Hanbok: Difference between revisions

Reverted 5 edits by Hlovekorean , go to the talk page |

Hlovekorean (talk | contribs) Restored recent history of Hanbok : Dispute over history, China’s Northeast Asia Project, Controversy over distortion of hanbok in China |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

[[File:Hanbok accessories.jpg|thumb|{{lang|ko-Latn|Hanbok}} accessories]] |

[[File:Hanbok accessories.jpg|thumb|{{lang|ko-Latn|Hanbok}} accessories]] |

||

[[File:Children dressed in Korean traditional clothing at the opening ceremony for Old Korean Legation - 2018 (42300672731).jpg|thumb|Children in [[Washington DC]] wearing {{lang|ko-Latn|hanbok}}]] |

[[File:Children dressed in Korean traditional clothing at the opening ceremony for Old Korean Legation - 2018 (42300672731).jpg|thumb|Children in [[Washington DC]] wearing {{lang|ko-Latn|hanbok}}]] |

||

The '''{{lang|ko-Latn|hanbok}}''' (in [[South Korean standard language|South Korea]]) or '''{{lang|ko-Latn|Chosŏn-ot}}''' (in [[North Korean standard language|North Korea]]) is the traditional Korean clothes. The term "Hanbok" literally means "Korean clothing". It was established as a part of the unique living culture of Korea, influenced by the geographical and climatic nature of the Korea, and handed down throughout the years to present times.<ref>Korean Culture and Information Service, 2018, Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea</ref> |

The '''{{lang|ko-Latn|hanbok}}''' (in [[South Korean standard language|South Korea]]) or '''{{lang|ko-Latn|Chosŏn-ot}}''' (in [[North Korean standard language|North Korea]]) is the traditional Korean clothes. The term "Hanbok" literally means "Korean clothing". It was established as a part of the unique living culture of Korea, influenced by the geographical and climatic nature of the Korea, and handed down throughout the years to present times.<ref>Korean Culture and Information Service, 2018, Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea</ref> |

||

Hanbok is characterized by its wrapped front top, long, high waisted skirt and its typically vibrant colours. Two piece clothing style of Hanbok is closer to the style of the nomadic tribes.<ref>역사 속의 우리 옷 변천사, 2009, Chonnam National University Press</ref> |

Hanbok is characterized by its wrapped front top, long, high waisted skirt and its typically vibrant colours. Two piece clothing style of Hanbok is closer to the style of the nomadic tribes.<ref>역사 속의 우리 옷 변천사, 2009, Chonnam National University Press</ref> |

||

Hanbok can be traced back to the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea]] period ( |

Hanbok can be traced back to the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea]] period (1st century BC ~ 7th century AD), with roots in the peoples of what is now northern Korea and Manchuria. Early forms of Hanbok can be seen in the art of [[Goguryeo]] tomb murals in the same period. The earliest ones can be found in mural paintings dating from the 5th century.<ref>The Dreams of the Living and the Hopes of the Dead-Goguryeo Tomb Murals, 2007, Ho-Tae Jeon, Seoul National University Press</ref> |

||

From this time, the basic structure of hanbok, namely the jeogori jacket, baji pants, and the chima skirt, were already established. Short, tight trousers and tight, waist-length jackets were worn by both men and women during the early years of the Three Kingdoms of Korea period. The basic structure and these basic design features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day. |

From this time, the basic structure of hanbok, namely the jeogori jacket, baji pants, and the chima skirt, were already established. Short, tight trousers and tight, waist-length jackets were worn by both men and women during the early years of the Three Kingdoms of Korea period. The basic structure and these basic design features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day. |

||

In the modern day, {{lang|ko-Latn|"hanbok"}} usually refers specifically to the clothing worn and developed during the {{lang|ko-Latn|[[Joseon]]|italic=no}} dynasty period by the upper classes. In general, the clothing of Korea's rulers and aristocrats was influenced by both foreign and [[Indigenous peoples|indigenous]] styles, resulting in some styles of clothing, such as the [[Shenyi|''simui'']] from China's Song Dynasty, {{lang|ko-Latn|[[gwanbok]]}} worn by male officials and Court clothing of women in the court and women of royalty were adapted from the clothing style of China's [[Ming dynasty|Ming]] dynasties.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156808055|title=The Greenwood encyclopedia of clothing through world history|date=2008|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-33662-1|location=Westport, Connecticut|oclc=156808055}}</ref><ref>McCallion, 2008, p. 221 - 228</ref> The cultural exchange was also bilateral and [[Goryeo]] hanbok had cultural influence on the [[Yuan dynasty]].<ref>고려(高麗)의 원(元)에 대(對)한 공녀(貢女),유홍렬,震檀學報,1957</ref> |

In the modern day, {{lang|ko-Latn|"hanbok"}} usually refers specifically to the clothing worn and developed during the {{lang|ko-Latn|[[Joseon]]|italic=no}} dynasty period by the upper classes. In general, the clothing of Korea's rulers and aristocrats was influenced by both foreign and [[Indigenous peoples|indigenous]] styles, resulting in some styles of clothing, such as the [[Shenyi|''simui'']] from China's Song Dynasty, {{lang|ko-Latn|[[gwanbok]]}} worn by male officials and Court clothing of women in the court and women of royalty were adapted from the clothing style of China's [[Ming dynasty|Ming]] dynasties.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156808055|title=The Greenwood encyclopedia of clothing through world history|date=2008|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-33662-1|location=Westport, Connecticut|oclc=156808055}}</ref><ref>McCallion, 2008, p. 221 - 228</ref> The cultural exchange was also bilateral and [[Goryeo]] hanbok had cultural influence on the [[Yuan dynasty]].<ref>고려(高麗)의 원(元)에 대(對)한 공녀(貢女),유홍렬,震檀學報,1957</ref> |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

The form of ''Jeogori'' has changed over time.<ref name="Britannica" /> While men's ''jeogori'' remained relatively unchanged, women's ''jeogori'' dramatically shortened during the Joseon dynasty, reaching its shortest length at the late 19th century. However, due to reformation efforts and practical reasons, modern ''jeogori'' for women is longer than its earlier counterpart. Nonetheless the length is still above the waistline. Traditionally, ''goreum'' were short and narrow, however modern ''goreum'' are rather long and wide. There are several types of ''jeogori'' varying in fabric, sewing technique, and shape.<ref name="Britannica" /><ref name="Jeogori Reborns with New Visions of a Thousand" /> |

The form of ''Jeogori'' has changed over time.<ref name="Britannica" /> While men's ''jeogori'' remained relatively unchanged, women's ''jeogori'' dramatically shortened during the Joseon dynasty, reaching its shortest length at the late 19th century. However, due to reformation efforts and practical reasons, modern ''jeogori'' for women is longer than its earlier counterpart. Nonetheless the length is still above the waistline. Traditionally, ''goreum'' were short and narrow, however modern ''goreum'' are rather long and wide. There are several types of ''jeogori'' varying in fabric, sewing technique, and shape.<ref name="Britannica" /><ref name="Jeogori Reborns with New Visions of a Thousand" /> |

||

===Chima=== |

===Chima=== |

||

''Chima'' refers to "skirt," which is also called ''sang'' ({{linktext|裳}}) or ''gun'' ({{linktext|裙}}) in [[hanja]].<ref name="EncyKorea">{{cite web|url=http://100.empas.com/dicsearch/pentry.html?s=K&i=268156&v=45 |script-title=ko:치마 |publisher=[[Nate (web portal)|Nate]] / [[Encyclopedia of Korean Culture|EncyKorea]] |language=ko}}</ref><ref name="Doosan" /><ref name="Britannica">{{cite web|url=http://100.empas.com/dicsearch/pentry.html?s=B&i=191326&v=45 |script-title=ko:치마 |publisher=[[Nate (web portal)|Nate]] / [[Britannica]] |language=ko}}</ref> The underskirt, or [[petticoat]] layer, is called ''sokchima''. According to ancient murals of [[Goguryeo]] and an earthen toy excavated from the neighborhood of [[Hwangnam-dong]], [[Gyeongju]], Goguryeo women wore a ''chima'' with ''jeogori'' over it, covering the belt.<ref name="Koreana">{{cite journal |url=http://eng.actakoreana.org/clickkorea/text/13-Clothing/13-95aut-charateristics.html |title=Characteristics of the Korean Costume and Its Development |author=Cho, Woo-hyun |publisher=Koreana |volume=9 |issue=3 }}{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref name="Hanstyle">{{cite web |url=http://www.han-style.com/hanbok/history/hanbok_style.jsp |script-title=ko:유행과 우리옷 |trans-title=Fashion and Korean clothing |publisher=Korea the sense |language=ko |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120302181258/http://www.han-style.com/hanbok/history/hanbok_style.jsp |archive-date=2012-03-02 }}</ref> |

