Shakespeare authorship question

The Shakespearean authorship question is the debate, dating back to the 18th century, over whether the works attributed to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon were actually written by another writer, or group of writers.[3] Numerous alternative candidates have been proposed including Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, William Stanley (Earl of Derby), and Edward de Vere (Earl of Oxford).[4].

Admirers of Shakespeare's works are often disappointed by the lack of available information about the author. In Who Wrote Shakespeare (1996), John Michell notes, "The known facts about Shakespeare's life ... can be written down on one side of a sheet of notepaper." He cites Mark Twain's satirical expression of the same point in Is Shakespeare Dead? (1909). There are large gaps in the historical record of his life and there are no surviving letters written by him. His detailed will mentions no books, plays, poems or writings of any kind and he expressed no direct opinions about his art. Almost nothing is known about his personality, and although much can be inferred about him from his writings, the lack of concrete information leaves him an enigmatic figure. Mainstream scholars, however, find this lack of information unsurprising given the passage of time, and given that the lives of commoners were not as documented as those of the nobility and the upper-classes. They also note that information about Elizabethan theatre practitioners is fragmentary, and that a similar scarcity of information is the case with other period playwrights.

The second major reason for doubt is the enormous vocabulary used in Shakespeare's works (approximately 29,000 different words). This is almost six times as large as the vocabulary used in the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, which employs only about 5,000 different words. Many critics have found it difficult to believe that a 16th-century commoner, whose formal education is still a mystery, could be so well-versed in the English language, let alone in politics, the law, and foreign languages. There are no existing admission or attendance records for Shakespeare at any grammar school, university, or college, and the school or schools where he might have studied are still a matter of speculation.

"Anti-Stratfordians" (defined below) assert that the available information about Shakespeare's life offers no proof that he was able to write the works attributed to him. They further suggest that other, better-recorded figures of the period are more likely candidates for the authorship, and claim that Shakespeare was simply a frontman for the true author who wished to remain anonymous. For nearly 200 years, Francis Bacon was the leading alternate authorship candidate.[5] Christopher Marlowe, William Stanley (6th Earl of Derby), and numerous other candidates have been proposed but failed to attract large followings.[6] The most popular theory of the 20th century is that Shakespeare's works were written by Edward de Vere (17th Earl of Oxford).[7] Since the 1980s, interest in the authorship debate has grown, particularly among independent scholars, theatre professionals and some academicians. This trend has continued into the 21st century.

Overview

Mainstream view

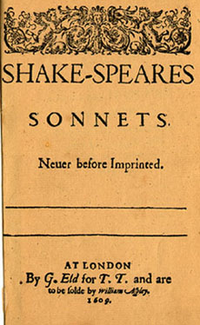

The mainstream view is that Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564. He then moved to London and became a poet, a playwright, an actor, and "sharer" (part-owner) of the favoured acting company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men (later the King's Men), which owned the Globe Theatre and the Blackfriars Theatre in London. He divided his time between London and Stratford, and retired there around 1613 before his death in 1616. Shakespeare's name appears on the title pages of fourteen of the fifteen works published during his lifetime. In 1623, after the death of most of the proposed candidates, his plays were collected for publication in the First Folio edition.

This actor is further identified by the following evidence: Shakespeare of Stratford left gifts to actors from the London company in his will, the man from Stratford and the author of the works share a common name; and commendatory poems in the 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare's works refer to the "Swan of Avon" and his "Stratford monument".[9] Mainstream scholars assume that the latter phrase refers to the funerary monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford, which refers to Shakespeare as a writer (comparing him to Virgil and calling his writing a "living art"), and was described as such by visitors to Stratford as far back as the 1630s.[citation needed] From the above evidence, the mainstream view is that William Shakespeare of Stratford, who left his home town and became an actor and playwright in London, wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Several pieces of circumstantial evidence support the Stratfordian view: Firstly, in a 1592 pamphlet by the playwright Robert Greene called "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit", Greene chastises a playwright whom he calls "Shake-scene", calling him "an upstart crow" and a "Johannes factotum" (a "Jack-of-all-trades," a man able to feign skill), thus suggesting that people were aware of a writer named Shakespeare.[10] Also, poet John Davies once referred to Shakespeare as "our English Terence", though this is a mixed reference as Cicero, Quintilian, Michel de Montaigne, and many of his contemporary Elizabethan scholars knew Terence as a front man for one or more Roman aristocratic playwrights.[10] Additionally, Shakespeare's grave monument in Stratford, built within a decade of his death, features him at a desk with a pen in hand, obviously writing something, suggesting that he was known as writer (although researchers debate whether the monument itself was altered at a later date).[10]

Authorship doubters

For authorship doubters, evidence that Shakespeare of Stratford was merely a front man for another undisclosed playwright arises from several circumstantial sources: perceived ambiguities and missing information in the historical evidence supporting Shakespeare's authorship; the assertion that the plays require a level of education (including knowledge of foreign languages) greater than that which Shakespeare is known to have possessed; circumstantial evidence suggesting the author was deceased while Shakespeare of Stratford was still living; doubts of his authorship expressed by his contemporaries; plays that he appeared to be unavailable or unable to write; coded messages asserted to be hidden in the works that identify another author; and perceived parallels between the characters in Shakespeare's works and the life of the favoured candidate.

On September 8, 2007, acclaimed British actors Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance unveiled a "declaration of reasonable doubt" on the authorship of Shakespeare's work, after the final matinee of I Am Shakespeare, a play investigating the bard's identity, performed in Chichester, England. Over the centuries, the "real" author has been suggested to be, among others, Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon, or Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford - either singly or as a group effort with other writers. The "declaration" named 20 prominent doubters of the past, including Mark Twain, Orson Welles, Sir John Gielgud and Charlie Chaplin. The document was sponsored by the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition and signed online by 300 people to encourage new research into the question. Jacobi, who voiced support for a group theory led by De Vere, and Rylance, who was featured in the authorship play, presented a copy of the document to William Leahy, head of English at Brunel University, London.[11]

Terminology

Stratfordians and anti-Stratfordians

Those who question whether William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was the primary author of Shakespeare's plays are usually referred to as anti-Stratfordians, while those who have no such doubts, are often called Stratfordians. Those who identify Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, or the Earl of Oxford as the main author of Shakespeare's plays are commonly referred to as Baconians, Marlovians, or Oxfordians, respectively.

