [9] | |||||

| Belgium | 114,943 [10] | [11] | |||||

Definition of "French People"

The French people (French: les Français, which etymologically derives from the word Franks, even though very little direct ascendency can be deduced from the Franks to the modern 21st century French people) are the sovereign of France, composed of all French citizens, regardless of ethnic origins or religious opinions. The French people therefore comprise all French citizens, including the French overseas departments and territories. Henceforth, members from any ethnic group can be included in the French people, as long as they have French nationality, whether by jus soli ("right of territory") or by naturalization.

The US Department of State defines the "French people" as consisting of a "Celtic and Latin with Teutonic" majority, with "Slavic, North African, Sub-Saharan African, Indochinese, and Basque minorities".[12] This definition is contested by many for a variety of reasons:

- Lumping all the indigenous French together into an inexistant "Celtic and Latin with Teutonic ethnic group" does not take into account ethnic cleavages within the French state (occitans, Bretons etc...). Many of these peoples did not speak the French language until the beginning of the 20th century.

- Consequently, it may not be unacceptable to define an ethnic group solely by the fact that its members are white, western European and indigenous to the geographical region that is now France. Especially when, in many cases, there is little or no significant cultural difference between them and French citizens whose parents or grandparents were immigrants.

- The list of minorities stemming from immigration is simplistic and incomplete. Large minorities in France include the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Armenian and Greek, which are not mentioned in this definition. It is also simplistic to consider "North Africans" an ethnic minority. These can be divided into Morrocans, Tunisians and Algerians but also, and perhaps more importantly, into Imazighen (berbers) and Arabs (or arab speakers) as well as into Muslim and Jewish North Africans.

- This definition, which implies (without overtly stating) the existence of an indigenous French people as opposed to immigrant minorities, is offensive to many French citizens as it is contrary to the principles of the French Republic and Constitution as well as to the basis of modern day French identity. See: French citizenship and identity At the same time, it must be admitted that the definition used is careful in not calling the indigenous majority "ethnic French". The possible inclusion of the Basque (a separate people originating in the Southwestern border with Spain) among the list of otherwise immigrant minorities also helps in purposely blurring the distinction between French of foreign and indigenous origin.

Red/pink: Occitan or langue d'oc.

Green/yellow: Langue d'oïl.

Blue: Franco-provençal.

In the past years, the debate on social discrimination has been more and more important, sometimes mixing itself with ethnic issues, in particular concerning the "second-generation immigrants". Indeed, France has exhibited a high rate of immigration from Europe, Africa and Asia throughout the 20th century, explaining that a large minority of the French population has various ethnic ascendencies. According to Michèle Tribalat, researcher at INED, it is very difficult to estimate the number of French immigrants or born to immigrants, because of the absence of official statistics. Only three attempts have been made: in 1927, 1942 and 1986. According to this 2004 study, among about 14 millions people of foreign ascendency (immigrants or with at least one parent or grandparent who is an immigrant), 5.2 millions are from South-European ascendency (Italy, Spain, Portugal), and 3 millions come from the Maghreb [13]. Henceforth, 25% of the French people have at least one immigrant parent or grandparent. No recognized studies have been done covering wider timescales.

Abroad, the French language is spoken in different countries, in particular the former French colonies. However, speaking the French language is completely distinct from being French: one can speak French without being French, and one can be French without speaking the language. French-speaking people living in Switzerland (Romandy), are not from France, do not share their history with France, are often not catholic (in fact they welcomed religiously persecuted Huguenot), are very proud of their own identity, and obviously do not consider themselves "French". Native Anglophone Blacks in the island of Saint-Martin hold the French nationality even though they do not speak the language, while their neighbouring Francophone Haitian illegals may be able to speak some French yet remain foreigners. Furthermore, although nowadays most French people speak the French language as their native tongue, there have been periods of history when large groups of French citizens had other first languages (local dialects, German in Alsace, etc). Large numbers of people of French ancestry outside Europe speak other first languages, particularly English throughout most of North America, Spanish in southern South America and Afrikaans in South Africa.