''Chima'' refers to "skirt," which is also called ''sang'' ({{linktext|裳}}) or ''gun'' ({{linktext|裙}}) in [[hanja]].<ref name="EncyKorea">{{cite web|url=http://100.empas.com/dicsearch/pentry.html?s=K&i=268156&v=45 |script-title=ko:치마 |publisher=[[Nate (web portal)|Nate]] / [[Encyclopedia of Korean Culture|EncyKorea]] |language=ko}}</ref><ref name="Doosan" /><ref name="Britannica">{{cite web|url=http://100.empas.com/dicsearch/pentry.html?s=B&i=191326&v=45 |script-title=ko:치마 |publisher=[[Nate (web portal)|Nate]] / [[Britannica]] |language=ko}}</ref> The underskirt, or [[petticoat]] layer, is called ''sokchima''. According to ancient murals of [[Goguryeo]] and an earthen toy excavated from the neighborhood of [[Hwangnam-dong]], [[Gyeongju]], Goguryeo women wore a ''chima'' with ''jeogori'' over it, covering the belt.<ref name="Koreana">{{cite journal |url=http://eng.actakoreana.org/clickkorea/text/13-Clothing/13-95aut-charateristics.html |title=Characteristics of the Korean Costume and Its Development |author=Cho, Woo-hyun |publisher=Koreana |volume=9 |issue=3 }}{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref name="Hanstyle">{{cite web |url=http://www.han-style.com/hanbok/history/hanbok_style.jsp |script-title=ko:유행과 우리옷 |trans-title=Fashion and Korean clothing |publisher=Korea the sense |language=ko |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120302181258/http://www.han-style.com/hanbok/history/hanbok_style.jsp |archive-date=2012-03-02 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 86: | Line 87: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===Antiquity=== |

===Antiquity=== |

||

The hanbok can be traced back to the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea]] period (57 BC to 668 AD).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Myeong-Jong |first1=Yoo |title=The Discovery of Korea: History-Nature-Cultural Heritages-Art-Tradition-Cities |date=2005 |publisher=Discovery Media |isbn=978-8995609101 |page=123}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Macdonald |editor1-first=Fiona |title=Peoples of Eastern Asia |date=2004 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |isbn=9780761475545 |page=366 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-ZuImINv0soC&pg=PA366 |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref><ref name=":8">{{cite book |last1=Lee |first1=Samuel Songhoon |title=Hanbok: Timeless Fashion Tradition |date=2015 |publisher=Seoul Selection |isbn=9781624120565 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-F01CwAAQBAJ |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref><ref name="KCIS">{{cite book |last1=Korean Culture and Information Service (South Korea) |title=Guide to Korean Culture: Korea's cultural heritage |date=2014 |publisher=길잡이미디어 |isbn=9788973755714 |page=90 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoxoBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA90 |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref> The origin of ancient hanbok can be found in the ancient clothing of what is now today's Northern Korea and [[Manchuria]];<ref name="Greenwood">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8bTzilz1BMC&pg=PA223|title=The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Volume II|date=2008|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=9780313336645|editor1-last=Condra|editor1-first=Jill|page=223|access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref> the ancient hanbok shared similarities with the clothing of the nomadic culture, hobok, through the ancient Korean's cultural exchange with the northern nomads of [[Scythians|Scythai]].<ref name="한국의상디자인학회지">{{cite journal|journal=한국의상디자인학회지|volume=20( 1)|pages=61–77|doi=10.30751/kfcda.2018.20.1.61|doi-access=free|title=Scythai's clothing type and style: Focusing on the relationship with ancient Korea|year=2018|last1=김소희|last2=채금석}}</ref> Despite Scythai's influence, the ancient hanbok of ancient Korea which consists of today's Manchuria and Northern Korea was distinct from Scythai's clothing.<ref name="한국의상디자인학회지" /> Early forms of Hanbok can be seen in the art of [[Goguryeo tombs|Goguryeo tomb]] murals in the same period from the 6th century AD.<ref name="KCIS"/><ref name="Greenwood"/><ref name="한국의상디자인학회지"/><ref>Nelson, 1993, p.7 & p.213-214</ref> |

The hanbok can be traced back to the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea]] period (57 BC to 668 AD).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Myeong-Jong |first1=Yoo |title=The Discovery of Korea: History-Nature-Cultural Heritages-Art-Tradition-Cities |date=2005 |publisher=Discovery Media |isbn=978-8995609101 |page=123}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Macdonald |editor1-first=Fiona |title=Peoples of Eastern Asia |date=2004 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |isbn=9780761475545 |page=366 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-ZuImINv0soC&pg=PA366 |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref><ref name=":8">{{cite book |last1=Lee |first1=Samuel Songhoon |title=Hanbok: Timeless Fashion Tradition |date=2015 |publisher=Seoul Selection |isbn=9781624120565 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-F01CwAAQBAJ |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref><ref name="KCIS">{{cite book |last1=Korean Culture and Information Service (South Korea) |title=Guide to Korean Culture: Korea's cultural heritage |date=2014 |publisher=길잡이미디어 |isbn=9788973755714 |page=90 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoxoBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA90 |access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref> The origin of ancient hanbok can be found in the ancient clothing of what is now today's Northern Korea and [[Manchuria]];<ref name="Greenwood">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8bTzilz1BMC&pg=PA223|title=The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Volume II|date=2008|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=9780313336645|editor1-last=Condra|editor1-first=Jill|page=223|access-date=18 October 2019}}</ref> the ancient hanbok shared similarities with the clothing of the nomadic culture, hobok, through the ancient Korean's cultural exchange with the northern nomads of [[Scythians|Scythai]].<ref name="한국의상디자인학회지">{{cite journal|journal=한국의상디자인학회지|volume=20( 1)|pages=61–77|doi=10.30751/kfcda.2018.20.1.61|doi-access=free|title=Scythai's clothing type and style: Focusing on the relationship with ancient Korea|year=2018|last1=김소희|last2=채금석}}</ref> Despite Scythai's influence, the ancient hanbok of ancient Korea which consists of today's Manchuria and Northern Korea was distinct from Scythai's clothing.<ref name="한국의상디자인학회지" /> Early forms of Hanbok can be seen in the art of [[Goguryeo tombs|Goguryeo tomb]] murals in the same period from the 6th century AD.<ref name="KCIS"/><ref name="Greenwood"/><ref name="한국의상디자인학회지"/><ref>Nelson, 1993, p.7 & p.213-214</ref> |

||

From this time, the basic structure of hanbok, namely the ''[[jeogori]]'' jacket, ''[[Baji (clothing)|baji]]'' pants, and the long, ''[[Chima (clothing)|chima]]'' skirt, were already established. Short, tight trousers and tight, waist-length jackets, ''twii'' (a sash-like belt) were worn by both men and women during the early years of the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea|Three Kingdoms of Korea period]].<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":15">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/843418851|title=Encyclopedia of national dress : traditional clothing around the world|date=2013|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-37637-5|location=Santa Barbara, Calif.|pages=409|oclc=843418851}}</ref> Women also wore ''baji'' under their ''chima''<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":15" /> The basic structure and these basic design features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.korea.net/news/News/LangView.asp?serial_no=20081111006 |title=The beauty of Korean tradition - Hanbok |author=Korea Tourism Organization |author-link=Korea Tourism Organization |date=November 20, 2008 |publisher=Korea.net}}</ref> except for the length and the ways the ''jeogori'' opening was folded as over the years, there were changes.<ref name=":8" /> Originally the ''jeogori'' opening was closed at the central front of the clothing, similar to a [[kaftan]]; the fold opening later changed to the left before eventually closing to the right side.<ref name=":8" /> Since the sixth century AD, the closing of the ''jeogori'' at the right became a standard practice.<ref name=":8" /> The length of the female ''jeogori'' also varied throughout time.<ref name=":8" /> For example, women's ''jeogori'' which are seen in Goguryeo paintings which date to the late fifth century AD are depicted shorter in length than the man's ''jeogori''.<ref name=":8" /> |

From this time, the basic structure of hanbok, namely the ''[[jeogori]]'' jacket, ''[[Baji (clothing)|baji]]'' pants, and the long, ''[[Chima (clothing)|chima]]'' skirt, were already established. Short, tight trousers and tight, waist-length jackets, ''twii'' (a sash-like belt) were worn by both men and women during the early years of the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea|Three Kingdoms of Korea period]].<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":15">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/843418851|title=Encyclopedia of national dress : traditional clothing around the world|date=2013|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-37637-5|location=Santa Barbara, Calif.|pages=409|oclc=843418851}}</ref> Women also wore ''baji'' under their ''chima''<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":15" /> The basic structure and these basic design features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.korea.net/news/News/LangView.asp?serial_no=20081111006 |title=The beauty of Korean tradition - Hanbok |author=Korea Tourism Organization |author-link=Korea Tourism Organization |date=November 20, 2008 |publisher=Korea.net}}</ref> except for the length and the ways the ''jeogori'' opening was folded as over the years, there were changes.<ref name=":8" /> Originally the ''jeogori'' opening was closed at the central front of the clothing, similar to a [[kaftan]]; the fold opening later changed to the left before eventually closing to the right side.<ref name=":8" /> Since the sixth century AD, the closing of the ''jeogori'' at the right became a standard practice.<ref name=":8" /> The length of the female ''jeogori'' also varied throughout time.<ref name=":8" /> For example, women's ''jeogori'' which are seen in Goguryeo paintings which date to the late fifth century AD are depicted shorter in length than the man's ''jeogori''.<ref name=":8" /> |