"Shakspere" vs. "Shakespeare"

There was no standardised spelling in Elizabethan England, and throughout his lifetime Shakespeare of Stratford's name was spelled in many different ways, including "Shakespeare". Anti-Stratfordians conventionally refer to the man from Stratford as "Shakspere" (the name recorded at his baptism) or "Shaksper" to distinguish him from the author "Shakespeare" or "Shake-speare" (the spellings that appear on the publications), who they claim has a different identity. They point out that most references to the man from Stratford in legal documents usually spell the first syllable of his name with only four letters, "Shak-" or sometimes "Shag-" or "Shax-", whereas the dramatist's name is consistently rendered with a long "a" as in "Shake".[12] Stratfordians reject this convention, believing it implies that the Stratford man spelled his name differently from the name appearing on the publications.[citation needed] Because the "Shakspere" convention is controversial, this article uses the name "Shakespeare" throughout.

The idea of secret authorship in Renaissance England

In support of the possibility of Shakespeare as "frontman", anti-Stratfordians point to contemporary examples of Elizabethans discussing anonymous or pseudonymous publication by persons of high social status. Roger Ascham in his book The Schoolmaster refers to his belief that two plays attributed to the Roman dramatist Terence were secretly written by "worthy Scipio, and wise Lælius", because the language is too elevated to have been written by "a seruile stranger" such as Terence.[13] Describing contemporary writers, the dramatist and pamphleteer Robert Greene wrote that "others ... which for their calling and gravity being loth to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hands, get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses."[14] (Batillus was a minor poet in the reign of Augustus Caesar).

Common arguments used by anti-Stratfordians

Shakespeare's literacy

Some anti-Stratfordians[16] remark on the fact that Shakespeare's wife Anne and daughter Judith seem to have been illiterate (as was normal for middle-class women in the 17th century),[17] since they made marks on official documents instead of signing their names, suggesting that Shakespeare may not have taught them to write. However, his other daughter, Susannah, was able to at least sign her name.[18]Anti-Stratfordians also note that there are no surviving letters from or to Shakespeare. They maintain it would only be logical for a man of Shakespeare's writing ability to compose numerous letters, and given the man's supposed fame they find it remarkable that not one letter, or record of a letter, exists.[19]

Shakespeare's education

Anti-Stratfordians often note that there is no evidence that Shakespeare possessed the education required to have written the plays. The Stratfordian position is that Shakespeare was entitled to attend the The King's School in Stratford until the age of fourteen, where he would have studied the Latin poets and playwrights such as Plautus and Ovid.[20] The records of pupils at the school have not survived, so it cannot be proven whether Shakespeare attended or not.[21]

There is no evidence that Shakespeare attended a university, although this was not unusual among Renaissance dramatists.[citation needed] Traditionally, scholars assume that Shakespeare was partly self-educated.[citation needed] A commonly cited parallel is his fellow dramatist Ben Jonson, a man whose origins were humbler than Shakespeare's, and who rose to become court poet. Like Shakespeare, Jonson never completed and perhaps never attended university, and yet he became a man of great learning (later being granted an honorary degree from both Oxford and Cambridge).

The parallel with Jonson has been questioned,[citation needed] since there is clearer evidence for Jonson's self-education than for Shakespeare's. Several hundred books owned by Ben Jonson have been found signed and annotated by him[22] but no book has ever been proved to have been owned or borrowed by Shakespeare. In addition, Jonson had access to a substantial library with which to supplement his education.[23] One possible source for Shakespeare's self-education has been suggested: A. L. Rowse has pointed out that some of the sources for his plays have been sold at the shop of the printer Richard Field, a fellow Stratfordian of Shakespeare's age.[24]

Stratfordians note that Shakespeare's works have not always been considered to require an unusual amount of education: Ben Jonson's tribute to Shakespeare in the 1623 First Folio states that his plays were great even though he had "small Latin and less Greek". And it has been argued that a great deal of the classical learning he displays is derived from one text, Ovid's Metamorphoses, which was a set text in many schools at the time.[25] However, this explanation does not counter the argument that the author also required a knowledge of foreign languages, modern sciences, warfare, aristocratic sports such as tennis, hunting, and falconry, and the law.[26]

Shakespeare's will

William Shakespeare's will is long and explicit, listing the possessions of a successful bourgeois in detail. Anti-Stratfordians find it notable that the will makes no mention at all of personal papers, letters, or books (books were rare and expensive items at the time) of any kind. In addition, no early poems or manuscripts, plays or unfinished works are listed, nor is there any reference to the shares in the Globe Theatre that the Stratford man supposedly owned, shares that would have been exceedingly valuable.[27]

In particular, anti-Stratfordians note at the time of Shakespeare's death, 18 plays remained unpublished, and yet none of them are mentioned in his will (this contrasts with Sir Francis Bacon, whose two wills refer to work that he wished to be published posthumously).[28] Anti-Stratfordians find it unusual that Shakespeare did not wish his family to profit from his unpublished work or was unconcerned about leaving them to posterity. They find it improbable that Shakespeare would have submitted all the manuscripts to the King's Men, the playing company of which he was a shareholder. As was the normal practice at the time, Shakespeare's submitted plays were owned jointly by the members of the King's Men.[29] It was two of his fellow shareholders, John Heminge and Henry Condell – whose names were attached to a dedicatory epistle to the 1623 First Folio – who "collected" his work for publication.[30]