The United States Census Bureau and Statistics Canada collect claims of French ancestry and ethnic origin among US and Canadian citizens, asking those individuals completing long form census questionnaires to define themselves. The questions asked in the US and Canada were not identical, and the data collected may not be commensurable. However, this may not be sufficient in defining these people as an ethnic group, as they are not necessarily "readily distinguishable" from other US or Canadian citizens. Note that the data is extrapolated, from a very large sample, to produce national figures.

History

- Main article: History of France

The term "French" (coming from the Franks) must not be mistaken with the modern concept of French citizenship, which is a heritage of the 1789 French Revolution: to be French, according to the first article of the Constitution, is to be a citizen of France, regardless of one's origin, race, or religion (sans distinction d'origine, de race ou de religion). Furthermore, because of France's history of promoted "miscegenation" (le métissage), a term which has recently gained a broader use in the society and an even more flattering sense in the French language, the origins of modern French nationals can be traced to just about any ethnic group and anyway less and less from Europe. According to her principles, France has devoted herself the destiny of a proposition nation, a generic territory where people are bounded only by the French language and the assumed willingness to live together. Today, peace and harmony are expected to flourish into what could be seen as an identity denial yet is said to be a source of pride for many French, though it may seem weird in countries that rely on multiculturalism like the USA or national homogeneity like Japan. Most French citizens already embrace the idea which postulates that they themselves take part of a mixed-race republic (la République métissée). Unfortunately, persistent racism and discrimination towards French citizens with origins in Maghreb and West Africa and possibly the dissatisfaction among growing cultural enclaves (communautarisme) still stain the generous ideal. The 2005 French riots that happened in difficult suburbs (les quartiers sensibles) were an example of such tensions that may be interpreted as ethnical demands, though mistakenly most of the time.

History of Gaul

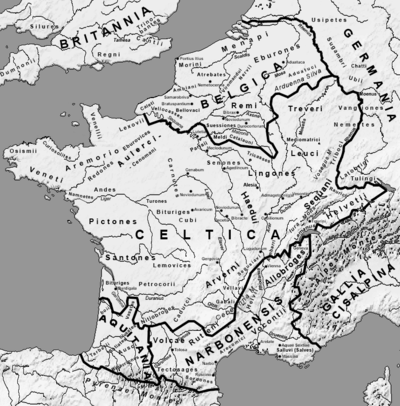

Gallia Narbonensis is inhabited or influenced by Romans and Greeks.

Aquitania is inhabited or influenced by Basques.

Belgica is influenced by Germanic tribes.

In the pre-Roman era, all of Gaul (an area of Western Europe that encompassed all of what is known today as France, Belgium, part of Germany and Swiss, and Northern Italy) was inhabited by a variety of peoples who were known collectively as the Gaulish tribes. Their ancesters were Celtic immigrants who came from Central Europe in VIIth century BC, and dominated natives people (for the majority Ligures).

Gaul was conquered in 58-51 BC by the Roman legions under the command of General Julius Caesar (except south-east which was already conquered about one century ago). The area then became part of the Roman Empire. Over the next five centuries the two cultures and peoples intermingled, creating a hybridized Gallo-Roman culture. The old Celtic tongues had been largely reduced to a mere influence over the various Vulgar Latin dialects that had come to dominate communications in the region, dialects that would later develop into the French language. Today, the last redoubt of Celtic culture and language in France can be found in the northwestern region of Brittany, although this is not the result of a survival of Gaulish language but of medieval migration from Cornwall.

The Franks

With the decline of the Roman Empire in Western Europe a third people entered the picture: the Franks. The Franks were a Germanic tribe that began filtering across the Rhine River from present-day Germany in the third century. By the early sixth century the Franks, led by the Merovingian king Clovis I and his sons, had consolidated their hold on much of modern-day France, the country to which they gave their name. The other major Germanic people to arrive in France were the Normans, Viking raiders from modern Denmark and Norway, who occupied the northern region known today as Normandy in the 9th century. The Vikings eventually intermarried with the local people, converting to Christianity in the process. It was the Normans who, two centuries later, would go on to conquer England. Eventually, though, the independent Norman duchy was incorporated back into the French kingdom in the Middle Ages.

15th to 18th century

In the roughly 900 years after the Norman invasions France had a fairly settled population [citation needed]. Unlike elsewhere in Europe, France experienced relatively low levels of emigration to the Americas, with the exception of the Huguenots. However, significant emigration of mainly Roman Catholic French populations led to the settlement of the provinces of Quebec and Louisiana, both (at the time) French possessions, as well as colonies in the West Indies, Mascarene islands and Africa.