||

| Line 105: | Line 106: | ||

==== United Silla ==== |

==== United Silla ==== |

||

The [[Silla]] Kingdom unified the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea|Three Kingdoms]] in 668 AD. The [[Later Silla|Unified Silla]] (668-935 AD) was the golden age of Korea. In Unified Silla, various silks, linens, and fashions were imported from [[Tang dynasty|Tang]] China and Persia.<ref name=":8" /> In the process, the latest fashions trend of [[Luoyang]] which included Chinese dress styles, the second capital of Tang, were also introduced to Korea, where the Korean silhouette became similar to the Western [[Empire silhouette]]. Under the influence of China's [[Tang dynasty]], aristocratic women in United Silla started to wear their skirts over their jackets, which is a distinctive dress style worn by the women of the [[Tang dynasty]].<ref name=":8" /> King [[Muyeol of Silla]] personally travelled to the [[Tang dynasty]] to voluntarily request for clothes and belts; it is however difficult to determine which specific form and type of clothing was bestowed although Silla requested the bokdu (幞頭; a form of hempen hood during this period), danryunpo (團領袍; round collar gown), [[banbi]], baedang (䘯襠), and pyo (褾).<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last1=Yu|first1=Ju-Ri|last2=Kim|first2=Jeong-Mee|date=2006|title=A Study on Costume Culture Interchange Resulting from Political Factors|journal=Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles|volume=30|issue=3|pages=458–469}}</ref> Based on archeological findings, it is assumed that the clothing which was brought back during Queen Jindeok rule are ''danryunpo'' and ''bokdu''.<ref name=":2" /> The bokdu also become part of the official dress code of royal aristocrats, court musicians, servants, and slaves during the reign of [[Jindeok of Silla|Queen Jindeok]]; it continued to be used throughout the Goryeo dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|last=National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/846696816|title=Gat : traditional headgear in Korea|date=2013|publisher=길잡이미디어|others=Hyŏng-bak Pak, Eunhee Hwang, Kungnip Munhwajae Yŏn'guso|isbn=978-89-6325-987-1|location=Daejeon, Korea|oclc=846696816}}</ref> In 664 AD, [[Munmu of Silla]] decreed that the costume of the queen should resemble the costume of the [[Tang dynasty]]; and thus, women's costume also accepted the costume culture of the [[Tang dynasty]].<ref name=":2" /> Women also sought to imitate the clothing of the Tang dynasty through the adoption of shoulder straps attached to their skirts and wore the skirts over the ''jeogori''.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite book|last=Lee|first=Samuel Songhoon.|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/871061483|title=Hanbok : Timeless fashion tradition|isbn=978-89-97639-41-0|oclc=871061483}}</ref> The influence of the Tang dynasty was very strong and the Tang court dress regulations were adopted in the Silla court.<ref name=":15" /><ref name=":9">{{Cite book|last=Pratt|first=Keith L.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/42675362|title=Korea : a historical and cultural dictionary|date=1999|publisher=Curzon Press|others=Richard Rutt, James Hoare|isbn=978-0-7007-0464-4|location=Richmond, Surrey|pages=106|oclc=42675362}}</ref> |

The [[Silla]] Kingdom unified the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea|Three Kingdoms]] in 668 AD. The [[Later Silla|Unified Silla]] (668-935 AD) was the golden age of Korea. In Unified Silla, various silks, linens, and fashions were imported from [[Tang dynasty|Tang]] China and Persia.<ref name=":8" /> In the process, the latest fashions trend of [[Luoyang]] which included Chinese dress styles, the second capital of Tang, were also introduced to Korea, where the Korean silhouette became similar to the Western [[Empire silhouette]]. Under the influence of China's [[Tang dynasty]], aristocratic women in United Silla started to wear their skirts over their jackets, which is a distinctive dress style worn by the women of the [[Tang dynasty]].<ref name=":8" /> King [[Muyeol of Silla]] personally travelled to the [[Tang dynasty]] to voluntarily request for clothes and belts; it is however difficult to determine which specific form and type of clothing was bestowed although Silla requested the bokdu (幞頭; a form of hempen hood during this period), danryunpo (團領袍; round collar gown), [[banbi]], baedang (䘯襠), and pyo (褾).<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last1=Yu|first1=Ju-Ri|last2=Kim|first2=Jeong-Mee|date=2006|title=A Study on Costume Culture Interchange Resulting from Political Factors|journal=Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles|volume=30|issue=3|pages=458–469}}</ref> Based on archeological findings, it is assumed that the clothing which was brought back during Queen Jindeok rule are ''danryunpo'' and ''bokdu''.<ref name=":2" /> The bokdu also become part of the official dress code of royal aristocrats, court musicians, servants, and slaves during the reign of [[Jindeok of Silla|Queen Jindeok]]; it continued to be used throughout the Goryeo dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|last=National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/846696816|title=Gat : traditional headgear in Korea|date=2013|publisher=길잡이미디어|others=Hyŏng-bak Pak, Eunhee Hwang, Kungnip Munhwajae Yŏn'guso|isbn=978-89-6325-987-1|location=Daejeon, Korea|oclc=846696816}}</ref> In 664 AD, [[Munmu of Silla]] decreed that the costume of the queen should resemble the costume of the [[Tang dynasty]]; and thus, women's costume also accepted the costume culture of the [[Tang dynasty]].<ref name=":2" /> Women also sought to imitate the clothing of the Tang dynasty through the adoption of shoulder straps attached to their skirts and wore the skirts over the ''jeogori''.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite book|last=Lee|first=Samuel Songhoon.|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/871061483|title=Hanbok : Timeless fashion tradition|isbn=978-89-97639-41-0|oclc=871061483}}</ref> The influence of the Tang dynasty was very strong and the Tang court dress regulations were adopted in the Silla court.<ref name=":15" /><ref name=":9">{{Cite book|last=Pratt|first=Keith L.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/42675362|title=Korea : a historical and cultural dictionary|date=1999|publisher=Curzon Press|others=Richard Rutt, James Hoare|isbn=978-0-7007-0464-4|location=Richmond, Surrey|pages=106|oclc=42675362}}</ref> |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

| Line 126: | Line 127: | ||

==== Goryeo ==== |

==== Goryeo ==== |

||

The Chinese style imported in the Northern-South period, however, did not affect hanbok still used by the commoners, and due to its extravagance, [[Heungdeok of Silla|King Heundeog]] enforced clothing prohibition during the year 834 AD.<ref name=":2" /> In the following Goryeo period, use of the Chinese Tang dynasty style of wearing the skirt over the top faded, and the wearing of top over skirt was revived in the aristocrat class.<ref name="Koreana" /><ref name="Hanstyle" /> |

The Chinese style imported in the Northern-South period, however, did not affect hanbok still used by the commoners, and due to its extravagance, [[Heungdeok of Silla|King Heundeog]] enforced clothing prohibition during the year 834 AD.<ref name=":2" /> In the following Goryeo period, use of the Chinese Tang dynasty style of wearing the skirt over the top faded, and the wearing of top over skirt was revived in the aristocrat class.<ref name="Koreana" /><ref name="Hanstyle" /> Instead, the clothing and headwear of royalty and nobles typically followed the clothing system of the [[Song dynasty]]; the Song dynasty clothing worn by royalty and aristocrats (possibly the painting donors) are typically depicted in the Buddhist painting of Goryeo.<ref name=":7">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1154853080|title=A companion to Korean art|date=2020|others=J. P. Park, Burglind Jungmann, Juhyung Rhi|isbn=978-1-118-92702-1|location=Hoboken, NJ|pages=192|oclc=1154853080}}</ref> The Goryeo painting "Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara", for example, is a buddhist painting which was derived from both Chinese and Central Asian pictorial references.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/38831761|title=Arts of Korea|date=1998|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art|others=Yang-mo Chŏng, Judith G. Smith, Metropolitan Museum of Art|isbn=0-87099-850-1|location=New York|pages=436|oclc=38831761}}</ref> On the other hand, the Chinese clothing worn in [[Yuan dynasty]] rarely appeared in paintings of Goryeo.<ref name=":7" /> |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (detailed view of patrons).jpg|Details of the ''Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara'' painting shows a group of nobles (possibly the donors) dress in court clothing, Goryeo painting.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/38831761|title=Arts of Korea|date=1998|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art|others=Yang-mo Chŏng, Judith G. Smith, Metropolitan Museum of Art|isbn=0-87099-850-1|location=New York|pages=435-436|oclc=38831761}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Goryeo lady joban.jpg|Portrait of Lady Jo ban (1341-1401 AD), Goryeo dynasty. |

File:Goryeo lady joban.jpg|Portrait of Lady Jo ban (1341-1401 AD), Goryeo dynasty. |

||

File:밀양고법리박익벽화묘1.jpg|Mural tomb of Bak Ik in Gobeop-ri, Miryang. Bak Ik was a civil official who lived from 1332-1398 AD. |

File:밀양고법리박익벽화묘1.jpg|Mural tomb of Bak Ik in Gobeop-ri, Miryang. Bak Ik was a civil official who lived from 1332-1398 AD. |

||

File:Korea-National.Treasure-110-Yi.Jehyung-portrait-NMK.jpg|Portrait of Yi Je-hyeon (1287–1367 AD) of the Goryeo dynasty, wearing [[Shenyi|simui]]. |