Shakespeare's class

Anti-Stratfordians believe that a provincial glovemaker's son who resided in Stratford until early adulthood would be unlikely to have written plays that deal so personally with the activities, travel and lives of the nobility. The view is summarized by Charles Chaplin: "In the work of greatest geniuses, humble beginnings will reveal themselves somewhere, but one cannot trace the slightest sign of them in Shakespeare. Whoever wrote [Shakespeare] had an aristocratic attitude."[31] Orthodox scholars respond that the glamorous world of the aristocracy was a popular setting for plays in this period. They add that numerous English Renaissance playwrights, including Christopher Marlowe, John Webster, Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker and others wrote about the nobility despite their own humble origins. [citation needed]

Anti-Stratfordians further suggest that the plays show a detailed understanding of politics, the law and foreign languages that would have been impossible to attain without an aristocratic or university upbringing. Orthodox scholars respond that Shakespeare was an upwardly mobile man: his company regularly performed at court and he thus had ample opportunity to observe courtly life[citation needed]. In addition, his theatrical career made him wealthy [citation needed] and he eventually acquired a coat of arms for his family and the title of gentleman, like many other wealthy middle class men in this period.

In The Genius of Shakespeare, Jonathan Bate points out that the class argument is reversible: the plays contain details of lower-class life in which aristocrats might have little knowledge. Many of Shakespeare's most vivid characters are lower class or associate with this milieu, such as Falstaff, Nick Bottom, Autolycus, Sir Toby Belch, etc.[32] Anti-Stratfordians assert that while the author's depiction of nobility was highly personal and multi-faceted, his treatment of the peasant class was quite different, including comedic and insulting names (Bullcalfe, Elbow, Bottom, Belch), often portrayed as the butt of jokes or as an angry mob.[33]

It has also been noted that in the 17th century, Shakespeare was not thought of as an expert on the court, but as a "child of nature" who "Warble[d] his native wood-notes wild" as John Milton put it in his poem L'Allegro. Indeed, John Dryden wrote in 1668 that the playwrights Beaumont and Fletcher "understood and imitated the conversation of Gentlemen much better" than Shakespeare, and in 1673 wrote of Elizabethan playwrights in general that "I cannot find that any of them had been conversant in courts, except Ben Jonson."

Against this argument is the fact that it took Ben Jonson (who had a similar low class to Shakespeare) 12 years from his first play to obtain noble patronage from Prince Henry for his commentary The Masque of Queens (1609). Anti-Stratfordians thus express doubt that Shakespeare could have obtained the Earl of Southampton's patronage for one of his first published works, the long poem Venus and Adonis (1593).

The 1604 problem

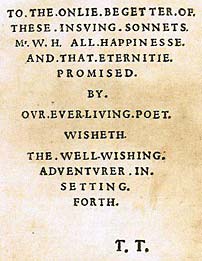

Some researchers believe certain documents imply the actual playwright was dead by 1604, the year continuous publication of new Shakespeare plays "mysteriously stopped",[34] and many mainstream scholars believe The Tempest, Henry VIII,[35] Macbeth, Timon, Pericles, King Lear and Antony and Cleopatra, so-called “later plays,” were composed no later than 1604.[36] Researchers cite Shake-Speare’s Sonnets, 1609, which appeared with “our ever-living Poet”[37] on the title page,[38] words typically used eulogizing someone who has died, yet become immortal.[39] Researchers also cite one contemporary document that strongly implies that Shakespeare, the Globe shareholder, was dead prior to 1616, when Shakespeare of Stratford died.[40] For further information on the 1604 problem, see Oxfordian theory.

Comments by contemporaries

Comments on Shakespeare by Elizabethan literary figures can be read as expressions of doubt about his authorship.

Ben Jonson had a contradictory relationship with Shakespeare. He regarded him as a friend – saying "I loved the man"[41] – and wrote tributes to him in the First Folio. However, Jonson also wrote that Shakespeare was too wordy: Commenting on the Players' commendation of Shakespeare for never blotting out a line, Jonson wrote "would he had blotted a thousand" and that "he flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped."[42] In the same work, he scoffs at a line Shakespeare said "in the person of Caesar" (presumably on stage): "Caesar never did wrong but with just cause", which Jonson calls "ridiculous,"[43] and indeed the text as preserved in the First Folio carries a different line: "Know, Caesar doth not wrong, nor without cause / Will he be satisfied" (3.1). Jonson ridiculed the line again in his play The Staple of News, without directly referring to Shakespeare. Some anti-Stratfordians interpret these comments as expressions of doubt about Shakespeare's ability to have written the plays.[44]

In Robert Greene's posthumous publication Greene's Groatsworth of Wit (1592; published, and possibly written, by fellow dramatist Henry Chettle) a dramatist labeled "Shake-scene" is vilified as "an upstart Crowe beautified with our feathers", along with a quotation from Henry VI, Part 3. The orthodox view is that Greene is criticizing the relatively unsophisticated Shakespeare for invading the domain of the university-educated playwright Greene.[citation needed] Some anti-Stratfordians claim that Greene is in fact doubting Shakespeare's authorship.[45] In Greene's earlier work Mirror of Modesty (1584), the dedication mentions "Ezops Crowe, which deckt hir selfe with others feathers" referring to Aesop's fable (the Crow, the Eagle, and the Feathers) against people who boast they have something they do not.

In John Marston's satirical poem The Scourge of Villainy (1598), Marston rails against the upper classes being "polluted" by sexual interactions with the lower classes. Seasoning his piece with sexual metaphors, he then asks:

- Shall broking pandars sucke Nobilitie?

- Soyling fayre stems with foule impuritie?

- Nay, shall a trencher slaue extenuate,

- Some Lucrece rape?". And straight magnificate

- Lewd Jovian Lust? Whilst my satyrick vaine

- Shall muzzled be, not daring out to straine

- His tearing paw? No gloomy Juvenall,

- Though to thy fortunes I disastrous fall.