19th to 21st century

France's population dynamics began to change in the middle of the 19th century, as France joined the Industrial Revolution. The pace of industrial growth pulled in millions of European immigrants over the next century, with especially large numbers arriving from Poland, Belgium, Portugal, Italy, and Spain.

In the 1960s, a second wave of immigration came to France, which need it for reconstruction purposes and cheaper labour after the devastation brought upon by World War II. French entrepreneurs went to Maghreb countries looking for cheap labour, thus encouraging a work-immigration to France. Their settlement was officialized with Jacques Chirac's family regrouping act of 1976 (Le regroupement familial), a law now attacked by Nicolas Sarkozy and Chirac himself. Since then, immigration has became more various, although France stopped being a major immigration country compared to other European countries.

Population with French ancestry

There is a sizeable population claiming ethnic French ancestry in the Western Hemisphere. The Canadian province of Quebec is the center of French life on the Western side of the Atlantic. It is home to the oldest French descent community and to vibrant French-language arts, media, and learning. There are sizeable French-Canadian communities scattered throughout the other provinces of Canada, particularly in Ontario and New Brunswick.

The United States is home to millions of people of French descent, particularly in Louisiana and New England. The French community in Louisiana consists of the Creoles, the descendants of the French settlers who arrived when Louisiana was a French colony, and the Cajuns, the descendants of Acadian refugees from the Great Upheaval. In New England, the vast majority of French immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries came not from France, but from over the border in Quebec. These French Canadians arrived to work in the timber mills and textile plants that were spring up throughout the region as it industrialized. Today, nearly 25% of the population of New Hampshire is of French ancestry, the highest of any state.

It is worth noting that the English and Dutch colonies of pre-Revolutionary America attracted large numbers of French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution in France. In the Dutch colony that later became New York and northeastern New Jersey, these French Huguenots, nearly identical in religion to the Dutch Reformed Church, assimilated almost completely into the Dutch community. However large it may have been at one time, it has lost all identity of its French origin, often with the translation of names (examples: de la Montagne > Vandenberg by translation; de Vaux > DeVos or Devoe by phonetic respelling). Huguenots appeared in all of the English colonies and likewise assimilated. Even though this mass settlement approached the size of the settlement of the French settlement of Quebec, it has become heavily diluted and has left little trace of any cultural influence. New Rochelle, New York is named after La Rochelle, France, one of the sources of Huguenot emigration to the Dutch colony; and New Paltz, New York, is one of the few non-urban settlements of Huguenots that did not undergo massive recycling of buildings in the usual redevelopment of such older, larger cities as New York City or New Rochelle.

Elsewhere in the Americas, the majority of the French descent population in South America can found in Argentina, Brazil and Chile (families Pinochet, Goulart, Hiriart, Chamot, Béthencourt, Béthancourt, Bétencourt, Bétancourt, Lanusse and more).

Apart from Quebecois, Acadians, Cajuns, other populations of French ancestry outside metropolitan France include the Caldoches of New Caledonia and the so-called Zoreilles and Petits-blancs of various Indian Ocean islands.

Ethnic claims and discontents

The far-right Front National 's discourse of La France aux Français ("France to the French") or Les Français d'abord ("French first") has distorted political life since the 1980s. Their claims of an "ethnic French" group have been adamantly refused by many other groups, which widely considered this party as racist[14]. According to the French Constitution, "French" is a nationality, not a specific ethnicity. Alain de Benoist's Nouvelle Droite movement, quite famous in the 1980s but which has since lost influence, has embraced a kind of European "white supremacy" ideology. It should be noted that many French people refuse the expression Français de souche ("Ethnic French" - literally, more like "French with roots"), which has no official validity in France though its use is widespread in everyday language.