File:Korea-National.Treasure-110-Yi.Jehyung-portrait-NMK.jpg|Portrait of Yi Je-hyeon (1287–1367 AD) of the Goryeo dynasty, wearing [[Shenyi|simui]]. |

||

</gallery>Hanbok went through significant changes under Mongol rule. After the [[Goryeo]] dynasty signed a peace treaty with the [[Mongol Empire]] in the 13th century, Mongolian princesses who married into the Korean royal house brought with them Mongolian fashion which began to prevail in both formal and private life.<ref name=":2" /><ref name="Lee, Kyung-Ja, 2003">Lee, Kyung-Ja, 2003</ref><ref name="koreanculture.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.koreanculture.org/06about_korea/symbols/01hanbok.htm |title=Hanbok |publisher=Korean Overseas Information Service}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://uriculture.com/s_menu.html?menu_mcat=100540&menu_cat=100001&img_num=sub1|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110717173525/http://uriculture.com/s_menu.html?menu_mcat=100540&menu_cat=100001&img_num=sub1|url-status=dead|archive-date=17 July 2011|title=UriCulture.com|access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref> A total of seven women from the Yuan imperial family were married to the Kings of Goryeo.<ref name=":0" /> The [[Yuan dynasty]] princess followed the Mongol lifestyle who was instructed to not abandon the Yuan traditions in regards to clothings and precedents.<ref name=":2" /> As a consequence, the clothing of Yuan was worn in the Goryeo court and impacted the clothing worn by the upper class families who visited the Goryeo court.<ref name=":2" /> The Yuan clothing culture which influenced the upper classes and in some extent the general public is called ''Mongolpung''.<ref name=":0" /> King Chungryeol, who was political hostage to the [[Yuan dynasty]] and pro-Yuan, married the princess of Yuan announcing a royal edict to change into Mongol clothing.<ref name=":2" /> After the fall of the [[Yuan dynasty]], only Mongol clothing which were beneficial and suitable to Goryeo culture were maintained while the others disappeared.<ref name=":2" /> As a result of the Mongol influence, the ''chima'' skirt was shortened, and ''jeogori'' was hiked up above the waist and tied at the chest with a long, wide ribbon, the ''goruem'' (an extending ribbon tied on the right side) instead of the ''twii'' (i.e. the early sash-like belt) and the sleeves were curved slightly.{{Citation needed|date=May 2021}} |

</gallery>Hanbok went through significant changes under Mongol rule. After the [[Goryeo]] dynasty signed a peace treaty with the [[Mongol Empire]] in the 13th century, Mongolian princesses who married into the Korean royal house brought with them Mongolian fashion which began to prevail in both formal and private life.<ref name=":2" /><ref name="Lee, Kyung-Ja, 2003">Lee, Kyung-Ja, 2003</ref><ref name="koreanculture.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.koreanculture.org/06about_korea/symbols/01hanbok.htm |title=Hanbok |publisher=Korean Overseas Information Service}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://uriculture.com/s_menu.html?menu_mcat=100540&menu_cat=100001&img_num=sub1|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110717173525/http://uriculture.com/s_menu.html?menu_mcat=100540&menu_cat=100001&img_num=sub1|url-status=dead|archive-date=17 July 2011|title=UriCulture.com|access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref> A total of seven women from the Yuan imperial family were married to the Kings of Goryeo.<ref name=":0" /> The [[Yuan dynasty]] princess followed the Mongol lifestyle who was instructed to not abandon the Yuan traditions in regards to clothings and precedents.<ref name=":2" /> As a consequence, the clothing of Yuan was worn in the Goryeo court and impacted the clothing worn by the upper class families who visited the Goryeo court.<ref name=":2" /> The Yuan clothing culture which influenced the upper classes and in some extent the general public is called ''Mongolpung''.<ref name=":0" /> King Chungryeol, who was political hostage to the [[Yuan dynasty]] and pro-Yuan, married the princess of Yuan announcing a royal edict to change into Mongol clothing.<ref name=":2" /> After the fall of the [[Yuan dynasty]], only Mongol clothing which were beneficial and suitable to Goryeo culture were maintained while the others disappeared.<ref name=":2" /> As a result of the Mongol influence, the ''chima'' skirt was shortened, and ''jeogori'' was hiked up above the waist and tied at the chest with a long, wide ribbon, the ''goruem'' (an extending ribbon tied on the right side) instead of the ''twii'' (i.e. the early sash-like belt) and the sleeves were curved slightly.{{Citation needed|date=May 2021}} |

||

The cultural exchange was also bilateral and Goryeo had cultural influence on the [[Mongols]] court of the [[Yuan dynasty]] (1279–1368); one example is the influence of Goryeo women's hanbok on the attire of aristocrats, queens, and concubines of the Mongol court which occurred in the capital city, [[Beijing|Dadu]].<ref>Kim, Ki Sun, 2005. v. 5, 81-97.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=001&oid=028&aid=0000100944&|title=News.Naver.com|access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www1.chinaculture.org/library/2008-01/28/content_28414.htm|title=ChinaCulture.org|access-date=8 October 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141124213026/http://www.chinaculture.org/library/2008-01/28/content_28414.htm|archive-date=24 November 2014}}</ref> However, this influence on the Mongol court clothing mainly occurred in the last years of the Yuan dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Yang|first=Shaorong|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nx5JDiacrH4C&q=korea&pg=PA16|title=Traditional Chinese Clothing: Costumes, Adornments & Culture|date=2004|publisher=Long River Press|isbn=978-1-59265-019-4|page=6}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last1=Kim|first1=Jinyoung|last2=Lee|first2=Jaeyeong|last3=Lee|first3=Jongoh|date=2015|title="GORYEOYANG" AND "MONGOLPUNG" in the 13th-14th CENTURIES|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43957480|journal=Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae|volume=68|issue=3|pages=281–292|doi=10.1556/062.2015.68.3.3|jstor=43957480|issn=0001-6446}}</ref> Throughout the Yuan dynasty, many people from Goryeo were forced to move into the Yuan; most of them were ''kongnyo'' (literally translated as "tribute women"), eunuchs, and war prisoners.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Soh|first=Chung-Hee|date=2004|title=Women's Sexual Labor and State in Korean History|url=http://muse.jhu.edu/content/crossref/journals/journal_of_womens_history/v015/15.4soh.html|journal=Journal of Women's History|volume=15|issue=4|pages=170–177|doi=10.1353/jowh.2004.0022|s2cid=144785547|issn=1527-2036}}</ref> About 2000 women from Goryeo were sent to Yuan as ''kongnyo'' against their will.<ref name=":0" /> Although women from Goryeo were considered very beautiful and good servants, most of them lived in unfortunate situations, marked by hard labour and sexual abuse.<ref name=":0" /> However, this fate was not reserved to all of them; and one Goryeo woman became the last Empress of the [[Yuan dynasty]]; this was [[Empress Gi]] who was elevated as empress in 1365.<ref name=":0" /> Most of the cultural influence that Goryeo exerted on the upper class of the Yuan dynasty occurred when [[Empress Gi]] came into power as empress and started to recruit many Goryeo women as court maids.<ref name=":0" /> The influence of Goryeo on the Mongol court's clothing during the Yuan dynasty was dubbed as ''Goryeoyang'' ("the Goryeo style") and was rhapsodized by the Late Yuan dynasty poet, Zhang Xu, in the form of a short [[banbi]] (半臂) with square collar (方領).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Choi|first=Hai-Yaul|date=2007|title=A Study on the Design of Historical Costume for Making Movie & Multimedia -Focused on Rich Women's Costume of Goryeo-Yang and Mongol-Pung in the 13th to 14th Century-|url=http://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200708508472010.page|journal=Journal of the Korean Society of Costume|volume=57|issue=1|pages=176–186|issn=1229-6880}}</ref> However, so far, the modern interpretation on the appearance of Mongol royal women's clothing influenced by Goryeo is based on authors' suggestions.<ref name=":10" /> Similarly, the possibility that remains of g''oryeoyang'' influence on the [[Ming dynasty]] clothing in China is based on speculations and need to be studied further.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Park|first=Hyunhee|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1198087560|title=Soju : a global history|date=2021|isbn=978-1-108-89577-4|location=Cambridge|pages=124–125|oclc=1198087560}}</ref> |