There is a tradition that the satirist Juvenal became "gloomy" after being exiled by Domitian having lampooned an actor that the emperor was in love with.[46] So Marston's piece could be taken as being directed at an actor, and as questioning whether such a lower class "trencher slave" is extenuating (making light of) "some Lucrece rape". One interpretation is that it refers to The Rape of Lucrece, with Shakespeare depicted as a "broking pandar" (procurer), implicitly questioning his credentials to "sucke Nobilitie", that is, attract the Earl of Southampton's patronage of him.[citation needed]

Evidence in the poems

Both orthodox scholars and anti-Stratfordians have used Shakespeare's sonnets as evidence for their positions.

Mainstream scholars assert that the opening lines of Sonnet 135 are strong evidence against any alternative author, or at least any not named William:

- Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy Will,

- And Will to boot, and Will in overplus;

- More than enough am I that vex thee still,

- To thy sweet will making addition thus. (the italics and capitalisation are those of the original text)

The italicised puns on Shakespeare's name continue in Sonnet 136 which concludes "And then thou lovest me, for my name is Will".

In any case, imaginative works can be playful and imaginative, so the use of the name "Will" proves that the writer either:

- a) was named William and wanted to create a poetic conceit based on Will/will; or

- b) was not named William and wanted to create a poetic conceit based on the pretense that he was.

While anti-Stratfordians contend that a nobleman would not have wanted to be known as a playwright, mainstream scholars point out that this argument does not apply to poetry, which was a skill expected of an Elizabethan courtier. Poems such as Shakespeare's The Rape of Lucrece or Venus and Adonis, long narrative works on classical subjects, were a prestigious and respectable form of composition, unlike "merely popular" plays. Anti-Stratfordians respond that the contents of the Sonnets, as well as the narrative poems, touched on matters of personal and political scandal that positively required the adoption of a nom de plume by the author. They cite Sonnet 76 as clear evidence of the author's confession of the need for such a ruse although "weed" could mean the Sonnet form:

- Why write I still all one, ever the same,

- And keep invention in a noted weed,

- That every word doth almost tell my name,

- Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

Mainstream scholars find it significant that both of Shakespeare's major poetic works, the narrative poems and the sonnets, were published immediately after periods in which the theatres had been closed by an outbreak of plague. This pattern, it is suggested, is consistent with composition by a professional dramatist looking for an alternative source of income during a theatre closing.

Geographical knowledge

Most anti-Stratfordians believe that a well-traveled man wrote the plays, as many of them are set in European countries and show great attention to local details. Orthodox scholars respond that numerous plays of this period by other playwrights are set in foreign locations and Shakespeare is thus entirely conventional in this regard. In addition, in many cases Shakespeare did not invent the setting, but borrowed it from the source he was using for the plot.

Even outside of the authorship question, there has been debate about the extent of geographical knowledge displayed by Shakespeare. Some scholars argue that there is very little topographical information in the texts (nowhere in Othello or the Merchant of Venice are Venetian canals mentioned). Indeed, there are apparent mistakes: for example, Shakespeare refers to Bohemia as having a coastline in The Winter's Tale (the region is landlocked), refers to Verona and Milan as seaports in The Two Gentlemen of Verona (the cities are inland), and in All's Well That Ends Well he suggests that a journey from Paris to Northern Spain would pass through Italy.

Answers to these objections have been made by other scholars (both orthodox and anti-Stratfordian). It has been noted that The Merchant of Venice demonstrates detailed knowledge of the city, using the local word, traghetto, for the Venetian mode of transport (printed as 'traject' in the published texts[47]). One explanation given for Bohemia having a coastline is the author's awareness that the kingdom of Bohemia at one time stretched to the Adriatic.[48] Anti-Stratfordians suggest that the above information would most likely be obtained from first-hand experience of the regions under discussion; they thus conclude that the author of the plays could have been a diplomat, aristocrat or politician. In all these cases, however, a very important fact is being overlooked: the same geographical mistake was already present in Shakespeare's source, Robert Greene's Pandosto, and the play merely reproduced it.

Mainstream scholars assert that Shakespeare's plays contain several colloquial names for flora and fauna that are unique to Warwickshire, where Stratford-upon-Avon is located, for example 'love in idleness' in A Midsummer Night's Dream.[49] These names may suggest that a Warwickshire native might have written the plays. Researchers point out that the Earl of Oxford owned a manor house in Bilton, Warwickshire, although records show that he leased it out in 1574 and sold it in 1581.[50]

Candidates and their champions

History of alternative attributions

The first indirect statements regarding suspicions as to the authorship of "Shakespeare's" works comes from the Elizabethans themselves.

The first direct statements of doubt about Shakespeare's authorship were made in the 18th century, when unorthodox views of Shakespeare were expressed in three allegorical stories. In An Essay Against Too Much Reading (1728) by a 'Captain' Golding, Shakespeare is described as merely a collaborator who "in all probability cou'd not write English".[51] In The Life and Adventures of Common Sense (1769) by Herbert Lawrence, Shakespeare is portrayed as a "shifty theatrical character ... and incorrigible thief".[52] In The Story of the Learned Pig (1786) by an anonymous author described as "an officer of the Royal Navy," Shakespeare is merely a front for the real author, a chap called "Pimping Billy."

Around this time, James Wilmot, a Warwickshire clergyman and scholar, was researching a biography on Shakespeare. He traveled extensively around Stratford, visiting the libraries of country houses within a radius of fifty miles looking for records or correspondence connected with Shakespeare or books that had been owned by him. By 1781, Wilmot had become so appalled at the lack of evidence for Shakespeare that he concluded he could not be the author of the works. Wilmot was familiar with the writings of Francis Bacon and formed the opinion that he was more likely the real author of the Shakespearean canon. He confided this to one James Cowell. Cowell disclosed it in a paper read to the Ipswich Philosophical Society in 1805 (Cowell's paper was only rediscovered in 1932).

