Uzbekistan

Republic of Uzbekistan O‘zbekiston Respublikasi | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: National Anthem of the Republic of Uzbekistan | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tashkent |

| Official languages | Uzbek and Russian |

| Demonym(s) | Uzbeks[1] |

| Government | Republic |

| Islom Karimov | |

| Shavkat Mirziyoyev | |

| Independence from the Soviet Union | |

• Formation | 17471 |

• Declared | September 1 1991 |

• Recognized | December 8 1991 |

• Completed | December 25 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 447,400 km2 (172,700 sq mi) (56th) |

• Water (%) | 4.9 |

| Population | |

• July 2005 estimate | 26,593,000 (44th) |

• Density | 59/km2 (152.8/sq mi) (136th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate |

• Total | $50.395 billion (74th) |

• Per capita | $2,283 (145th) |

| Gini (2000) | 26.8 low inequality |

| HDI (2007) | 0.702 high (113th) |

| Currency | Uzbekistan som (Uzbekiston so'mi) (UZS) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (UZT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+5 (not observed) |

| Calling code | 998 |

| ISO 3166 code | UZ |

| Internet TLD | .uz |

Uzbekistan, officially the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzbek: O‘zbekiston Respublikasi; Cyrillic: Ўзбекистон Республикаси; Russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia, formerly part of the Soviet Union. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south.

History

The territory of Uzbekistan was already populated in the second millennium BC. Early human tools and monuments have been found in the Ferghana, Tashkent, Bukhara, Khorezm (Khwarezm, Chorasmia) and Samarkand regions.

Alexander the Great conquered Sogdiana and Bactria in 327 BC, marrying Roxana, daughter of a local Bactrian chieftain. However, the conquest was supposedly of little help to Alexander as popular resistance was fierce, causing Alexander's army to be bogged down in the region.

For many centuries the region of Uzbekistan was ruled by Iranian Empires such as the Parthian and Sassanid Empires.

In the fourteenth century AD, Timur, known in the west as Tamerlane, overpowered the Mongols and built an empire. In his military campaigns, Tamerlane reached as far as the Middle East. He defeated Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, who was captured, and died in captivity. Tamerlane sought to build a capital for his empire in Samarkand. Today Tamerlane is considered to be one of the greatest heroes in Uzbekistan. He plays a significant role in its national identity and history. Following the fall of the Timurid Empire, Uzbek nomads conquered the region.

In the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire began to expand, and spread into Central Asia. The "Great Game" period is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 a second less intensive phase followed. At the start of the 19th century, there were some 2,000 miles (3,200 km) separating British India and the outlying regions of the Tsarist Russia. Much of the land in between was unmapped.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Central Asia was firmly in the hands of Russia and despite some early resistance to Bolsheviks, Uzbekistan and the rest of Central Asia became a part of the Soviet Union. On August 31 1991, Uzbekistan declared independence, marking September 1 as a national holiday.

The country now seeks to lessen gradually its dependence on agriculture - it is the world's second-largest exporter of cotton - while developing its mineral and petroleum reserves.

Politics

Constitutionally, the Government of Uzbekistan provides for democracy. In reality, the executive holds a great deal of power and the legislature and judiciary has little power to shape laws. Under terms of a December 1995 referendum, Islom Karimov's first term was extended. Another national referendum was held January 27, 2002 to yet again extend Karimov's term. The referendum passed and Karimov's term was extended by act of the parliament to December 2007. Most international observers refused to participate in the process and did not recognize the results, dismissing them as not meeting basic standards. The 2002 referendum also included a plan to create a bicameral parliament, consisting of a lower house (the Oliy Majlis) and an upper house (Senate). Members of the lower house are to be "full time" legislators. Elections for the new bicameral parliament took place on December 26, but no truly independent opposition candidates or parties were able to take part. The OSCE limited observation mission concluded that the elections fell significantly short of OSCE commitments and other international standards for democratic elections. Several political parties have been formed with government approval. Similarly, although multiple media outlets (radio, TV, newspaper) have been established, these either remain under government control or rarely broach political topics. Independent political parties were allowed to organize, recruit members, and hold conventions and press conferences, but have been denied registration under restrictive registration procedures. Terrorist bombings were carried out March 28-April 1, 2004 in Tashkent and Bukhara.