The cultural exchange was also bilateral and Goryeo had cultural influence on the [[Mongols]] court of the [[Yuan dynasty]] (1279–1368); one example is the influence of Goryeo women's hanbok on the attire of aristocrats, queens, and concubines of the Mongol court which occurred in the capital city, [[Beijing|Dadu]].<ref>Kim, Ki Sun, 2005. v. 5, 81-97.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=001&oid=028&aid=0000100944&|title=News.Naver.com|access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www1.chinaculture.org/library/2008-01/28/content_28414.htm|title=ChinaCulture.org|access-date=8 October 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141124213026/http://www.chinaculture.org/library/2008-01/28/content_28414.htm|archive-date=24 November 2014}}</ref> However, this influence on the Mongol court clothing mainly occurred in the last years of the Yuan dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Yang|first=Shaorong|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nx5JDiacrH4C&q=korea&pg=PA16|title=Traditional Chinese Clothing: Costumes, Adornments & Culture|date=2004|publisher=Long River Press|isbn=978-1-59265-019-4|page=6}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last1=Kim|first1=Jinyoung|last2=Lee|first2=Jaeyeong|last3=Lee|first3=Jongoh|date=2015|title="GORYEOYANG" AND "MONGOLPUNG" in the 13th-14th CENTURIES|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43957480|journal=Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae|volume=68|issue=3|pages=281–292|doi=10.1556/062.2015.68.3.3|jstor=43957480|issn=0001-6446}}</ref> Throughout the Yuan dynasty, many people from Goryeo were forced to move into the Yuan; most of them were ''kongnyo'' (literally translated as "tribute women"), eunuchs, and war prisoners.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Soh|first=Chung-Hee|date=2004|title=Women's Sexual Labor and State in Korean History|url=http://muse.jhu.edu/content/crossref/journals/journal_of_womens_history/v015/15.4soh.html|journal=Journal of Women's History|volume=15|issue=4|pages=170–177|doi=10.1353/jowh.2004.0022|s2cid=144785547|issn=1527-2036}}</ref> About 2000 women from Goryeo were sent to Yuan as ''kongnyo'' against their will.<ref name=":0" /> Although women from Goryeo were considered very beautiful and good servants, most of them lived in unfortunate situations, marked by hard labour and sexual abuse.<ref name=":0" /> However, this fate was not reserved to all of them; and one Goryeo woman became the last Empress of the [[Yuan dynasty]]; this was [[Empress Gi]] who was elevated as empress in 1365.<ref name=":0" /> Most of the cultural influence that Goryeo exerted on the upper class of the Yuan dynasty occurred when [[Empress Gi]] came into power as empress and started to recruit many Goryeo women as court maids.<ref name=":0" /> The influence of Goryeo on the Mongol court's clothing during the Yuan dynasty was dubbed as ''Goryeoyang'' ("the Goryeo style") and was rhapsodized by the Late Yuan dynasty poet, Zhang Xu, in the form of a short [[banbi]] (半臂) with square collar (方領).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Choi|first=Hai-Yaul|date=2007|title=A Study on the Design of Historical Costume for Making Movie & Multimedia -Focused on Rich Women's Costume of Goryeo-Yang and Mongol-Pung in the 13th to 14th Century-|url=http://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200708508472010.page|journal=Journal of the Korean Society of Costume|volume=57|issue=1|pages=176–186|issn=1229-6880}}</ref> However, so far, the modern interpretation on the appearance of Mongol royal women's clothing influenced by Goryeo is based on authors' suggestions.<ref name=":10" /> Similarly, the possibility that remains of g''oryeoyang'' influence on the [[Ming dynasty]] clothing in China is based on speculations and need to be studied further.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Park|first=Hyunhee|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1198087560|title=Soju : a global history|date=2021|isbn=978-1-108-89577-4|location=Cambridge|pages=124–125|oclc=1198087560}}</ref> |

||

===Joseon dynasty=== |

===Joseon dynasty=== |

||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

During the Joseon dynasty, the chima or skirt adopted fuller volume, while the jeogori or blouse took more tightened and shortened form, features quite distinct from the hanbok of previous centuries, when ''chima'' was rather slim and ''jeogori'' baggy and long, reaching well below waist level. After the [[Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98)]] or ''Imjin War'', economic hardship on the peninsula may have influenced the closer-fitting styles that use less fabric.<ref name="Chosun Ilbo2">{{cite news|title=Five Centuries of Shrinking Korean Fashions|newspaper=Chosun Ilbo|url=http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/05/29/2006052961020.html|access-date=2009-06-27}}</ref> |

During the Joseon dynasty, the chima or skirt adopted fuller volume, while the jeogori or blouse took more tightened and shortened form, features quite distinct from the hanbok of previous centuries, when ''chima'' was rather slim and ''jeogori'' baggy and long, reaching well below waist level. After the [[Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98)]] or ''Imjin War'', economic hardship on the peninsula may have influenced the closer-fitting styles that use less fabric.<ref name="Chosun Ilbo2">{{cite news|title=Five Centuries of Shrinking Korean Fashions|newspaper=Chosun Ilbo|url=http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/05/29/2006052961020.html|access-date=2009-06-27}}</ref> |

||

Early Joseon continued the women's fashion for baggy, loose clothing, such as those seen on the mural from the tomb of Bak Ik (1332–1398).<ref>[http://jikimi.cha.go.kr/english/search_plaza_new/ECulresult_Db_View.jsp?VdkVgwKey=13,04590000,38&queryText=(mural%3Cin%3E%20z_title)%3Cand%3E(V_EYEAR%20%3E=1350)&requery=0 Miryang gobeomni bagik byeokhwamyo (Mural tomb of Bak Ik in Gobeop-ri, Miryang)]. [[Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea|Cultural Heritage Administration]]. Accessed 15 July 2009.</ref> |

Early Joseon continued the women's fashion for baggy, loose clothing, such as those seen on the mural from the tomb of Bak Ik (1332–1398).<ref>[http://jikimi.cha.go.kr/english/search_plaza_new/ECulresult_Db_View.jsp?VdkVgwKey=13,04590000,38&queryText=(mural%3Cin%3E%20z_title)%3Cand%3E(V_EYEAR%20%3E=1350)&requery=0 Miryang gobeomni bagik byeokhwamyo (Mural tomb of Bak Ik in Gobeop-ri, Miryang)]. [[Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea|Cultural Heritage Administration]]. Accessed 15 July 2009.</ref> |

||

In the 15th century, neo-confucianism was very rooted in the social life in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries which lead to the strict regulation of clothing (including fabric use, colours of fabric, motifs, and ornaments) based on status.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8bTzilz1BMC&q=Silla+hanbok&pg=PA222|title=The Greenwood encyclopedia of clothing through world history|date=2008|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-33662-1|location=Westport, Connecticut|pages=222–223|oclc=156808055}}</ref> Neo-confucianism also influence women's wearing of full-pleated chima, longer jeogori, and multiple layers clothing in order to never reveal skin.<ref name=":11">{{Cite web|title=Dress - Korea|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/dress-clothing|url-status=live|access-date=2021-03-10|website=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref> The 15th century AD ''chima-jeogori'' style was undoubtedly a clothing style introduced from China.<ref name=":11" /> The women of the upper classes, the monarchy and the court wore hanbok which was inspired by the [[Ming dynasty]] clothing while simultaneously maintaining a distinctive Korean-style look; in turn, the women of the lower class generally imitated the upper class women clothing.<ref name=":12">{{Cite book|last=Welters|first=Linda|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1004424828|title=Fashion history : a global view|date=2018|others=Abby Lillethun|isbn=978-1-4742-5363-5|location=London, UK|oclc=1004424828}}</ref><gallery> |

In the 15th century, neo-confucianism was very rooted in the social life in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries which lead to the strict regulation of clothing (including fabric use, colours of fabric, motifs, and ornaments) based on status.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8bTzilz1BMC&q=Silla+hanbok&pg=PA222|title=The Greenwood encyclopedia of clothing through world history|date=2008|others=Jill Condra|isbn=978-0-313-33662-1|location=Westport, Connecticut|pages=222–223|oclc=156808055}}</ref> Neo-confucianism also influence women's wearing of full-pleated chima, longer jeogori, and multiple layers clothing in order to never reveal skin.<ref name=":11">{{Cite web|title=Dress - Korea|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/dress-clothing|url-status=live|access-date=2021-03-10|website=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref> The 15th century AD ''chima-jeogori'' style was undoubtedly a clothing style introduced from China.<ref name=":11" /> The women of the upper classes, the monarchy and the court wore hanbok which was inspired by the [[Ming dynasty]] clothing while simultaneously maintaining a distinctive Korean-style look; in turn, the women of the lower class generally imitated the upper class women clothing.<ref name=":12">{{Cite book|last=Welters|first=Linda|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1004424828|title=Fashion history : a global view|date=2018|others=Abby Lillethun|isbn=978-1-4742-5363-5|location=London, UK|oclc=1004424828}}</ref><gallery> |

||

File:영의정하연부부영정4.jpg|15th century lady |

File:영의정하연부부영정4.jpg|15th century lady |

||

File:영의정하연부부영정2.jpg|15th century lady |

File:영의정하연부부영정2.jpg|15th century lady |

||

</gallery>However, by the 16th century, the jeogori had shortened to the waist and appears to have become closer fitting, although not to the extremes of the bell-shaped silhouette of the 18th and 19th centuries.<ref>Keum, Ki-Suk "The Beauty of Korean Traditional Costume" (Seoul: Yeorhwadang, 1994) {{ISBN|89-301-1039-8}} p.43</ref><ref name="Contemporary Artwork of Women2">{{cite web|title=Contemporary Artwork of Korean Women|url=http://medieval-baltic.us/korot2.html|access-date=2009-06-27}}</ref><ref name="Chosun Ilbo2" /> In the 16th century, women's [[jeogori]] was long, wide, and covered the waist.<ref name="저고리2">{{cite web|last1=허윤희|title=조선 여인 저고리 길이 300년간 2/3나 짧아져|url=http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2011/06/27/2011062702249.html|access-date=6 September 2019|website=조선닷컴|language=ko}}</ref> The length of women's jeogori gradually shortened: it was approximately 65 cm in the 16th century, 55 cm in the 17th century, 45 cm in the 18th century, and 28 cm in the 19th century, with some as short as 14.5 cm.<ref name="저고리2" /> A heoritti (허리띠) or jorinmal (졸잇말) was worn to cover the breasts.<ref name="저고리2" /> The trend of wearing a short jeogori with a heoritti was started by the [[gisaeng]] and soon spread to women of the upper class.<ref name="저고리2" /> Women of lower class status were however ambivalent towards skin exposure of breasts.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book|last=Lee|first=Samuel Songhoon|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/944510449|title=Hanbok : Timeless fashion tradition|date=2013|others=Han'guk Kukche Kyoryu Chaedan|isbn=978-1-62412-056-5|location=Seoul, Korea|oclc=944510449}}</ref> Among women of the common and lowborn classes, a practice emerged in which they [[Toplessness|revealed their breasts]] by removing a cloth to make breastfeeding more convenient.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Han|first1=Hee-sook|date=2004|title=Women's Life during the Chosŏn Dynasty|url=https://ijkh.khistory.org/journal/view.php?number=342|journal=International Journal of Korean History|volume=6|issue=1|page=142|access-date=6 September 2019}}</ref> The ''breast-exposing hanbok'' was worn with pride as a status symbol in order to show off that they had given birth to a son and to feed her child to make other women envious; at those times, giving birth to a son was the greatest pride of a woman due to the excessive preference for male heirs in [[Joseon]].<ref name=":5" /> |