These reports were soon forgotten [citation needed]. However, Bacon would emerge again in the 19th century as the most popular alternative candidate when, at the height of bardolatry, the "authorship question" was popularised. Many 19th century doubters, however, declared themselves agnostics and refused to endorse an alternative. The American populist poet Walt Whitman gave voice to this skepticism when he told Horace Traubel, "I go with you fellows when you say no to Shaksper: that's about as far as I have got. As to Bacon, well, we'll see, we'll see."[53] Starting in 1908, Sir George Greenwood engaged in a series of well-publicized debates with Shakespearean biographer Sir Sidney Lee and author J.M. Robertson. Throughout his numerous books on the authorship question, Greenwood contented himself to argue against the traditional attribution of the works and never supported the case for a particular alternative candidate. In 1922, he joined John Thomas Looney, the first to argue for the authorship of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, in founding The Shakespeare Fellowship, an international organization dedicated to promoting discussion and debate on the authorship question. By 1975 the Encyclopedia Britannica declared that Oxford was the most probable "alternative author". Since the 1980s, support for Oxford's authorship among independent intellectuals, theatre professionals and some academicians has increased markedly.

The poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe has also been a popular candidate during the 20th century. Many other candidates -- among them de Vere's son in law William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby -- have been suggested, but have failed to gather large followings.

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

The most popular latter-day candidate is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. This theory was first proposed by J. Thomas Looney in 1920, whose work persuaded Sigmund Freud, Orson Welles, Marjorie Bowen, and many other early 20th-century intellectuals.[54] The theory was brought to greater prominence by Charlton Ogburn's The Mysterious William Shakespeare (1984), after which Oxford rapidly became the favored alternative to the orthodox view of authorship. Advocates of Oxford are usually referred to as Oxfordians.

Oxfordians base their theory on what they consider to be multiple and striking similarities between Oxford's biography and numerous events in Shakespeare's plays. Oxfordians also point to the acclaim of Oxford's contemporaries regarding his talent as a poet and a playwright; his closeness to Queen Elizabeth I and Court life; underlined passages in his Bible that they assert correspond to quotations in Shakespeare's plays;[55] parallel phraseology and similarity of thought between Shakespeare's work and Oxford's remaining letters and poetry;[56] his extensive education and intelligence, and his record of travel throughout Italy, including the sites of many of the plays themselves.[57]

Supporters of the orthodox view would dispute most if not all of these contentions. For them, the most compelling evidence against Oxford is that he died in 1604, whereas they contend that a number of plays by Shakespeare may have been written after that date. Oxfordians, and some conventional scholars, respond that orthodox scholars have long dated the plays to suit their own candidate, and assert that there is no conclusive evidence that the plays or poems were written past Oxford's death in 1604. For a dating of Shakespeare's plays according to the Oxfordian theory, see Chronology of Shakespeare's plays – Oxfordian.

Some mainstream scholars also consider Oxford's published poems to bear no stylistic resemblance to the works of Shakespeare.[citation needed] Oxfordians counter that argument by pointing out that the published Oxford poems are those of a very young man, and as such are juvenilia. They support this argument by citing parallels between Oxford's poetry and Shakespeare's early play, Romeo and Juliet.[56]

Sir Francis Bacon

In 1856, William Henry Smith put forth the claim that the author of Shakespeare's plays was Sir Francis Bacon, a major scientist, philosopher, courtier, diplomat, essayist, historian and successful politician, who served as Solicitor General (1607), Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618).

Smith was supported by Delia Bacon in her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded(1857), in which she maintains that Shakespeare was in fact a group of writers, including Francis Bacon, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser, for the purpose of inculcating a philosophic system, for which they felt that they themselves could not afford to assume the responsibility. She professed to discover this system beneath the superficial text of the plays. Constance Mary Fearon Pott (1833–1915) adopted a modified form of this view, founding the Francis Bacon Society in 1885, and publishing her Bacon-centered theory in Francis Bacon and his secret society (1891).[58]

Since Bacon commented that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue,"[59] another view is that Bacon acted alone and left his moral philosophy to posterity in the Shakespeare plays (e.g. the nature of good government exemplified by Prince Hal in Henry IV, Part 2). Having outlined both a scientific and moral philosophy in his Advancement of Learning (1605) only Bacon's scientific philosophy was known to have been published during his lifetime (Novum Organum 1620). Francis Carr has suggested that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays and Don Quixote.[60]

Supporters of Bacon draw attention to similarities between specific phrases from the plays and those written down by Bacon in his wastebook, the Promus,[61] which was unknown to the public for a period of more than 200 years after it was written. A great number of these entries are reproduced in the Shakespeare plays often preceding publication and the performance dates of those plays. Bacon confesses in a letter to being a "concealed poet"[62] and was on the governing council of the Virginia Company when William Strachey's letter from the Virginia colony arrived in England which, according to many scholars, was used to write The Tempest (see below).

Mainstream scholars are unconvinced by the Bacon theory. They feel that the claim that Bacon authored Shakespeare’s poetry suffers from the fact that Bacon’s poetry is abrupt and stilted unlike Shakespeare's, and note that Shakespeare discusses legal concepts and terms far more abstractly than Bacon.[citation needed]

Christopher Marlowe

The gifted playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe has been a popular candidate even though he was apparently dead when most of the plays were written. A case for Marlowe was made as early as 1895, but the creator of the most detailed theory of Marlowe's authorship was Calvin Hoffman, an American journalist whose book on the subject, The Murder of the Man who was Shakespeare, was published in 1955.

According to history, Marlowe was killed in 1593 by a group of men including Ingram Frizer, a servant of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's patron. A theory has developed that Marlowe, who may have been facing an impending death penalty for heresy, was saved by the faking of his death (with the aid of Walsingham and Marlowe's possible employer, Lord Burghley) and that he subsequently wrote the works of Shakespeare.[63]

Supporters of Marlovian theory also point to stylometric tests and studies of parallel phraseology, which seem to prove how "both" authors used similar vocabulary and a similar style.[64].[65]

Mainstream scholars find the argument for Marlowe's faked death unconvincing. They also find the writing of Marlowe and Shakespeare very different, and attribute any similarities to the popularity and influence of Marlowe's work on subsequent dramatists such as Shakespeare.