Since the beginning of the Third Republic, it is not a tradition to categorize people according to their ethnic origins. Hence, to the difference of the US census, it is not asked of French people to define their ethnic appartenance, whichever it may be. This is explained by the Republican conception of nationality, which is, for French Republicans, based on jus soli ("right of territory"), a non-essentialist conception defended by Ernest Renan, and not on the essentialist and ethnic "objective" conception of nationality, defended by Fichte for example, which based itself on jus sanguinis ("right of blood"), traditionnaly qualified in France as an "exclusive conception". However, the 1993 reform of the Code de la nationalité which defines the Nationality law is deemed controversial by some. It commits young people born in France to foreign parents to wish the French nationality between 16 and 21. This has been criticized, some arguing that the principle of equality toward the law was not followed, since French nationality was no longer given automatically at birth, as in classical jus soli law, but was to be requested when approaching adulthood.

The massive inflow of populations from other continents, who still can be physically or culturally distinguished from Europeans, sparked much controversies in France since the early 1980s. In order to stifle any racist indigenous opposition and to provide an assimilation framework, antiracist organizations funded by the State revived the theme of "miscegenation" (le métissage) and helped giving it the dimension of a national goal. Now, the interracial blending of some former French and newcomers stands as a vibrant and boasted feature of French culture, from popular music to movies and literature. Therefore, alongside mixing of populations, exists also a cultural blending (le métissage culturel) that is present in France.

For a long time, the only objection to such positive outcomes predictably came from the far-right schools of thought. Since a few years, other unexpected voices are however beginning to question what they interpret, as the philosopher Alain Finkielkraut coined the term, as an "ideology of miscegenation" (une idéologie du métissage) that may come from what one other philosopher, Pascal Bruckner, defined as the "sob of the White man" (le sanglot de l'homme blanc). These critics have been dismissed with repugnance by the mainstream and their propagators have been labelled as new reactionaries (les nouveaux réactionnaires).

Language

- Main article: French language

The French language, the mother tongue of the majority of the world's French, is a Romance language, one of the many derived from Latin. In addition to its Latinate base, the development of French was also influenced, in both grammar and vocabulary, by the Celtic tongues of pre-Roman Gaul, the Germanic tongues of the Franks and the Norsemen/Vikings who settled in Normandy. More recently, French has been heavily influenced by other global tongues, particularly English.

French is not the only language spoken by the inhabitants of France. Other regional languages include:

- Occitan (Romance language) derivative :

- Alsatian, a Low Alemannic German dialect spoken in the French province of Alsace

- Basque, a Language isolate spoken in the southwest of France, along the border with Spain where it's also spoken.

- Breton, a Celtic language of the French province of Brittany

- Catalan, a Romance language spoken mostly in Roussillon, along the border with Spain.

- Corsican, the Romance language and Italian dialect of Corsica, a French island

- Flemish, a dialect of Dutch (Germanic)

- Savoyard, franco-provençal dialect

- Gallo, a Romance language of the French province of Brittany

- Picard or Chtimi, romance dialect of the Northern France

- Norman, romance dialect of Western France

- Poitevin, romance dialect of the Western France

- Polynesian languages, (French Polynesia)

- Créole language, (French Antilles)

See also

- List of French people

- Demographics of France

- Languages of France

- Superdupont, a parody of Superman and French chauvinism

Notes

- ^ 1999 INSEE quoted by http://www.rfi.fr/fichiers/MFI/PolitiqueDiplomatie/352.asp

- ^ Maison des français de l'étranger, French citizens registrations in French consulates, 2000 www.mfe.org pdf file

- ^ people speaking French (excluding creole) at home, US Census bureau 1990, quoted by Jack Jedwab in L'immigration et l'épanouissement des communautés de langue officielle au Canada : politiques, démographie et identité

- ^ US Census bureau 2000, French ancestry claims exclude Basque, Cajun and French canadian ancestry claims pdf file, p.4 definitions p.222 (pdf file).

- ^ Statistics Canada, Canada 2001 Census.Ethnic Origins (see sample longform census for details)[15][16]

- ^ 2000 federal census [17]

- ^ Statbel 2004 [18]

- ^ As of 2004, the population of the Région Wallonne was 3,380,498 per Statbel, of which 83,483 in the germanophone Ost-Kantone. Language censuses have been officially banned in Belgium since the linguistic frontier was fixed on 1 September 1963. See Taalgrens (nl) or Facilités linguistiques (fr).

References

External links

- Discover France

- The Rude French Myth

- INSEE (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques) site statistics in French