</gallery>However, by the 16th century, the jeogori had shortened to the waist and appears to have become closer fitting, although not to the extremes of the bell-shaped silhouette of the 18th and 19th centuries.<ref>Keum, Ki-Suk "The Beauty of Korean Traditional Costume" (Seoul: Yeorhwadang, 1994) {{ISBN|89-301-1039-8}} p.43</ref><ref name="Contemporary Artwork of Women2">{{cite web|title=Contemporary Artwork of Korean Women|url=http://medieval-baltic.us/korot2.html|access-date=2009-06-27}}</ref><ref name="Chosun Ilbo2" /> In the 16th century, women's [[jeogori]] was long, wide, and covered the waist.<ref name="저고리2">{{cite web|last1=허윤희|title=조선 여인 저고리 길이 300년간 2/3나 짧아져|url=http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2011/06/27/2011062702249.html|access-date=6 September 2019|website=조선닷컴|language=ko}}</ref> The length of women's jeogori gradually shortened: it was approximately 65 cm in the 16th century, 55 cm in the 17th century, 45 cm in the 18th century, and 28 cm in the 19th century, with some as short as 14.5 cm.<ref name="저고리2" /> A heoritti (허리띠) or jorinmal (졸잇말) was worn to cover the breasts.<ref name="저고리2" /> The trend of wearing a short jeogori with a heoritti was started by the [[gisaeng]] and soon spread to women of the upper class.<ref name="저고리2" /> Women of lower class status were however ambivalent towards skin exposure of breasts.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book|last=Lee|first=Samuel Songhoon|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/944510449|title=Hanbok : Timeless fashion tradition|date=2013|others=Han'guk Kukche Kyoryu Chaedan|isbn=978-1-62412-056-5|location=Seoul, Korea|oclc=944510449}}</ref> Among women of the common and lowborn classes, a practice emerged in which they [[Toplessness|revealed their breasts]] by removing a cloth to make breastfeeding more convenient.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Han|first1=Hee-sook|date=2004|title=Women's Life during the Chosŏn Dynasty|url=https://ijkh.khistory.org/journal/view.php?number=342|journal=International Journal of Korean History|volume=6|issue=1|page=142|access-date=6 September 2019}}</ref> The ''breast-exposing hanbok'' was worn with pride as a status symbol in order to show off that they had given birth to a son and to feed her child to make other women envious; at those times, giving birth to a son was the greatest pride of a woman due to the excessive preference for male heirs in [[Joseon]].<ref name=":5" /> |

||

In the eighteenth century, the ''jeogori'' became very short to the point that the waistband of the ''chima'' was visible; this style was first seen on female entertainers at the Joseon court.<ref name=":12" /> The ''jeogori'' continued to shorten until it reached the modern times ''jeogori''-length; i.e. just covering the breasts.<ref name=":11" /> During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the fullness of the skirt was concentrated around the hips, thus forming a silhouette similar to Western bustles. The fullness of the skirt reached its extreme around 1800. During the 19th century fullness of the skirt was achieved around the knees and ankles thus giving ''chima'' a triangular or an A-shaped silhouette, which is still the preferred style to this day. Many [[Sokgot|undergarments]] such as ''darisokgot,'' ''soksokgot,'' ''dansokgot'', and ''gojengi'' were worn underneath to achieve desired forms. |

In the eighteenth century, the ''jeogori'' became very short to the point that the waistband of the ''chima'' was visible; this style was first seen on female entertainers at the Joseon court.<ref name=":12" /> The ''jeogori'' continued to shorten until it reached the modern times ''jeogori''-length; i.e. just covering the breasts.<ref name=":11" /> During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the fullness of the skirt was concentrated around the hips, thus forming a silhouette similar to Western bustles. The fullness of the skirt reached its extreme around 1800. During the 19th century fullness of the skirt was achieved around the knees and ankles thus giving ''chima'' a triangular or an A-shaped silhouette, which is still the preferred style to this day. Many [[Sokgot|undergarments]] such as ''darisokgot,'' ''soksokgot,'' ''dansokgot'', and ''gojengi'' were worn underneath to achieve desired forms. |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

In contrast, men's lengthy outwear, the equivalent of the modern overcoat, underwent a dramatic change. Before the late 19th century, ''yangban'' men almost always wore ''jungchimak'' when traveling. ''Jungchimak'' had very lengthy sleeves, and its lower part had splits on both sides and occasionally on the back so as to create a fluttering effect in motion. To some this was fashionable, but to others, namely stoic scholars, it was nothing but pure vanity. Daewon-gun successfully banned ''jungchimak'' as a part of his clothes reformation program and ''jungchimak'' eventually disappeared. |

In contrast, men's lengthy outwear, the equivalent of the modern overcoat, underwent a dramatic change. Before the late 19th century, ''yangban'' men almost always wore ''jungchimak'' when traveling. ''Jungchimak'' had very lengthy sleeves, and its lower part had splits on both sides and occasionally on the back so as to create a fluttering effect in motion. To some this was fashionable, but to others, namely stoic scholars, it was nothing but pure vanity. Daewon-gun successfully banned ''jungchimak'' as a part of his clothes reformation program and ''jungchimak'' eventually disappeared. |

||

''[[Durumagi]]'', which was previously worn underneath ''jungchimak'' and was basically a house dress, replaced ''jungchimak'' as the formal outwear for ''yangban'' men. ''Durumagi'' differs from its predecessor in that it has tighter sleeves and does not have splits on either sides or back. It is also slightly shorter in length. Men's hanbok has remained relatively the same since the adoption of ''durumagi''. In 1884, the Gapsin Dress Reform took place.<ref name=":13">{{Cite book|last1=Pyun|first1=Kyunghee|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ivZ0DwAAQBAJ&q=myeonbok&pg=PA55|title=Fashion, identity, and power in modern Asia|last2=Wong|first2=Aida Yuen|date=2018|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-97199-5|location=Cham, Switzerland|oclc=1059514121}}</ref> Under the 1884's decree of [[Gojong of Korea|King Gojong]], only narrow-sleeves traditional overcoat were permitted; as such, all Koreans, regardless of their social class, their age and their gender started to wear the [[durumagi]] or ''chaksuui'' or ''ju-ui'' (周衣).<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":13" /> |

''[[Durumagi]]'', which was previously worn underneath ''jungchimak'' and was basically a house dress, replaced ''jungchimak'' as the formal outwear for ''yangban'' men. ''Durumagi'' differs from its predecessor in that it has tighter sleeves and does not have splits on either sides or back. It is also slightly shorter in length. Men's hanbok has remained relatively the same since the adoption of ''durumagi''. In 1884, the Gapsin Dress Reform took place.<ref name=":13">{{Cite book|last1=Pyun|first1=Kyunghee|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ivZ0DwAAQBAJ&q=myeonbok&pg=PA55|title=Fashion, identity, and power in modern Asia|last2=Wong|first2=Aida Yuen|date=2018|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-319-97199-5|location=Cham, Switzerland|oclc=1059514121}}</ref> Under the 1884's decree of [[Gojong of Korea|King Gojong]], only narrow-sleeves traditional overcoat were permitted; as such, all Koreans, regardless of their social class, their age and their gender started to wear the [[durumagi]] or ''chaksuui'' or ''ju-ui'' (周衣).<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":13" /> |

||

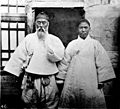

Hats was an essential part formal dress and the development of official hats became even more pronounced during this era due to the emphasis of Confucian values.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book|last=Ch'oe|first=Ŭn-su|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/846696816|title=Gat : traditional headgear in Korea|date=2012|others=Hyŏng-bak Pak, Eunhee Hwang, Kungnip Munhwajae Yŏn'guso|isbn=978-89-6325-987-1|location=Daejeon, Korea|oclc=846696816}}</ref> The [[Gat (hat)|gat]] was considered an essential aspect in a man's life; however, to replace the gat in more informal setting, such as their residences, and to feel more comfortable, Joseon-era aristocrats also adopted a lot hats which were introduced from China, such as the banggwan, sabanggwan, dongpagwan, waryonggwan, jeongjagwan.<ref name=":6" /> The popularity of those Chinese hats may have partially been due to the promulgation of Confucianism and because they were used by literary figures and scholars in China.<ref name=":6" /> In 1895, King Gojong decreed adult Korean men to cut their hair short and western-style clothing were allowed and adopted.<ref name=":13" /><gallery> |