Other candidates

Two recent candidates are Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke, Recorder of Stratford-Upon-Avon and Sir Henry Neville. According to A.W.L. Saunders in his 2007 publication, The Master of Shakespeare; Greville is unique among all candidates as he is the only one to have claimed to have been 'The master of Shakespeare'. In addition, in 1990, the Shakespeare Project; a 'word crunching' computer program created by a team of professors in California, produced results to support this claim. In The Truth Will Out, published in 2005, authors Brenda James, a part-time lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, and Professor William Rubinstein, professor of history at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, argue that Henry Neville, a contemporary Elizabethan English diplomat who was a distant relative of Shakespeare, is the true author. Neville's career placed him in the locations of many of the plays about the time they were written and that his life contains parallels with the events in the plays. Other candidates proposed include Mary Sidney; William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby; Sir Edward Dyer; or Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland (sometimes with his wife Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Philip Sidney, and her aunt Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, as co-authors). At least fifty others have also been proposed, including the Irish rebel, William Nugent, Catholic martyr St Edmund Campion;[66] and Queen Elizabeth (based on a supposed resemblance between a portrait of the Queen and the engraving of Shakespeare that appears in the First Folio). Malcolm X argued that Shakespeare was actually King James I.[67]

Carlos Fuentes raises an intriguing possibility in his book Myself With Others: Selected Essays (1988) noting that, "Cervantes leaves open the pages of a book where the reader knows himself to be written and it is said that he dies on the same date, though not on the same day, as William Shakespeare. It is further stated that perhaps both were the same man." Francis Carr proposed that Francis Bacon was Shakespeare and the author of Don Quixote.[citation needed] A 2007 film called Miguel and William, written and directed by Inés París, explores the parallels and alleged collaboration between Cervantes and Shakespeare.[68] This romantic comedy shows Shakespeare spending the years 1586 to 1592 in Madrid where he enjoys a great friendship with Cervantes.

In the 1960's, the most popular general theory was that Shakespeare's plays and poems were the work of a group rather than one individual. A group consisting of De Vere, Bacon, William Stanley, and others, has been put forward, for example. [69] This theory has been often noted, most recently by renowned actor Derek Jacobi, who told the British press "I subscribe to the group theory. I don't think anybody could do it on their own. I think the leading light was probably de Vere, as I agree that an author writes about his own experiences, his own life and personalities."[70]

See also

Further reading

Mainstream/Neutral/Questioning

- Bertram Fields, Players: The Mysterious Identity of William Shakespeare (2005)

- H. N. Gibson, The Shakespeare Claimants (London, 1962). (An overview written from an orthodox perspective).

- Greenwood, George The Shakespeare Problem Restated. (London: John Lane, 1908).

- Shakespeare's Law and Latin. (London: Watts & Co., 1916).

- Is There a Shakespeare Problem? (London: John Lane, 1916).

- Shakespeare's Law. (London: Cecil Palmer, 1920).

- E.A.J. Honigman: The Lost Years, 1985.

- John Michell, Who Wrote Shakespeare? (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999). ISBN 0-500-28113-0. (An overview from a neutral perspective).

- Irvin Leigh Matus, Shakspeare, in Fact (London: Continuum, 1999). ISBN 0-8264-0928-8. (Orthodox response to the Oxford theory).

- Ian Wilson: Shakespeare - The Evidence, 1993.

- Scott McCrea: "The Case for Shakespeare", (Westport CT: Praeger, 2005). ISBN 0-275-98527-X.

- Bob Grumman: "Shakespeare & the Rigidniks", (Port Charlotte FL: The Runaway Spoon Press, 2006). ISBN 1-57141-072-4.

Oxfordian

- Mark Anderson, "Shakespeare" By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, The Man Who Was Shakespeare (2005).

- Al Austin and Judy Woodruff, The Shakespeare Mystery, 1989 Frontline documentary. [1]. (Documentary film about the Oxford case.)

- Fowler, William Plumer Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford's Letters. (Portsmouth, New Hampshire: 1986).

- Hope, Warren and Kim Holston The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Claimants to Authorship, and their Champions and Detractors. (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 1992).

- J. Thomas Looney, Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. (London: Cecil Palmer, 1920). [2]. (The first book to promote the Oxford theory.)

- Malim, Richard (Ed.) Great Oxford: Essays on the Life and Work of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, 1550-16-4. (London: Parapress, 2004).

- Charlton Ogburn Jr., The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Man Behind the Mask. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1984). (Influential book that criticises orthodox scholarship and promotes the Oxford theory).

- Diana Price, Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of An Authorship Problem (Westport, Ct: Greenwood, 2001). [3]. (Introduction to the evidentiary problems of the orthodox tradition).

- Sobran, Joseph, Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997).

- Stritmatter, Roger The Marginalia of Edward de Vere's Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence. 2001 University of Massachusetts PhD dissertation. [4]

- Ward, B.M. The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (1550-1604) From Contemporary Documents (London: John Murray, 1928).

- Whalen, Richard Shakespeare: Who Was He? The Oxford Challenge to the Bard of Avon. (Westport, Ct.: Praeger, 1994).

Baconian

- N. Cockburn, The Bacon – Shakespeare Question, private publication 1998 (Contents) A barrister's presentation of the evidence.

- Peter Dawkins: The Shakespeare Enigma, Polair Publ., London 2004, ISBN 0-9545389-4-3 (engl.)

- Amelie Deventer von Kunow, Francis Bacon: Last of the Tudors, trans. Willard Parker (1924)

- Penn Leary, Bacon Is Shakespeare, Cryptographic Shakespeare (n.d.)

- Fellows, Virginia M., The Shakespeare Code (2006) ISBN-13: 978-1-932890-02-5.