Human rights

The Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan asserts that "democracy in the Republic of Uzbekistan shall be based upon common human principles, according to which the highest value shall be the human being, his life, freedom, honor, dignity and other inalienable rights."

However, non-government human rights watchdogs, such as IHF, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, as well as United States Department of State and Council of the European Union define Uzbekistan as "an authoritarian state with limited civil rights" [2] and express profound concern about "wide-scale violation of virtually all basic human rights" [3]. According to the reports, the most widespread violations are torture, arbitrary arrests, and various restrictions of freedoms: of religion, of speech and press, of free association and assembly [4]. The reports maintain that the violations are most often committed against members of religious organizations, independent journalists, human right activists, and political activists, including members of the banned opposition parties. In 2005, Uzbekistan was included into Freedom House's "The Worst of the Worst: The World's Most Repressive Societies".

The official position is summarized in a memorandum "The measures taken by the government of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the field of providing and encouraging human rights" [5] and amounts to the following. The government does everything that is in its power to protect and to guarantee the human rights of Uzbek citizens. Uzbekistan continuously improves its laws and institutions in order to create a more humane society. Over 300 laws regulating the rights and basic freedoms of the people have been passed by the parliament. For instance, an office of Ombudsman was established in 1996 [6] . On August 2, 2005, President Islam Karimov signed a decree that will abolish capital punishment in Uzbekistan on January 1, 2008.

The 2005 civil unrest in Uzbekistan, which resulted in several hundred people being killed is viewed by many as a landmark event in the history of human rights abuse in Uzbekistan [2],[3],[4]. A concern has been expressed and a request for an independent investigation of the events has been made by the United States, European Union, the UN, the OSCE Chairman-in-Office and the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. The government of Uzbekistan is accused of unlawful termination of human life, denying its citizens freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. The government vehemently rebuffs the accusations, maintaining that it merely conducted an anti-terrorist operation, exercising only necessary force [5]. In addition, some Uzbek officials claim that "an information war on Uzbekistan has been declared" and the human rights violations in Andijan are invented by the enemies of Uzbekistan as a convenient pretext for intervention into the country's internal affairs [6].

Geography

Uzbekistan is approximately the size of Morocco and has an area of Template:Km2 to mi2. It is the 56th-largest country in the world.

Uzbekistan stretches Template:Km to mi from west to east and Template:Km to mi from north to south. Bordering Turkmenistan to the southwest, Kazakhstan and the Aral Sea to the north, and Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to the south and east, Uzbekistan is not only one of the larger Central Asian states but also the only Central Asian state to border all the other four. Uzbekistan also shares a short border with Afghanistan to the south.

Uzbekistan is a dry, landlocked country; it is one of two double-landlocked countries in the world – the other being Liechtenstein. 10% of its territory is intensely cultivated irrigated river valleys. The highest point in Uzbekistan is Adelunga Toghi at Template:M to ft.

The Climate in the Republic of Uzbekistan is continental, with little precipitation expected annually (100–200 milimeters, or 3.9–7.9 inches). The average summer temperature tends to be 40 °C, while the average winter temperature is around −23 °C.[7]

Major cities include: Bukhara, Samarqand and Tashkent.

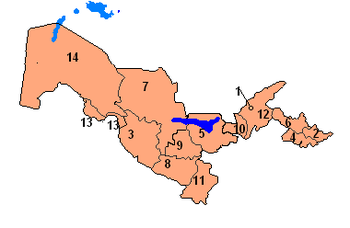

Provinces

Uzbekistan is divided into twelve provinces (viloyatlar, singular viloyat, compound noun viloyati e.g. Toshkent viloyati, Samarqand viloyati, etc.), one autonomous republic (respublika, compound noun respublikasi e.g. Qaraqalpaqstan Avtonom Respublikasi, Karakalpakistan Autonomous Republic, etc.), and one independent city (shahar. compound noun shahri , e.g. Toshkent shahri). Names are given below in the Uzbek language, although numerous variations of the transliterations of each name exist.