Hats was an essential part formal dress and the development of official hats became even more pronounced during this era due to the emphasis of Confucian values.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book|last=Ch'oe|first=Ŭn-su|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/846696816|title=Gat : traditional headgear in Korea|date=2012|others=Hyŏng-bak Pak, Eunhee Hwang, Kungnip Munhwajae Yŏn'guso|isbn=978-89-6325-987-1|location=Daejeon, Korea|oclc=846696816}}</ref> The [[Gat (hat)|gat]] was considered an essential aspect in a man's life; however, to replace the gat in more informal setting, such as their residences, and to feel more comfortable, Joseon-era aristocrats also adopted a lot hats which were introduced from China, such as the banggwan, sabanggwan, dongpagwan, waryonggwan, jeongjagwan.<ref name=":6" /> The popularity of those Chinese hats may have partially been due to the promulgation of Confucianism and because they were used by literary figures and scholars in China.<ref name=":6" /> In 1895, King Gojong decreed adult Korean men to cut their hair short and western-style clothing were allowed and adopted.<ref name=":13" /><gallery> |

||

| Line 197: | Line 197: | ||

Before the 19th century, women of high social backgrounds and ''[[gisaeng]]'' wore wigs (''[[gache]]''). Like their Western counterparts, Koreans considered bigger and heavier wigs to be more desirable and aesthetic. Such was the women's frenzy for the ''gache'' that in 1788 [[Jeongjo of Joseon|King Jeongjo]] banned by royal decree the use of ''gache'', as they were deemed contrary to the [[Korean Confucianism|Korean Confucian]] values of reserve and restraint.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Traditional Art of Beauty and Perfume in Ancient Korea {Cultural Notes} {Beauty Notes} - The Scented Salamander: Perfume & Beauty Blog & Webzine|url=http://www.mimifroufrou.com/scentedsalamander/2008/04/beauty_perfume_in_traditional.html|website=www.mimifroufrou.com}}</ref> |

Before the 19th century, women of high social backgrounds and ''[[gisaeng]]'' wore wigs (''[[gache]]''). Like their Western counterparts, Koreans considered bigger and heavier wigs to be more desirable and aesthetic. Such was the women's frenzy for the ''gache'' that in 1788 [[Jeongjo of Joseon|King Jeongjo]] banned by royal decree the use of ''gache'', as they were deemed contrary to the [[Korean Confucianism|Korean Confucian]] values of reserve and restraint.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Traditional Art of Beauty and Perfume in Ancient Korea {Cultural Notes} {Beauty Notes} - The Scented Salamander: Perfume & Beauty Blog & Webzine|url=http://www.mimifroufrou.com/scentedsalamander/2008/04/beauty_perfume_in_traditional.html|website=www.mimifroufrou.com}}</ref> |

||

Due to the influence of Neo-Confucianism, it was compulsory for women throughout the entire society to wear headdresses (''nae-oe-seugae'') to avoid exposing their faces when going outside; those headdresses may include ''suegaechima'' (a headdress which looked like a ''chima'' but was narrower and shorter in style worn by the upper class women and later by all classes of people in late Joseon), the [[jang-ot]], and the ''neoul'' (which was only permitted for court ladies and noblewomen).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cho|first=Seunghye|date=2017-09-03|title=The Ideology of Korean Women's Headdresses during the Chosŏn Dynasty|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2016.1251089|journal=Fashion Theory|volume=21|issue=5|pages=553–571|doi=10.1080/1362704X.2016.1251089|s2cid=165117375|issn=1362-704X}}</ref> |

Due to the influence of Neo-Confucianism, it was compulsory for women throughout the entire society to wear headdresses (''nae-oe-seugae'') to avoid exposing their faces when going outside; those headdresses may include ''suegaechima'' (a headdress which looked like a ''chima'' but was narrower and shorter in style worn by the upper class women and later by all classes of people in late Joseon), the [[jang-ot]], and the ''neoul'' (which was only permitted for court ladies and noblewomen).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cho|first=Seunghye|date=2017-09-03|title=The Ideology of Korean Women's Headdresses during the Chosŏn Dynasty|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2016.1251089|journal=Fashion Theory|volume=21|issue=5|pages=553–571|doi=10.1080/1362704X.2016.1251089|s2cid=165117375|issn=1362-704X}}</ref> |

||

In the 19th century ''yangban'' women began to wear ''jokduri'', a small hat that replaced ''gache''. However ''gache'' enjoyed vast popularity in ''kisaeng'' circles well into the end of the century. |

In the 19th century ''yangban'' women began to wear ''jokduri'', a small hat that replaced ''gache''. However ''gache'' enjoyed vast popularity in ''kisaeng'' circles well into the end of the century. |

||

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

<!-- [[File:Wonsam.jpg|thumb|left|[[Wonsam]], 원삼]] --> |

<!-- [[File:Wonsam.jpg|thumb|left|[[Wonsam]], 원삼]] --> |

||

'''''[[Wonsam]]''''' (Hangul: 원삼) was a ceremonial overcoat for a married woman in the [[Joseon]] dynasty.<ref name= "Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)">Cho, Eun-ah, [http://cnews041.com/sub_read.html?uid=46289§ion=sc151 "Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)"], "C News041", 2012/11/12</ref> The [[Wonsam]] was also adopted from [[China]] and is believed to have been one of the costumes from the [[Tang dynasty]] which was bestowed in the Unified Three Kingdoms period.<ref name=":1"/> It was mostly worn by royalty, high-ranking court ladies, and noblewomen and the colors and patterns represented the various elements of the Korean class system.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> The empress wore yellow; the queen wore red; the crown princess wore a purple-red color; meanwhile a princess, a king's daughter by a [[concubine]], and a woman of a noble family or lower wore green.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> All the upper social ranks usually had two colored stripes in each sleeve: yellow-colored Wonsam usually had red and blue colored stripes, red-colored Wonsam had blue and yellow stripes, and green-colored Wonsam had red and yellow stripes.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> Lower-class women wore many accompanying colored stripes and ribbons, but all women usually completed their outfit with '''Onhye''' or '''Danghye''', traditional Korean shoes.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> |

'''''[[Wonsam]]''''' (Hangul: 원삼) was a ceremonial overcoat for a married woman in the [[Joseon]] dynasty.<ref name= "Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)">Cho, Eun-ah, [http://cnews041.com/sub_read.html?uid=46289§ion=sc151 "Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)"], "C News041", 2012/11/12</ref> The [[Wonsam]] was also adopted from [[China]] and is believed to have been one of the costumes from the [[Tang dynasty]] which was bestowed in the Unified Three Kingdoms period.<ref name=":1"/> It was mostly worn by royalty, high-ranking court ladies, and noblewomen and the colors and patterns represented the various elements of the Korean class system.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> The empress wore yellow; the queen wore red; the crown princess wore a purple-red color; meanwhile a princess, a king's daughter by a [[concubine]], and a woman of a noble family or lower wore green.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> All the upper social ranks usually had two colored stripes in each sleeve: yellow-colored Wonsam usually had red and blue colored stripes, red-colored Wonsam had blue and yellow stripes, and green-colored Wonsam had red and yellow stripes.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> Lower-class women wore many accompanying colored stripes and ribbons, but all women usually completed their outfit with '''Onhye''' or '''Danghye''', traditional Korean shoes.<ref name="Cho Eun-ah's Hanbok Story(25)" /> |

||

====Dangui==== |

====Dangui==== |

||

| Line 250: | Line 251: | ||

====Cheolique==== |

====Cheolique==== |

||

'''''[[Terlig|Cheolique]]''''' (Alt. Cheolick or Cheollik) (Hangul: 철릭) was a Korean adaptation of the [[Terlig|Mongol tunic]], imported in the late 1200s during the [[Goryeo dynasty]]. Cheolique, unlike other forms of Korean clothing, is an amalgamation of a blouse with a kilt into a single item of clothing. The flexibility of the clothing allowed easy horsemanship and archery. During the [[Joseon dynasty]], they continued to be worn by the king, and military officials for such activities.<ref name="Cheolique">Encyclopedia of Korean Culture and The Academy of Korean Studies, [http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?cid=1646&docId=563301&categoryId=1646 "Cheolique"], "Naver Knowledge Encyclopedia"</ref> It was usually worn as a military uniform, but by the end of the Joseon dynasty, it had begun to be worn in more casual situations.<ref name="Cheolique" |

'''''[[Terlig|Cheolique]]''''' (Alt. Cheolick or Cheollik) (Hangul: 철릭) was a Korean adaptation of the [[Terlig|Mongol tunic]], imported in the late 1200s during the [[Goryeo dynasty]]. Cheolique, unlike other forms of Korean clothing, is an amalgamation of a blouse with a kilt into a single item of clothing. The flexibility of the clothing allowed easy horsemanship and archery. During the [[Joseon dynasty]], they continued to be worn by the king, and military officials for such activities.<ref name="Cheolique">Encyclopedia of Korean Culture and The Academy of Korean Studies, [http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?cid=1646&docId=563301&categoryId=1646 "Cheolique"], "Naver Knowledge Encyclopedia"</ref> It was usually worn as a military uniform, but by the end of the Joseon dynasty, it had begun to be worn in more casual situations.<ref name="Cheolique"/> A unique characteristic allowed the detachment of the Cheolique's sleeves which could be used as a bandage if the wearer was injured in combat.<ref name="Cheolique" /> |

||

<!-- [[File:Blue Cheolique.jpg|thumb|left|Blue Cheolique for military officials in [[Joseon]] Dynasty]] --> |

<!-- [[File:Blue Cheolique.jpg|thumb|left|Blue Cheolique for military officials in [[Joseon]] Dynasty]] --> |

||

| Line 272: | Line 273: | ||

<!-- [[File:Norigae.jpg|thumb|right|[[Norigae]], 노리개]] --> |

<!-- [[File:Norigae.jpg|thumb|right|[[Norigae]], 노리개]] --> |

||

'''''[[Norigae]]''''' (Hangul: 노리개) was a typical traditional accessory for women; it was worn by all women regardless of social ranks.<ref name="Norigae">Doopedia, [http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?cid=200000000&docId=1076917&categoryId=200000392 "Norigae"], "Naver Knowledge Encyclopedia"</ref><ref name=":14">{{Cite book|last=Yi|first=Kyŏng-ja|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/71358055|title=Norigae : splendor of the Korean Costume|date=2005|publisher=Ewha Womans University Press|others=Lee Jean Young|isbn=89-7300-618-5|location=Seoul, Korea|pages= |