- Baconian Evidence For Shakespeare Evidence

Rutlandian

- Karl Bleibtreu: Der Wahre Shakespeare, Munich 1907, G. Mueller

- Lewis Frederick Bostelmann: Rutland, New York 1911, Rutland publishing company

- Celestin Demblon: Lord Rutland est Shakespeare, Paris 1912, Charles Carrington

- Pierre S. Porohovshikov (Porokhovshchikov): Shakespeare Unmasked, New York 1940, Savoy book publishers

- Ilya Gililov: The Shakespeare Game: The Mystery of the Great Phoenix, New York : Algora Pub., c2003., ISBN 0-87586-182-2 , 0875861814 (pbk.)

- Brian Dutton: Let Shakspere Die: Long Live the Merry Madcap Lord Roger Manner, 5th Earl of Rutland the Real "Shakespeare", c.2007, RoseDog Books - most recent study of the Rutland theory.

Academic authorship debates

- Jonathan Hope, The Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays: A Socio-Linguistic Study (Cambridge University Press, 1994). (Concerned with the 'academic authorship debate' surrounding Shakespeare's collaborations and apocrypha, not with the false identity theories).

References and Notes

- ^ Ogburn, The Mysterious William Shakespeare, 1984, p173

- ^ National Portrait Gallery, Searching for Shakespeare, NPG Publications, 2006

- ^ McMichael, George (1962). Shakespeare and His Rivals, A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. New York: Odyssey Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gibson, H.N. (2005). The Shakespeare Claimants: A Critical Survey of the Four Principle Theories Concerning the Authorship of the Shakespearean Plays. Routledge. pp. 48, 72, 124. ISBN 0415352908.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ McMichael, George (1962). Shakespeare and His Rivals, A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. page 63: New York: Odyssey Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ McMichael, 143.

- ^ McMichael, pg159

- ^ For a detailed account of the anti-Stratfordian debate and the Oxford candidacy, see Charlton Ogburn's, "The Mystery of William Shakespeare", 1984, pgs86–88

- ^ For a full account of the documents relating to Shakespeare's life, see Samuel Schoenbaum, William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (OUP, 1987)

- ^ a b c Anderson, Mark. "Shakespeare" by Another Name. New York City: Gotham Books. pp. xxx. ISBN 1592402151.

- ^ Yahoo.com, Coalition aims to expose Shakespeare

- ^ Justice John Paul Stevens "The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction" UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW (v.140: no. 4, April 1992)

- ^ Ascham, R. The Schoolmaster

- ^ Greene, Robert, Farewell to Folly (1591)

- ^ For more accurate facsimiles, see S. Schoenbaum, William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life (New York: OUP, 1975), pp. 212, 221, 225, 243–5.

- ^ http://www.shakespeare-authorship.com/resources/literacy.asp

- ^ Thompson, Craig R. Schools in Tudor England. Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1958. It should be noted that statistical evidence compiled by David Cressy indicates that a large percentage (as much as 90%) of women may not have had enough education to sign their own names; see Friedman, Alice T. "The Influence of Humanism on the Education of Girls and Boys in Tudor England." History of Education Quarterly 24 (1985):57

- ^ S. Schoenbaum, William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life (New York: OUP, 1975), p. 234.

- ^ http://michaelprescott.freeservers.com/ShakespeareVsShakespeare.htm

- ^ Baldwin, T. W. William Shakspere's Small Latine and Less Greeke. 2 Volumes. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1944: passim. See also Whitaker, Virgil. Shakespeare's Use of Learning. San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1953: 14-44.

- ^ Germaine Greer "Past Masters: Shakespeare" (Oxford University Press 1986, ISBN 0-19-287538-8) pp1–2

- ^ Ridell, James, and Stewart, Stanley, The Ben Jonson Journal, Vol. 1 (1994), p.183; article refers to an inventory of Ben Jonson's private library

- ^ Riggs, David, Ben Jonson: A Life (Harvard University Press: 1989), p.58.

- ^ A. L. Rowse: "Shakespeare's supposed 'lost' years". Contemporary Review, Feb 1994. David Kathman, 'Shakespeare and Richard Field'. The Shakespeare Authorship Page.

- ^ Jonathan Bate, Shakespeare and Ovid (Clarendon Press, 1994)

- ^ Anderson, Mark. "Shakespeare" by Another Name. New York City: Gotham Books. ISBN 1592402151.

- ^ http://www.shaksper.net/archives/1992/0064.html

- ^ Spedding, James, The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon (1872), Vol.7, p.228-30 ("And in particular, I wish the Elogium I wrote in felicem memoriam Reginae Elizabethae may be published")

- ^ G. E. Bentley, The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare's Time: 1590–1642 (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1971)

- ^ First Folio, 1623, Epistle, A2)

- ^ http://www.shakespeare-oxford.com/?p=39

- ^ Bate, Jonathan, The Genius of Shakespeare (London, Picador, 1997)

- ^ Ogburn, The Mysterious William Shakespeare, 1984

- ^ Anderson, Shakespeare by Another Name, 2005, pgs 400–405

- ^ Karl Elze, Essays on Shakespeare, 1874, pgs 1–29, 151–192

- ^ Alfred Harbage, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, 1969

- ^ These researchers note that the words “ever-living” rarely, if ever, refer to someone who is actually alive. Miller, amended Shakespeare Identified, Volume 2, pgs 211–214

- ^ Shakespeare himself used the phrase in this context in Henry VI, part 1 (IV, iii, 51-2) describing the dead Henry V as “[t]hat ever-living man of memory”

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, 1989

- ^ Ruth Lloyd Miller, Essays, Heminges vs. Ostler, 1992.

- ^ Jonson, Discoveries 1641, ed. G. B. Harrison (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966), p. 28.

- ^ Jonson, Discoveries 1641, ed. G. B. Harrison (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966), p. 28.

- ^ Jonson's Discoveries 1641, ed. G. B. Harrison (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966), p. 29.

