Endangered species

| Conservation status |

|---|

| Extinct |

| Threatened |

| Lower Risk |

| Other categories |

| Related topics |

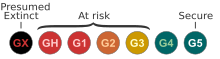

Comparison of Red List classes above and NatureServe status below  |

An endangered species is a population of an organism which is at risk of becoming extinct because it is either few in number, or threatened by changing environmental or predation parameters. An endangered species is usually a taxonomic species, but may be another evolutionary significant unit such as a subspecies. The World Conservation Union (IUCN) has calculated the percentage of endangered species as 40 percent of all organisms based on the sample of species that have been evaluated through 2006.[1] (Note: the IUCN groups all threatened species for their summary purposes.) Many nations have laws offering protection to these species: for example, forbidding hunting, restricting land development or creating preserves. Only a few of the many species at risk of extinction actually make it to the lists and obtain legal protection. Many more species become extinct, or potentially will become extinct, without gaining public notice.

The high rate at which species have become extinct within the last 150 years is a cause of concern. While species have evolved and become extinct on a regular basis for the last several hundred million years, recent rates of extinction are many times higher than the typical historical values. Significantly, the rate of species extinctions at present is estimated at 100 to 1000 times "background" or average extinction rates in the evolutionary time scale of planet Earth;[2] moreover, this current rate of extinction is thus 10 to 100 times greater than any of the prior mass extinction events in the history of the Earth. If this rate of extinction continues or accelerates, the number of species becoming extinct in the next decade could number in the millions[3]. While most people readily relate to endangerment of large mammals or birdlife, some of the greatest ecological issues are the threats to stability of whole ecosystems if key species vanish at any level of the food chain.

Issues of extinction

Four reasons for concern about extinction are:

- loss of a species as a biological entity;

- destabilization of an ecosystem;

- endangerment of other species;

- loss of irreplaceable genetic material and associated biochemicals

The loss of a species in and of itself is an important factor, both as diminution of the enjoyment of nature, and as a moral issue for those who believe humans are stewards of the natural environment (as well as some who believe that animal species have rights). Destabilization is a well understood outcome, when an element of food or predation is removed from an ecosystem. When one species goes extinct, population increases or declines often result in secondary species. An unstable spiral can ensue, until other species are lost and the ecosystem structure is changed markedly and irreversibly.

The fourth reason is more subtle, but perhaps the most important point for mankind to grasp. Each species carries unique genetic material in its DNA and may produce unique chemicals according to these genetic instructions. For example, in the valleys of central China, a fernlike weed called sweet wormwood grows, that is the only source of artemisinin, a drug that is nearly 100 percent effective against malaria (Jonietz, 2006). If this plant were lost to extinction, then the ability to control malaria, even today a potent killer, would diminish. There are countless other examples of chemicals unique to an individual species. The number of chemicals not yet discovered that could vanish from the planet when further species become extinct cannot be determined, but it is a highly debated and influential point.

Though extinction can be a natural effect of the process of natural selection, the current extinction crisis is not related to that process. At the present, the Earth has fallen from a peak of biodiversity[1] and Earth is undergoing the Holocene mass extinction period. These periods have occurred before without human intervention; however the current extinction period is unique. Previous periods were triggered by physical causes, such as impact events, tectonic plates and high volcanic activity, all leading to climate change. The current extinction period is being caused by humans and began approximately 100,000 years ago with the diaspora of humans to different parts the world. By entering new ecosystems which had never before experienced the human presence, humans disrupted the ecological balance by hunting, habitat destruction and transmitting diseases. From 100,000 years ago up to 10,000 years ago is called "phase one" of the sixth extinction period.

Phase two of the period began approximately 10,000 years ago with the birth of agriculture. With the birth of agriculture, humans did not have to rely on interaction with other species for survival and began to domesticate them; humans also did not need to adhere to a static limitation of carrying capacity. Thus, humans became the first species able to live by appreciably modifying historic ecosystems. As Niles Eldridge says, "Indeed, to develop agriculture is essentially to declare war on ecosystems - converting land to produce one or two food crops, with all other native plant species all now classified as unwanted "weeds" -- and all but a few domesticated species of animals now considered as pests." With the ability to live outside of a local ecosystem, humans have been free to breech the "carrying-capacity" of areas and overpopulate, putting ever more stress on the environment with destructive activities necessary for more population growth. Today, those activities include tropical deforestation, coral loss, other habitat destruction, overexploitation of species, introduction of alien species into ecosystems and pollution, and soil contamination and greenhouse gases).

A method of analyzing the risk of extinction for a given organism is by evaluation of Critical depensation, a measure of population biomass rate of change (actually, mathematically the second derivative).

Conservation status

The conservation status of a species is an indicator of the likelihood of that endangered species continuing to survive. Many factors are taken into account when assessing the conservation status of a species; not simply the number remaining, but the overall increase or decrease in the population over time, breeding success rates, known threats, and so on. The IUCN Red List is the best known conservation status listing.

Internationally, 189 countries have signed an accord agreeing to create Biodiversity Action Plans to protect endangered and other threatened species. In the USA this plan is usually called a species Recovery Plan.

IUCN Red List Endangered species

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species uses the term endangered species as a specific category of imperilment, rather than as a general term. Under the IUCN Categories and Criteria, endangered species is between critically endangered and vulnerable. Also critically endangered species may also be counted as endangered species and fill all the criteria.