'''''[[Norigae]]''''' (Hangul: 노리개) was a typical traditional accessory for women; it was worn by all women regardless of social ranks.<ref name="Norigae">Doopedia, [http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?cid=200000000&docId=1076917&categoryId=200000392 "Norigae"], "Naver Knowledge Encyclopedia"</ref><ref name=":14">{{Cite book|last=Yi|first=Kyŏng-ja|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/71358055|title=Norigae : splendor of the Korean Costume|date=2005|publisher=Ewha Womans University Press|others=Lee Jean Young|isbn=89-7300-618-5|location=Seoul, Korea|pages=12–13|oclc=71358055}}</ref> However, the social rank of the wearer determined the different sizes and materials of the norigae.<ref name=":14" /> |

||

====Danghye==== |

====Danghye==== |

||

| Line 295: | Line 296: | ||

In Seoul, a tourist's wearing of hanbok makes their visit to the Five Grand Palaces (Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, Gyeongbokgung and Gyeonghuigung) free of charge. |

In Seoul, a tourist's wearing of hanbok makes their visit to the Five Grand Palaces (Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, Gyeongbokgung and Gyeonghuigung) free of charge. |

||

==Recent history== |

|||

=== Controversy over distortion of hanbok in China === |

|||

The controversy over distortion of hanbok in China is a series of moves in China to incorporate Korean traditional clothing, hanbok, into 'Chinese culture, traditional Chinese clothing' and to give it a Chinese identity. It is a kind of attempt by China to subjugate Korean culture. |

|||

Controversy over distortion of hanbok in China has existed since the time of China’s Northeast Asia Project<ref>{{cite web|url=http://korea.prkorea.com/wordpress/english/2012/03/15/dispute-over-history-chinas-northeast-asia-project |script-title=Dispute over history: China’s Northeast Asia Project |publisher=[[VANK]]}}</ref>. Since the 2000s, hanbok has appeared in various Chinese cultural media, including Chinese dramas, and was introduced as a type of hanfu. As a result, disputes began to arise between China and Korea. |

|||

In early November 2020, the Chinese mobile game 'Shining Nikki' changed the hanbok costume that was promoted as a Korean traditional costume to a Chinese traditional costume due to a Chinese user's protest. As Korean users protested, 'Shining Nikki' announced the abrupt termination of the Korean service.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://game.mk.co.kr/view.php?year=2020&no=1140729/|title="한복 동북공정 논란 ‘샤이닝니키’ 1주일만에 서비스 종료"…환불 절차 안내 없어 또 ‘논란’|trans-title="Shining Nikki's service ended after 1 week of controversy over the Hanbok Northeast Project" No refund procedure, another ‘controversy’ |publisher=Maeil Business Newspaper|date=November 6, 2020|language=ko}}</ref> Through this 'Shining Nikki' Hanbok incident, the controversy about the distortion of Hanbok and Hanfu in China directly occurred in Korea. Koreans began to perceive China's Northeast Project for Hanbok as a serious problem, calling it the 'Hanbok Northeast Project'. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 318: | Line 328: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*{{Commons category-inline}} |

|||

*{{Commonscatinline}} |

|||

* [https://thekoreaninme.com/blogs/hanbok-philosophy/hanbok-history-evolution Hanbok History Evolution] |

* [https://thekoreaninme.com/blogs/hanbok-philosophy/hanbok-history-evolution Hanbok History Evolution] |

||

* [https://thekoreaninme.com/blogs/hanbok-philosophy/hanbok-history-infographic Hanbok History Infographic] |

* [https://thekoreaninme.com/blogs/hanbok-philosophy/hanbok-history-infographic Hanbok History Infographic] |

||

Revision as of 08:25, 16 July 2021

| Traditional Korean dress | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 한복 | ||||||

| Hanja | 韓服 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 조선옷 | ||||||

| Hanja | 朝鮮옷 | ||||||

| |||||||

The hanbok (in South Korea) or Chosŏn-ot (in North Korea) is the traditional Korean clothes. The term "Hanbok" literally means "Korean clothing". It was established as a part of the unique living culture of Korea, influenced by the geographical and climatic nature of the Korea, and handed down throughout the years to present times.[1]

Hanbok is characterized by its wrapped front top, long, high waisted skirt and its typically vibrant colours. Two piece clothing style of Hanbok is closer to the style of the nomadic tribes.[2]

Hanbok can be traced back to the Three Kingdoms of Korea period (1st century BC ~ 7th century AD), with roots in the peoples of what is now northern Korea and Manchuria. Early forms of Hanbok can be seen in the art of Goguryeo tomb murals in the same period. The earliest ones can be found in mural paintings dating from the 5th century.[3] From this time, the basic structure of hanbok, namely the jeogori jacket, baji pants, and the chima skirt, were already established. Short, tight trousers and tight, waist-length jackets were worn by both men and women during the early years of the Three Kingdoms of Korea period. The basic structure and these basic design features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day.

In the modern day, "hanbok" usually refers specifically to the clothing worn and developed during the Joseon dynasty period by the upper classes. In general, the clothing of Korea's rulers and aristocrats was influenced by both foreign and indigenous styles, resulting in some styles of clothing, such as the simui from China's Song Dynasty, gwanbok worn by male officials and Court clothing of women in the court and women of royalty were adapted from the clothing style of China's Ming dynasties.[4][5] The cultural exchange was also bilateral and Goryeo hanbok had cultural influence on the Yuan dynasty.[6] The commoners were less influenced by those foreign fashion trend, and they mainly wore a style of indigenous clothing distinct from that of the upper classes.[7]

Koreans wear Hanbok for formal or semi-formal occasions and events such as festivals, celebrations, and ceremonies. In 1996, the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism established "Hanbok Day" to encourage South Korean citizens to wear the hanbok.[8]

Construction and design

1. hwajang

2. godae

3. somae buri

4. somae

5. goreum

6. u

7. doryeon

8, 11. jindong

9. gil

10. baerae

12. git

13. dongjeong

Traditionally, women's hanbok consist of the jeogori (a blouse shirt or a jacket) and the chima (a full, wrap around skirt). The ensemble is often known as chima jeogori. Men's hanbok consist of jeogori and loose fitting baji (trousers).[9]

Jeogori

Jeogori is the basic upper garment of the hanbok, worn by both men and women. It covers the arms and upper part of the wearer's body.[10][11] The basic form of a jeogori consists of gil, git, dongjeong, goreum and sleeves. Gil (Hangul: 길) is the large section of the garment on both front and back sides, and git (Hangul: 깃) is a band of fabric that trims the collar. Dongjeong (Hangul: 동정) is a removable white collar placed over the end of the git and is generally squared off. The goreum (Hangul: 고름) are coat-strings that tie the jeogori.[9] Women's jeogori may have kkeutdong (Hangul: 끝동), a different colored cuff placed at the end of the sleeves. Two jeogori may be the earliest surviving archaeological finds of their kind. One from a Yangcheon Heo clan tomb is dated 1400–1450,[12] while the other was discovered inside a statue of the Buddha at Sangwonsa Temple (presumably left as an offering) that has been dated to the 1460s.[13]

The form of Jeogori has changed over time.[14] While men's jeogori remained relatively unchanged, women's jeogori dramatically shortened during the Joseon dynasty, reaching its shortest length at the late 19th century. However, due to reformation efforts and practical reasons, modern jeogori for women is longer than its earlier counterpart. Nonetheless the length is still above the waistline. Traditionally, goreum were short and narrow, however modern goreum are rather long and wide. There are several types of jeogori varying in fabric, sewing technique, and shape.[14][12]

Chima

Chima refers to "skirt," which is also called sang (裳) or gun (裙) in hanja.[15][10][14] The underskirt, or petticoat layer, is called sokchima. According to ancient murals of Goguryeo and an earthen toy excavated from the neighborhood of Hwangnam-dong, Gyeongju, Goguryeo women wore a chima with jeogori over it, covering the belt.[16][17]

Although striped, patchwork, and gored skirts are known from the Goguryeo[10] and Joseon periods, chima were typically made from rectangular cloth that was pleated or gathered into a skirt band.[18] This waistband extended past the skirt fabric itself and formed ties for fastening the skirt around the body.[19]

Sokchima was largely made in a similar way to the overskirts until the early 20th century when straps were added,[20] later developing into a sleeveless bodice or 'reformed' petticoat.[21] By the mid-20th century, some outer chima had also gained a sleeveless bodice, which was then covered by the jeogori.[22][23]

Baji

Baji refers to the bottom part of the men's hanbok. It is the formal term for 'trousers' in Korean. Compared to western style pants, it does not fit tightly. The roomy design is aimed at making the clothing ideal for sitting on the floor.[24] It functions as modern trousers do, but nowadays the term baji is commonly used in Korea for any kinds of pants. There is a band around the waistline of a baji for tying in order to fasten.

Baji can be unlined trousers, leather trousers, silk pants, or cotton pants, depending on style of dress, sewing method, embroidery and so on.

Po