- ^ Dawkins, Peter, The Shakespeare Enigma (Polair: 2004), p.44

- ^ Dawkins, Peter, The Shakespeare Enigma (Polair: 2004), p.47

- ^ Davenport, Arnold, (Ed.), The Scourge of Villanie 1599, Satire III, in The Poems of John Marston (Liverpool University Press: 1961), pp.117, 300–1

- ^ See John Russell Brown, ed. The Merchant of Venice, Arden Edition, 1961, note to Act 3, Sc.4, p.96

- ^ See J.H. Pafford, ed. The Winter's Tale, Arden Edition, 1962, p. 66

- ^ A Modern Herbal: Heartsease; Warwickshire dialect is also discussed in Jonathan Bate, The Genius of Shakespeare OUP, 1998; and in Wood, M., In Search of Shakespeare, BBC Books, 2003, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Irvin Leigh Matus, Shakespeare in Fact (1994)

- ^ Gearoge McMichael, Edward M. Glenn Shakespeare and His Rivals, pg 56

- ^ John Michell "Who Wrote Shakespeare" ISBN 0-500-28113-0

- ^ Traubel, H.: With Walt Whitman in Camden, qtd. in Anon, 'Walt Whitman on Shakespeare'. The Shakespeare Fellowship. (Oxfordian website). Accessed April 16, 2006.

- ^ http://www.shakespeare-oxford.com/?p=39

- ^ Stritmatter, Roger A. The Marginalia of Edward de Vere's Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence (PhD diss., University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 2001). Partial reprint at Mark Anderson, ed. The Shakespeare Fellowship (1997–2002) (Oxfordian website). Accessed April 13, 2006.

- ^ a b Fowler, 1986

- ^ Ogburn, The Mystery of William Shakespeare, 1984, pg 703)

- ^ Sirbacon.org, Constance Pott

- ^ Bacon, Francis, Advancement of Learning 1640, Book 2, xiii

- ^ Francis Carr, Who Wrote Don Quixote? (London: Xlibris Corporation, 2004).

- ^ British Library MS Harley 7017; transcription in Durning-Lawrence, Edward, Bacon is Shakespeare (1910)

- ^ Lambeth MS 976, folio 4

- ^ Baker, John 'The Case for the [sic] Christopher Marlowe's Authorship of the Works attributed to William Shakespeare'. John Baker's New and Improved Marlowe/Shakespeare Thought Emporium (2002). Accessed 13 April, 2006.

- ^ Baker, John, 'Dr Mendenhall Proves Marlowe was the Author Shakespeare?'[sic]. John Baker's New and Improved Marlowe/Shakespeare Thought Emporium (2002). Accessed 13 April, 2006.

- ^ Baker, John 'The Case for the [sic] Christopher Marlowe's Authorship of the Works attributed to William Shakespeare'. John Baker's New and Improved Marlowe/Shakespeare Thought Emporium (2002). Accessed 13 April, 2006.

- ^ The Case for Edmund Campion

- ^ X, Malcom (1965). The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Grove Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://observer.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,,2115743,00.html Were these the Two Gentlemen of Madrid?

- ^ McMichael, pg 154

- ^ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20070908/ap_on_re_eu/britain_shakespeare_debate

External links

General Non-Stratfordian

- The Shakespeare Authorship Coalition, home of the "Declaration of Reasonable Doubt About the Identify of William Shakespeare" -- a concise, definitive explanation of the reasons to doubt the case for the Stratford man. Doubters can read, and sign, the Declaration online.

Mainstream

- David Kathman and Terry Ross, The Shakespeare Authorship Page (table of contents)

- Irvin Leigh Matus's Shakespeare Site (includes several articles defending the orthodox position)

- Irvin Leigh Matus, "The Case for Shakespeare", from Atlantic Monthly, 1991

- Truth vs. Theory Shakespeare As Autodidact

- T.L. Hubeart, Jr. "The Shakespeare Authorship Question" Brief overview of the rise of anti-Stratfordianism.

- The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust: "Shakespeare's authorship" Brief overview.

- Alan H. Nelson's Shakespeare Authorship Pages - created by a biographer of Oxford who does not believe he wrote Shakespeare

Oxfordian

- The Shakespeare Fellowship current research on the Oxfordian theory

- Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook. Archive of materials on the authorship question, especially from an Oxfordian perspective.

- Articles by Lynne Kositsky and Roger Stritmatter, challenging the methods and conclusions of Stratfordian David Kathman

- Joseph Sobran's response to David Kathman's "historical record" articles

- State of the Debate - Oxfordian vs. Stratfordian

- Shakespeare Oxford Society

- The Shakespeare Mystery (Website for a PBS documentary; includes several articles)

- Joseph Sobran, The Shakespeare Library (collection of Joseph Sobran's Oxfordian columns. Sobran's Alias Shakespeare is mentioned here, also.)

- The Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference A yearly academic conference at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon on Oxfordian theory

- The De Vere Society of Great Britain

Marlovian

- Peter Farey's Marlowe Page

- Frontline: Much Ado About Something(website for a TV documentary)

- Marlowe Lives! (collection of articles, documents and links)

- John Baker, The Case for the Christopher Marlowe's Authorship of the Works attributed to William Shakespeare

- Jeffrey Gantz, review of Hamlet, by William Shakespear and Christopher Marlowe: 400th Anniversary Edition (a sceptical review of a Marlovian book)

- Peter Bull, Shakespeare's Sonnets Written by Kit Marlowe

Other candidates

- The Master of Shakespeare, A.W.L. Saunders, 2007 Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke. Website for the book The Master of Shakespeare, 2007

- Chichester Festival Theatre I Am Shakespeare Webcam Daytime Chat-Room Show by Mark Rylance. A new production by former Artistic Director of The Globe Theatre on the Shakespeare authorship debate.

- Mary Sidney - Website for a book by Robin P. Williams on Mary Sidney's authorship

- I. Gililov, The Shakespeare Game: The Mystery of the Great Phoenix (original Russian text)

- HenryNeville.com - Website for a book on Sir Henry Neville's authorship

- The URL of Derby (promotes the Earl of Derby)

- Terry Ross, "The Droeshout Engraving of Shakespeare: Why It's NOT Queen Elizabeth".