| Division | Capital City | Area (km²) |

Population | Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andijon Viloyati | Andijon | 4,200 | 1,899,000 | 2 |

| Buxoro Viloyati | Buxoro (Bukhara) | 39,400 | 1,384,700 | 3 |

| Farg'ona Viloyati | Farg'ona (Fergana) | 6,800 | 2,597,000 | 4 |

| Jizzax Viloyati | Jizzax | 20,500 | 910,500 | 5 |

| Xorazm Viloyati | Urganch | 6,300 | 1,200,000 | 13 |

| Namangan Viloyati | Namangan | 7,900 | 1,862,000 | 6 |

| Navoiy Viloyati | Navoiy | 110,800 | 767,500 | 7 |

| Qashqadaryo Viloyati | Qarshi | 28,400 | 2,029,000 | 8 |

| Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi | Nukus | 160,000 | 1,200,000 | 14 |

| Samarqand Viloyati | Samarqand | 16,400 | 2,322,000 | 9 |

| Sirdaryo Viloyati | Guliston | 5,100 | 648,100 | 10 |

| Surxondaryo Viloyati | Termez | 20,800 | 1,676,000 | 11 |

| Toshkent Viloyati | Toshkent (Tashkent) | 15,300 | 4,450,000 | 12 |

| Toshkent Shahri | Toshkent (Tashkent) | No Data | 2,205,000 | 1 |

The statistics for Toshkent Viloyati also include the statistics for Toshkent Shahri.

Economy

Along with many Commonwealth of Independent States economies, Uzbekistan's economy has recently shifted into high gear, recording 9.1% growth in the first quarter of 2007, along with a low inflation rate of 2.9%. [7]. However, Craig Murray, author of "Murder in Samarkand", suggests that official statistics about Uzbekistan are not trustworthy. [8]

Uzbekistan has a very low GNI per capita (US$460 giving a PPP equivalent of US$1860) [9]. Economic production is concentrated in commodities: Uzbekistan is now the world's fourth-largest producer and the world's second-largest exporter of cotton, as well as the seventh largest world producer of gold. It is also a regionally significant producer of natural gas, coal, copper, oil, silver, and uranium [10]. Agriculture contributes about 37% of GDP while employing 44% of the labor force [11]. Unemployment and underemployment are estimated to be at least 20% [12].

Facing a multitude of economic challenges upon acquiring independence, the government adopted an evolutionary reform strategy, with an emphasis on state control, reduction of imports, and self-sufficiency in energy. Since 1994, the state controlled media has repeatedly proclaimed the success of this "Uzbek Economic Model" [13] and suggested that it is a unique example of a smooth transition to the market economy while avoiding shock, pauperization, and stagnation.

The gradualist reform strategy has involved postponing significant macroeconomic and structural reforms. The state in the hands of the bureaucracy has remained a dominant influence in the economy. Corruption permeates the society: Uzbekistan's 2005 Index of perception of corruption is 137 out of 159 countries. A February 2006 report on the country by the International Crisis Group illustrates one aspect of this corruption:

- Much of Uzbekistan’s GDP growth comes from favourable prices for certain key exports, especially cotton, gold, corn, and increasingly gas, but the revenues from these commodities are distributed among a very small circle of the ruling elite, with little or no benefit for the populace at large. [14] [15]. At cotton-harvest time, all students are mobilized as unpaid labour.

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, "the government is hostile to allowing the development of an independent private sector, over which it would have no control" [16]. Thus, the national bourgeoisie in general, and the middle class in particular, are marginalized economically, and, consequently, politically.

The economic policies have repelled foreign investment, which is the lowest per capita in the CIS [17]. For years, the largest barrier to foreign companies entering the Uzbek market has been the difficulty of converting currency. In 2003, the government accepted the obligations of Article VIII under the International Monetary Fund [18], providing for full currency convertibility. However, strict currency controls and the tightening of borders have lessened the effect of this measure.