The more general term used by the IUCN for species at risk of extinction is threatened species, which also includes the less-at-risk category of vulnerable species together with endangered and critically endangered.

IUCN categories include:

- Extinct: the last remaining member of the species had died, or is presumed beyond reasonable doubt to have died. Examples: Thylacine, Dodo, Passenger Pigeon

- Extinct in the wild: captive individuals survive, but there is no free-living, natural population. Examples: Alagoas Curassow

- Critically endangered: faces an extremely high risk of extinction in the immediate future. Examples: Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Arakan Forest Turtle, Javan Rhino

- Endangered: faces a very high risk of extinction in the near future. Examples: Cheetah, Blue Whale, Snow Leopard, African Wild Dog

- Vulnerable: faces a high risk of extinction in the medium-term. Examples: Gaur, Lion

- Least Concern: no immediate threat to the survival of the species. Examples: Norway Rat, Nootka Cypress

United States

Under the Endangered Species Act in the United States, "endangered" is the more protected the two protected categories. The Salt Creek tiger beetle (Cicindela nevadica lincolniana) is an example of a endangered subspecies protected under the ESA.

Controversy

Some endangered species laws are controversial. Typical areas of controversy include: criteria for placing a species on the endangered species list, and criteria for removing a species from the list once its population has recovered; whether restrictions on land development constitute a "taking" of land by the government; the related question of whether private landowners should be compensated for the loss of use of their land; and obtaining reasonable exceptions to protection laws.

Being listed as an endangered species can have negative effect since it could make a species more desirable for collectors and poachers.[4] This effect is potentially reduce-able, such as in China where commercially farmed turtles may be reducing some of the pressure to poach endangered species. [5]

Another problem with listing species is its effect of inciting the use of the "shoot, shovel, and shut up" method of clearing endangered species from an area of land. Some landowners currently may perceive a diminution in value for their land after finding an endangered animal on it. They have allegedly opted to silently kill and bury the animals or destroy habitat, thus removing the problem from their land, but at the same time further reducing the population of an endangered species. [6] It has also been noted that the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act itself, which coined the term "endangered species", has been questioned by business advocacy groups and their publications, but is nevertheless widely recognized as an effective recovery tool by wildlife scientists who work with the species. To date 19 species have been delisted and recovered [2][7], although 93% of species listed now have a recovering or at least stable population.

Gallery

-

The endangered Island Fox

-

The endangered Sea Otter

-

American bison skull heap. There were as few as 750 bison in 1890 from overhunting.

-

Immature California Condor

-

Loggerhead Sea Turtle

-

Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander (photo courtesy of Don Roberson)

-

An Asian arowana

See also

- Conservation status

- Red and Blue-listed

- IUCN Red List

- African Wild Dog Conservancy

- Gene pool

- World Conservation Union (IUCN)

- Wildlife conservation

- in-situ conservation

- Ex-situ conservation

- Biodiversity

- Convention on Biological Diversity

- Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES)

- Extinct birds

- Endangered Species Act

- Birds Directive (EU's bird conservation directive)

- Habitats Directive (EU's wildlife and nature conservation directive)

- International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling

- List of endangered animal species

- List of extinct animals

- List of endangered species in the British Isles

- Rare species

- Red Data Book of the Russian Federation

- Snail darter controversy

- Timeline of environmental events

- Ecological Economics

- Reintroduction

- Wildlife Enforcement Monitoring System (WEMS)

- CITES

- Extinction

- List of Conservation topics

Notes

- ^ IUCN Red-list statistics (2006)

- ^ J.H.Lawton and R.M.May, Extinction rates, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- ^ S.L. Pimm, G.J. Russell, J.L. Gittleman and T.M. Brooks, The Future of Biodiversity, Science 269: 347-350 (1915)

- ^ Courchamp, Franck. "Rarity Value and Species Extinction: The Anthropogenic Allee Effect". PLoS Biology. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dharmananda, Subhuti. "Endangered Species issues affecting turtles and tortoises used in Chinese medicine". Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bailey, Ronald (2003-12-31). ""Shoot, Shovel and Shut Up"" (html). Reasononline. Reason Magazine. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ "U.S. Endangered Species Act" (html). Environmental Literacy Counsel. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- The World Conservation Union (IUCN)

- The Convention on Biological Diversity

- Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, IUCN

- The World Wide Fund for Nature

- African Wild Dog Conservancy

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Threatened and Endangered Species System (TESS).

- Endangered Species & Wetlands Report Independent print and online newsletter covering the ESA, wetlands and regulatory takings.

- Endangered species by continent

- Sundarbans Tiger Project Research and Conservation of tigers in the largest remaining mangrove forest in the world.

- Everything you wanted to know about endangered species — Provided by New Scientist.

- "Science counts species on brink". (Nov 17, 2004). BBC News.

- Endangered Native Carnivores in the Southern Rockies

- "Biodiversity and Conservation: A Hypertext Book by Peter J. Bryant

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Endangered Species

- Endangered Species Information

- CBC Digital Archives – Endangered Species in Canada

- Bagheera website on endangered species

- ONLINE BOOK: “In situ conservation of livestock and poultry”, 1983, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Environment Programme

- 100 Success Stories for Endangered Species Act

- The Red List