Inflation, although lower than in the mid-1990s, remained high until 2003 (an estimated 50% in 2002 and 21.9% in 2003, [19]). Tight economic policies in 2004 resulted in a drastic reduction of inflation, to 3.8% (although alternative estimates, [20] based on the price of a true market basket, put it at 15%). However, the relief appears to be transient, as the IMF estimate of CPI-based inflation in Uzbekistan in 2005 is 14.1% [21].

The government of Uzbekistan restricts non-Uzbek imports in many ways, including high import duties. Excise taxes are applied in a highly discriminatory manner to protect locally produced goods. Official tariffs are combined with unofficial, discriminatory charges resulting in total charges amounting to as much as 100 to 150% of the actual value of the product, making imported products virtually unaffordable [22]. Import substitution is an officially declared policy and the government proudly reports [23] a reduction by a factor of two in the volume of consumer goods imported. A number of CIS countries are officially exempt from Uzbekistan import duties.

Uzbekistan's external position has been strong since 2003. Thanks in part to the recovery of world market prices of gold and cotton, the country's key export commodities, expanded natural gas and some manufacturing exports, and increasing labour migrant transfers the current account turned into a large surplus - of between 9 and 11 per cent of GDP in 2003-05 - and foreign exchange reserves, including gold, more than doubled to around US$3 billion. [24]

Demographics

Uzbekistan is Central Asia's most populous country. Its 27.7 million people[1] comprise nearly half the region's total population.

The population of Uzbekistan is very young: 34.1% of its are people are younger than 14. According to official sources, Uzbeks comprise a majority (80%) of the total population. Other ethnic groups include Russians 5.5%, Tajiks 5%, Kazakhs 3%, Karakalpaks 2.5%, and Tatars 1.5%.[8] There is some controversy about the percentage of the Tajik population. While official numbers from Uzbekistan put the number at 5%, some Western scholars believe it to be much higher, going as high as 40%.[9]. There is also an ethnic Korean population that was forcibly relocated to Uzbekistan by Stalin in the 1930s. There are also small groups of Armenians in Uzbekistan, mostly in Tashkent and Samarkand. The nation is 88% Muslim (mostly Sunni, with a 5% Shi'a minority), 9% Eastern Orthodox and 3% other faiths. The US State Department's International Religious Freedom Report 2004 reports that 0.2% of the population are Buddhist (these being mostly the ethnic Koreans). The Bukharian Jews have lived in Central Asia, moslty in Uzbekistan, for thousands of years. There were also an estimated 93,000 Jews in Uzbekistan in the early 1990s (source Library of Congress Country Studies). But now, since the collapse of the USSR, most Central Asian Jews left the region for the United States or Israel. Only about 500-1,500 Jews remain in Uzbekistan.

At least 10 percent of the Uzbekistan's labour force works abroad (mostly in Russia and Kazakhstan).[10]

Uzbekistan has a 99.3% literacy rate among adults older than 15,[11] which is attributable to the free and universal education system of the Soviet Union.

Language

The Uzbek Language is the only official state language [12]. Russian is still an important language for interethnic communication, including much day-to-day technical, scientific, governmental and business use.

New language laws were enacted in 1995. The laws are very aggressive in promoting the Uzbek language, without giving similar support to Russian.

Communications

According to the official source report, as of 1 July 2007, there were 3.7 million users of cellular phones in Uzbekistan (source Uzbek agency for Communication and Information (UzACI) [25] and UzDaily.com [26]).The largest mobile operator in terms of number of subscribers is MTS-Uzbekistan [27] (former Uzdunrobita and part of Russian Mobile TeleSystems) and it is followed by Beeline [28](part of Russia's Beeline) and Coscom [29] (owned by US MCT Corp., but there is news that it is selling its asset to TeliaSonera [30]).

As of 1 July 2007, the estimated number of internet users was 1.8 million, according to UzACI.

Transportation

Tashkent, the nation's capital and largest city, has a three-line subway built in 1977, and expanded in 2001 after ten years' independence from the Soviet Union. Uzbekistan is currently the only country in Central Asia with a subway system, and it is considered to be one of the cleanest systems in the world.[citation needed] There are government operated trams, buses and trolley buses running across the city. There are also many taxis, both registered and unregistered. Uzbekistan has car-producing plants which produce modern cars. The car production is supported by the government and the Korean auto company Daewoo. The Uzbek government acquired a 50% stake in Daewoo in 2005 for an undisclosed sum, and in May 2007 UzDaewooAuto, the car maker, signed a strategic agreement with General Motors-Daewoo Auto and Technology (GMDAT) [31]. The government also bought a stake in Turkey's Koc in SamKocAuto, a producer of small buses and lorries. Afterwards, it signed an agreement with Isuzu Motors of Japan to produce Isuzu buses and lorries [32][33].

Train links connect many towns within Uzbekistan, as well as neighbouring ex-republics of the Soviet Union. Moreover, after independence two fast-running train systems were established. Also, there is a large airplane plant that was built during the Soviet era, Tashkent Chkalov Aviation Manufacturing Plant, or ТАПОиЧ in Russian. The plant originated during World War II, when production facilities were evacuated south and east to avoid capture by advancing Nazi forces. Until the late 1980s, the plant was one of the leading airplane production centers in the USSR, but with collapse of the Soviet Union its manufacturing equipment became outdated, and most of the workers were laid off. Now it produces only a few planes a year, but with interest from Russian companies growing in it, there are rumors of production-enhancement plans.

Military

Uzbekistan possesses the largest military force in the Central Asian region, having around 65,000 people in uniform. Its structure is inherited from the Soviet armed forces, although it is moving rapidly toward a fully restructured organization, which will eventually be built around light and Special Forces. The Uzbek Armed Forces' equipment is not modern, and training, while improving, is neither uniform nor adequate for its new mission of territorial security. The government has accepted the arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union, acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (as a non-nuclear state), and supported an active program by the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) in western Uzbekistan (Nukus and Vozrozhdeniye Island). The Government of Uzbekistan spends about 3.7% of GDP on the military but has received a growing infusion of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and other security assistance funds since 1998. Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S., Uzbekistan approved the U.S. Central Command's request for access to a vital military air base, Karshi-Khanabad Airbase, in southern Uzbekistan. However Uzbekistan demanded that the U.S. withdraw from the airbases after the Andijan massacre and the U.S. reaction to this massacre. The last US troops left Uzbekistan in November 2005.

Foreign relations

Uzbekistan joined the Commonwealth of Independent States in December 1991. However, it is opposed to reintegration and withdrew from the CIS collective security arrangement in 1999. Since that time, Uzbekistan has participated in the CIS peacekeeping force in Tajikistan and in UN-organized groups to help resolve the Tajik and Afghan conflicts, both of which it sees as posing threats to its own stability.

Previously close to Washington (which gave Uzbekistan half a billion dollars in aid in 2004, about a quarter of it military), the government of Uzbekistan has recently restricted American military use of the airbase at Karshi-Khanabad for air operations in neighboring Afghanistan (see AP article).Uzbekistan was an active supporter of U.S. efforts against worldwide terrorism and joined the coalitions that have dealt with both Afghanistan and Iraq. The relationship between Uzbekistan and the United States began to deteriorate after the so-called "color revolutions" in Georgia and Ukraine (and to a lesser extent Kyrgystan). When the U.S. joined in a call for an independent international investigation of the bloody events at Andijon, the relationship took an additional nosedive, and President Islam Karimov changed the political alignment of the country to bring it closer to Russia and China, countries which chose not to criticize Uzbekistan's leaders for their alleged human rights violations.

In late July 2005, the government of Uzbekistan ordered the United States to vacate an air base in Karshi-Kanabad (near the Uzbek border with Afghanistan) within 180 days. Karimov had offered use of the base to the U.S. shortly after 9/11. It is also believed by some Uzbeks that the protests in Andijan were brought about by the UK and US influences in the area of Andijan. This is another reason for the hostility between Uzbekistan and the West.

Uzbekistan is a member of the United Nations (since March 2, 1992), the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, Partnership for Peace, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It belongs to the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and the Economic Cooperation Organization (comprised of the five Central Asian countries, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). In 1999 , Uzbekistan joined the GUAM alliance (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova), which was formed in 1997 (making it GUUAM), but pulled out of the organization in 2005. Uzbekistan is also a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and hosts the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent. Uzbekistan joined the new Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO) in 2002. The CACO consists of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. It is a founding member of, and remains involved in, the Central Asian Union, formed with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and joined in March 1998 by Tajikistan.

In September 2006, UNESCO presented Islam Karimov an award for Uzbekistan's preservation of its rich culture and traditions. Despite criticism, this seems to be a sign of improving relationships between Uzbekistan and the West.

The month of October 2006 also saw a decrease in the isolation of Uzbekistan from the West. The EU announced that it was planning to send a delegation to Uzbekistan to talk about human rights and liberties, after a long period of hostile relations between the two. Although it is equivocal about whether the official or unofficial version of the Andijan Massacre is true, the EU is evidently willing to ease its economic sanctions against Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, it is generally assumed among the Uzbek population that the Uzbek government will stand firm in maintaining its close ties with the Russian Federation and in its theory that the 2004-2005 protests in Uzbekistan were promoted by the USA and UK.

Culture

Uzbekistan has a wide mix of ethnic groups and cultures, with the Uzbek being the majority group. In 1995 about 71% of Uzbekistan's population was Uzbek. The chief minority groups were Russians (8%), Tajiks (officially 5%, but believed to be much higher), Kazaks (4%), Tatars (2.5%), and Karakalpaks (2%). It is said however that the number of non-indigenous people living in Uzbekistan is decreasing as Russians and other minority groups slowly leave and Uzbeks return from other parts of the former Soviet Union.

When Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991 it was widely believed that Muslim fundamentalism would spread across the region. The expectation was that an Islamic country long denied freedom of religious practice would undergo a very rapid increase in the expression of its dominant faith. As of 1994 about half of Uzbeks were said to be muslim, though in an official survey few of that number had any real knowledge of the religion or knew how to practice it. However Islam is increasing in the region.

Uzbekistan has a high literacy rate with about 99.3% of adults above the age of 15 being able to read and write. However with only 88% of the under 15 population currently enrolled in education this figure may drop in the future [citation needed] . Uzbekistan has encountered severe budgeting shortfalls in its education program. The education law of 1992 began the process of theoretical reform, but the physical base has deteriorated, and curriculum revision has been slow.

Uzbek universities churn out almost 600,000 graduates annually.

Environment

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2007) |

Uzbekistan's environmental situation ought to be a major concern among the international community. Decades of questionable Soviet policies in pursuit of greater cotton production has resulted in a catastrophic scenario. The agricultural industry appears to be the main contributor to the pollution and devastation of the air and water in the country. [34]

The Aral Sea disaster is a classic example. The Aral Sea used to be the fourth largest inland sea on Earth, acting as an influencing factor in the air moisture. [35] Since the 1960s, the decade when the misuse of the Aral Sea water began, it has shrunk to less than 50% of its former area, and decreased in volume threefold. Reliable - or even approximate - data has not been collected, stored or provided by any organization or official agency. The numbers of animal deaths and human refugees from the area around the sea can only be guessed at. The question of who is responsible for the crisis - the Soviet scientists and politicians who directed the distribution of water during the sixties, or the post-Soviet politicians who did not allocate sufficient funding for the building of dams and irrigation systems - remains open.

Due to the almost insoluble Aral Sea problem, high salinity is widespread in Uzbekistan. The vast majority of the nation's water resources are used for farming, which consumes nearly 94% of the water usage. [36] This results in a heavy use of pesticides and fertilizers. [37]

Bibliography

- Chasing the Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia by Tom Bissell

- A Historical Atlas of Uzbekistan by Aisha Khan

- The Modern Uzbeks From the 14th century to the Present: A Cultural History by Edward A. Allworth

- Nationalism in Uzbekistan: Soviet Republic's Road to Sovereignty by James Critchlow

- Odyssey Guide: Uzbekistan by Calcum Macleod and Bradley Mayhew

- Uzbekistan: Heirs to the Silk Road by Johannes Kalter and Margareta Pavaloi

- "Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East?" by Ted Rall

- Murder in Samarkand - A British Ambassador's Controversial Defiance of Tyranny in the War on Terror by Craig Murray

References

- ^ a b CIA World Factbook, Uzbekistan Cite error: The named reference "cia1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ US Department of State, 2004 Country report on Human Rights Practices in Uzbekistan, released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, February 28, 2005

- ^ IHF, Human Rights in OSCE Region: Europe, Central Asia and North America - Uzbekistan, Report 2004 (events of 2003), 2004-06-23

- ^ OMCT and Legal Aid Society, DENIAL OF JUSTICE IN UZBEKISTAN - an assessment of the human rights situation and national system of protection of fundamental rights, April 2005.

- ^ Embassy of Uzbekistan to the US, Press-Release: THE MEASURES, TAKEN BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN IN THE FIELD OF PROVIDING AND ENCOURAGING HUMAN RIGHTS, October 24, 2005

- ^ UZBEKISTAN DAILY DIGEST, UZBEKISTAN'S OMBUDSMAN REPORTS ON 2002 RESULTS, December 25, 2007

- ^ [1]

- ^ 1996 data; CIA World factbook, Uzbekistan

- ^ D. Carlson, "Uzbekistan: Ethnic Composition and Discriminations", Harvard University, August 2003

- ^ International Crisis Group, Uzbekistan: Stagnation and Uncertainty, Asia Briefing N°67, 22 August 2007 (free registration needed to view full report)

- ^ 2003 data; CIA World Factbook, Uzbekistan

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan

- Anora Mahmudova, AlterNet, May 27, 2005, Uzbekistan’s Growing Police State (checked 2005-11-08)

- Manfred Nowak, Radio Free Europe, 2005-06-23, UN Charges Uzbekistan With Post-Andijon Torture,

- Gulnoza Saidazimova, Radio Free Europe, 2005-06-22, Uzbekistan: Tashkent reveals findings on Andijon uprising as victims mourned

- BBC News, 'Harassed' BBC shuts Uzbek office, 2005-10-26 (checked 2005-11-15)

- CIA - The World Factbook — Uzbekistan

- Denial of Justice in Uzbekistan, report to OMCT

- The worst of the worst, the world's most repressive societies, 2005.

- The measures, taken by the Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the field of providing and encouraging human rights

- Uzbekistan' s Ombudsman reports on 2002 results

- Jeffrey Thomas, US Government Info September 26, 2005 Freedom of Assembly, Association Needed in Eurasia, U.S. Says,

- Robert McMahon, Radio Free Europe, 2005-06-07 Uzbekistan: Report Cites Evidence Of Government 'Massacre' In Andijon

- Amnesty International, public statement "Uzbekistan: Independent international investigation needed into Andizhan events"

- People's Voice, 2005-05-17 Andijan events: truth and lies

- Interview with Akmal Saidov, kreml.org, 2005-10-17 Andijon events are used as a pretext for putting an unprecedented pressure on Uzbekistan

- Worldbank per-country data on GNI and PPP per capita

- UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Country Report on Uzbekistan

- Islam Karimov's interview to Rossijskaya Gazeta, 1995-07-07 Principles of Our Reform

- 2005 Index of Economic Freedom, Uzbekistan

- US Department of State, Uzbekistan: 2005 Investment Climate Statement

- The Republic of Uzbekistan Accepts Article VIII Obligations

- US Department of State, 2005-07 Background Note: Uzbekistan

- Asian Development Outlook for 2005, report on Uzbekistan

- IMF , 2005-09-24 Republic of Uzbekistan and the IMF

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan report on International Trade

- Uzbekistan: In for the Long Haul: report on the international response to Uzbekistan by the International Crisis Group

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.